The recent Supreme Court decisions of Hollingsworth v. Perry, which struck down California’s ban on gay marriage under Proposition 8, and United States v. Windsor, which invalidated the Defense of Marriage Act, have heightened public discussion of Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual and Transgender (LGBT) issues. Such rulings, along with a majority of Americans now support legalizing gay marriage, are seen as a sort of light at the end of the tunnel in the pursuit of legal and marriage equality for the gay community.

These events should undoubtedly be celebrated, but the true victory for the gay rights movement lies in the acceptance by the public as a whole. It is unclear when marriage equality will be fully realized, but it is imminent and will be reached before there is a solid consensus, rather than majority, of people who support gay marriage. Until the public more fully embraces gay rights, however, an important way to achieve greater acceptance of marriage equality is to eradicate homophobia – not the attitude, but the word itself.

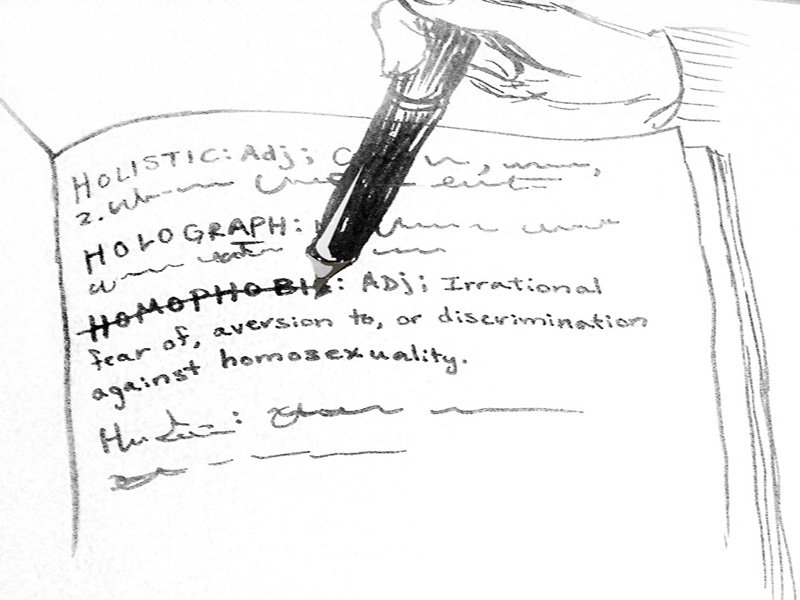

The term “homophobia” was first used by psychologist George Weinberg in the late 1960s. It served an important purpose of identifying negative attitudes or behavior toward homosexuality. It was also the first instance in which anti-gay sentiment was given a label. It was groundbreaking in its attempt to call attention to prejudice and a stigma toward gay people. But the word has long outlived its purpose.

Oftentimes, it is used to describe controversial statements or opinions in the media – a public figure or organization says something prejudiced and the subsequent headline almost always includes some variation of the word “homophobic.”

In fact, there is not a clinical basis for a phobia, or an irrational fear, of homosexuality like there is of heights or spiders. And the word is rarely used in the context of an actual fear. Some people are undoubtedly uncomfortable in the presence of gay people or look unfavorably upon homosexuality, but an irrational fear is absurd. The only common denominator between the denotation of the word and what it intends to represent is irrationality.

According to an April 2012 article in The New York Times titled “Homophobic? Maybe You’re Gay,” there is a correlation between strongly believing that homosexuality is morally wrong and repressing confusion toward one’s own sexual orientation. This confused aversion seems the most apt use of the word “homophobic.”

People often say, “well, I’m homophobic,” to qualify anti-gay prejudice as if they have a condition, which excuses such intolerance. The word is so commonplace in American culture, even among well-intentioned people, that its literal meaning and the context in which it is used are rarely examined.

At best, “homophobia” is a misnomer and at worst, it excuses bigotry. At the heart of the problem lies the hypocrisy on which someone vehemently opposes another’s sexual orientation but hides behind a euphemism rather than admitting such intolerance.

Everyone has the right to an opinion and to speak however they choose. Any effort to control how people view a particular issue is usually futile.

This is not a prescription for political correctness or an effort to control speech but rather a call for more honesty with respect to gay-related issues. The word “homophobia” conceals the truth that, despite substantial progress in gay rights in recent years, there is still widespread intolerance toward gay people in society.

So how should such prejudice be labeled while avoiding this euphemism? Simple changes in the identification of behavior usually described as “homophobic” – like instead saying “anti-gay,” “anti-LGBT” or even “prejudiced” and “intolerant” – would add more honesty and accuracy to the discussion.

None of these labels lack the immediate word association or conciseness of the word “homophobia,” but they take the issue for what it is and do not try to excuse intolerance.

As mentioned before, the struggle for gay rights will be won when the public embraces equality between people of different sexual orientations. A shift away from euphemistic language is the first step in asserting that such prejudice should no longer be tolerated or excused in this society.

Online Editor Ross Fogg is a College senior from Fayetteville, Ga.

Cartoon by Katrina Worsham

The Emory Wheel was founded in 1919 and is currently the only independent, student-run newspaper of Emory University. The Wheel publishes weekly on Wednesdays during the academic year, except during University holidays and scheduled publication intermissions.

The Wheel is financially and editorially independent from the University. All of its content is generated by the Wheel’s more than 100 student staff members and contributing writers, and its printing costs are covered by profits from self-generated advertising sales.