Jack Rutherford/Staff Photographer

Danielle LeSure (02C) had never heard of the hammer throw event before college. Today, she holds a 21-year-old program record for the hammer throw at 52.5 meters in addition to eight of the top 10 farthest throws in program history.

Hundreds of athletes across 19 varsity sports have written their names in Emory University’s record books. However, few records have remained unbroken for decades. The Emory Wheel spoke with two long-standing record holders about their journey to Emory and the legacy they have left on the University.

Hammer throw record still unscathed 21 years later

LeSure initially tried out for track and field in high school because everyone was guaranteed a spot on the team. On the first day of practice, she began training for the track events, but almost immediately, her workout morphed from running into jogging and then power walking. Looking for an alternative, LeSure’s high school coaches introduced her to throwing. There, she discovered her love for discus and shotput.

LeSure said she had a great high school career, but Emory’s track and field team did not recruit her. When she arrived on campus, LeSure visited the track and field office to discuss walking on to the team with the coaching staff.

“They were like, ‘You can be a part of the track team, and one day, you’re gonna be up on that wall for a hammer,’” LeSure said. “And I said, ‘What is a hammer?’”

The hammer throw was not allowed at LeSure’s high school because it was deemed too dangerous, but her coaches at Emory told her that since she was explosive with a discus, she could replicate that with a hammer. Although LeSure loved throwing in high school, her first season at Emory was challenging.

“Freshman year was really hard because I’m throwing something I just learned about,” LeSure said. “I’m going around in a circle with a heavy metal ball tied to metal wire and a handle, flying and flying fast — faster than when you have a discus — and you can’t really control it because the way that it flies is taking you as well.”

In order to succeed in the new event, LeSure said she needed to understand the physics behind the hammer throw and develop techniques to visualize her release. Her teammate and thrower Benjamin Kim (01C) helped her learn the biomechanics of turning before a throw during her first indoor track and field season. To prepare for each major throw, LeSure said she did not need music to get hyped up. Instead, she read poetry and played calming music, such as Erykah Badu and “Voodoo” (2000) by D’Angelo, to “get centered” and “imagine” what her throws would feel like.

“It’s not enough to just give it your all during practice. You have to go above and beyond and I think that’s the part that people need to recognize.” – Danielle LeSure (02C)

In addition to being a student-athlete, LeSure said she commuted downtown for internships at the Georgia State Governor’s Office and the Georgia State University Andrew Young School of Policy Studies. LeSure then returned to campus for practice and remained in the throwing circle to work on her turns and footwork “until the lights came on” late at night. Her former throws coach Heather Graham, who joined Emory’s coaching staff during LeSure’s sophomore year, said she even gave LeSure extra reading about the hammer throw to help her improve outside of practice.

“It’s not enough to just give it your all during practice,” LeSure said. “You have to go above and beyond, and I think that’s the part that people need to recognize.”

LeSure also contributed a major part of her success to advocating to her coaches for specialized thrower training. Unlike the distance runners and sprinters, the throwers ran football agility drills to improve their footwork. LeSure said speaking up about throwers’ different needs led her into her current career in education advocacy.

“We actually spoke up, and we had a voice,” LeSure said. “It was a voice where we’re different and that’s OK.”

With the right resources and many extra hours of training, LeSure thrived in the hammer and weight throw events. She won five University Athletic Association (UAA) titles and back-to-back national hammer throw titles at the 2001 and 2oo2 NCAA Division III Outdoor Track and Field Championships, the latter of which earned her the Emory record.

Graham said her reaction to LeSure’s record-breaking throw has stuck with her after all these years.

“As a coach, you know and you can tell,” Graham said. “You can look at their footwork … and you just hope when they release, they’re going to stand up with all their might and extend their hands, their arms, and she did. I just knew the ball was going to go flying that day. When they said the mark, I just couldn’t believe it.”

LeSure referred to her legacy on Emory sports as “one of resilience.” The track team did not recruit her, but LeSure achieved unprecedented success and a feature on the George W. Woodruff Physical Education Center’s Hall of Fame wall, fulfilling the prediction her Emory coaches made at the beginning of her collegiate career.

“Her impact on Emory sports shined a light on the field part of track and field,” Graham said. “Everyone always forgets about the field portion … Now she has made the throwing part of track and field more recognizable, especially because [the University] used an image of her throwing on the Hall of Fame wall.”

Two-time national hammer throw champion Danielle Lesure (02C) receives a ring during Emory’s 2023 Hall of Fame Induction Ceremony on Oct. 21. (Natalie Sandlow/Staff Photographer)

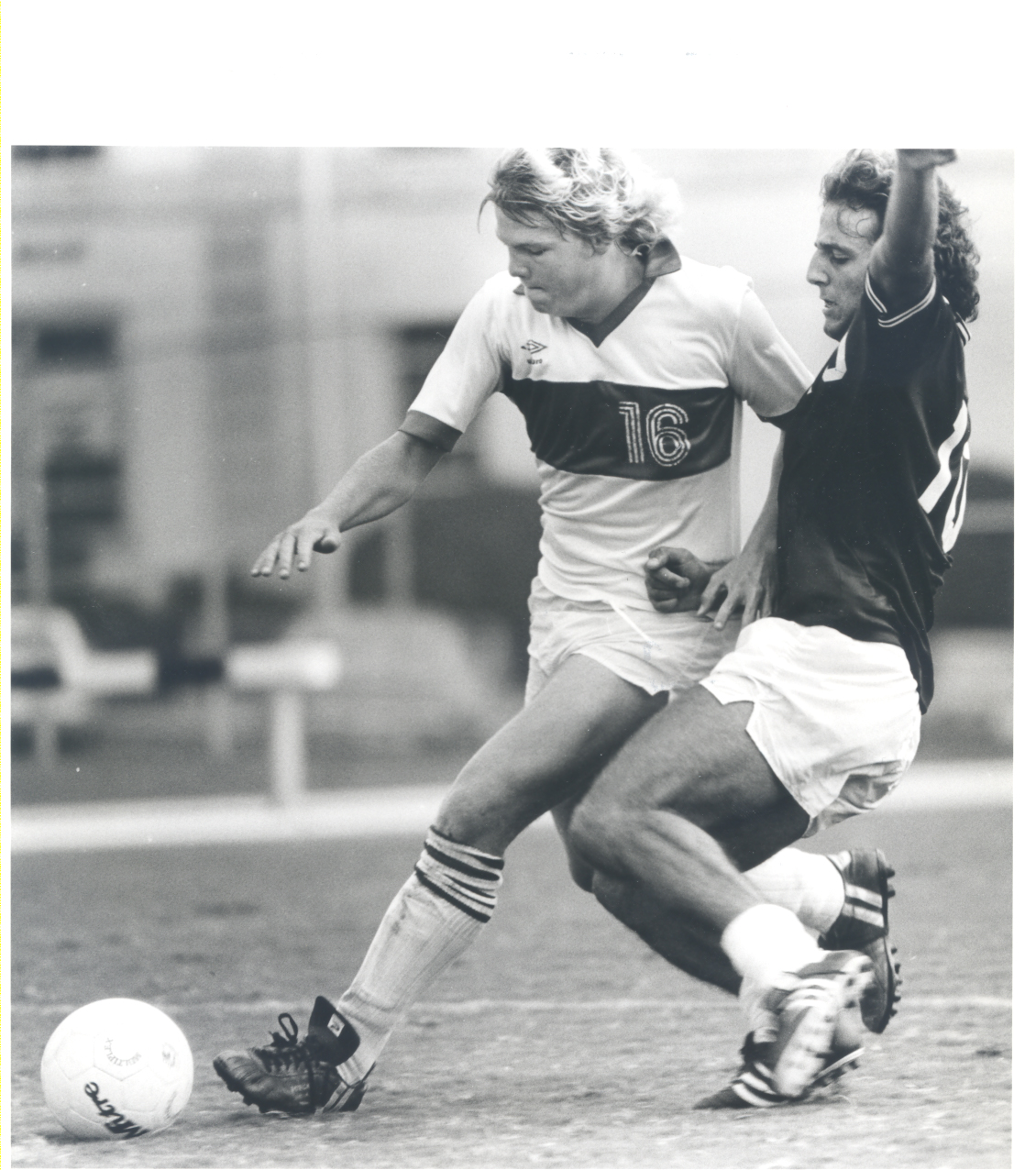

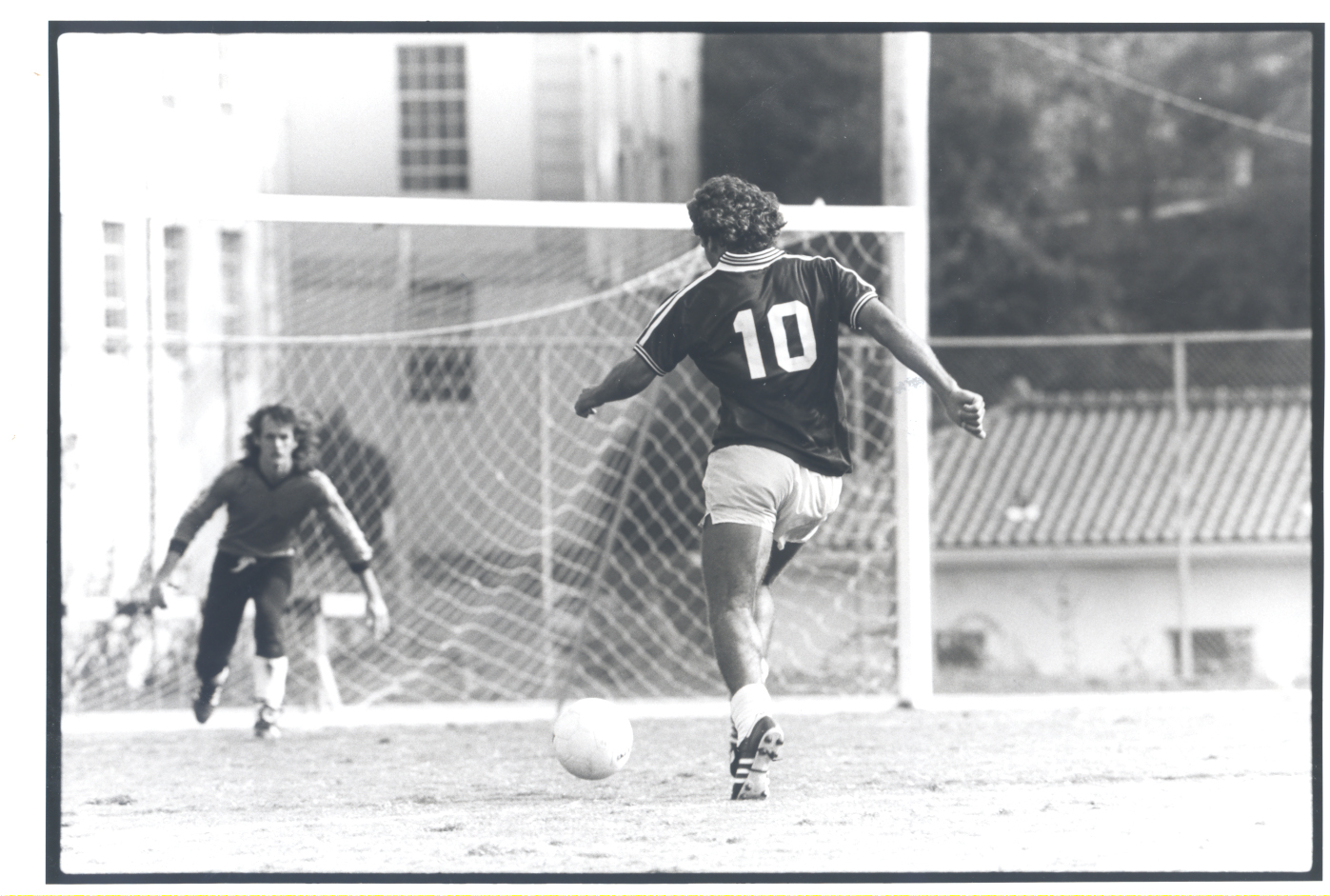

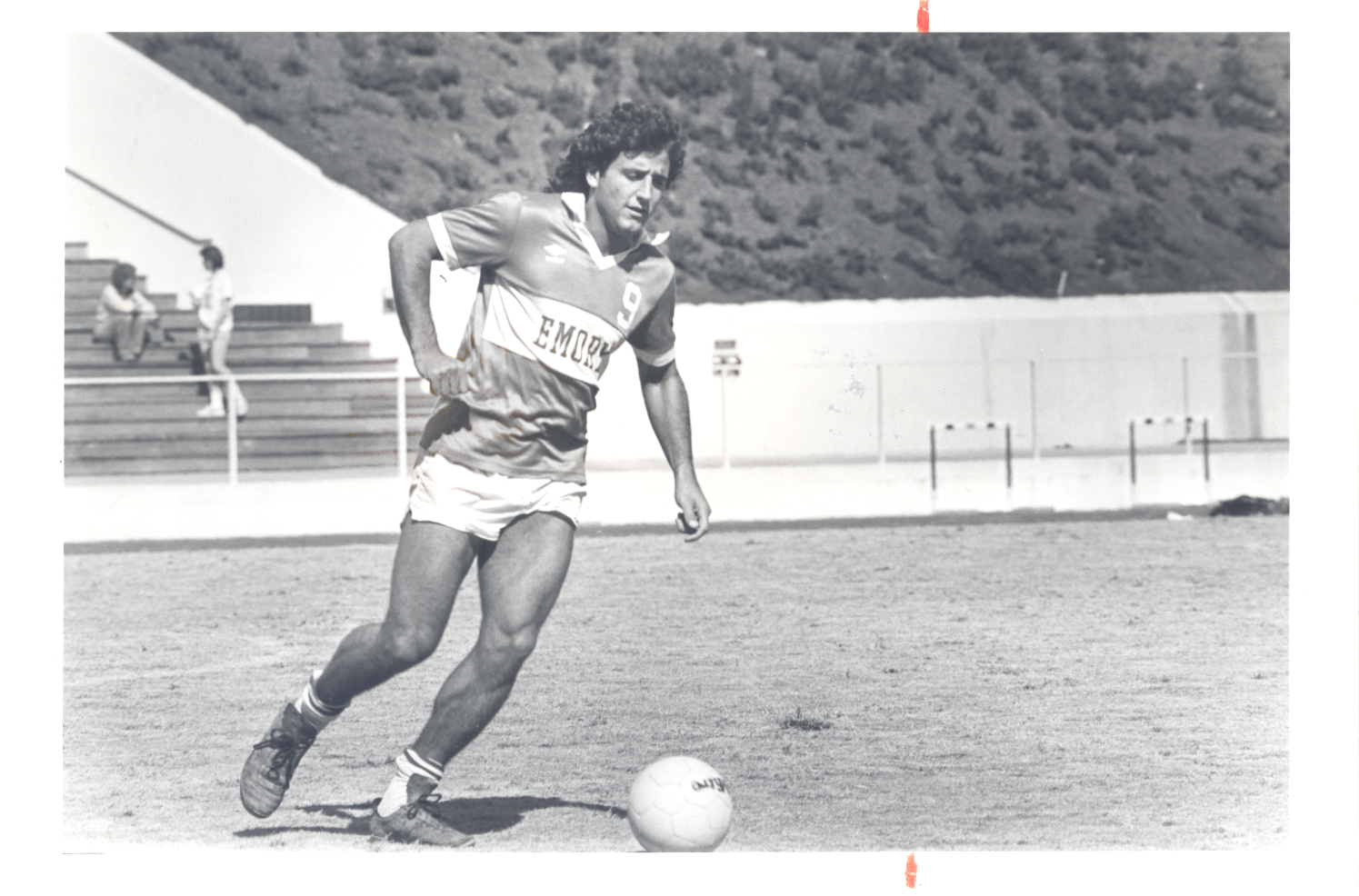

Emory men’s soccer goals record remains unbroken for 39 years

Derrick Beare (82Ox, 84B), another Emory Hall of Fame inductee, also has a lasting legacy in Emory athletics. His men’s soccer record of 25 goals in a single season has remained standing for nearly 40 years.

The South-African-born striker was finishing his secondary school in London when he received a call from former Oxford College Men’s Soccer Head Coach Richard Chappell to join the team for two years. During his time at Oxford, the team was nationally ranked and featured players from “all over the world,” he said.

Derrick Beare originally planned to transfer to the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill for soccer after Oxford, but former Emory Men’s Soccer Head Coach Thomas Johnson (64G) encouraged him to stay at Emory to play for the Atlanta team. Derrick Beare said he had more fun and made more lasting connections playing on the Atlanta team.

“Oxford, I lost touch with all or most of the players,” Derrick Beare said. “But in Emory, I’m still friendly with a few of them.”

He had a successful first year on the Emory team. Derrick Beare scored 19 goals in 1982, tied with Ahmed Mohyeldin (99C) for the fourth-best individual goal scoring season in program history.

However, Derrick Beare’s father passed away at 40 years old before his senior year. During what he said “was a very difficult time” in his life, he put soccer on hold and took a year off from school.

When he returned to the team in the fall of 1984, he said the whole team rallied around him, forming a “very strong bond.” He credited this supportive atmosphere to his incredible run that year, scoring 25 goals and providing 14 assists in a 21-game season.

His contributions and teammate Boris Jerkunica’s (85C, 87G) 17 goals helped the team win 16 games and reach the Round of 24 in the NCAA Division III Men’s Soccer Tournament. Derrick Beare joked that his teammates “loved” him during that record-breaking season.

Although he only played two seasons at Emory, his 44 career goals rank fifth for the most in program history. He received a Division III First Team All-America Honor in 1984, which only four Emory men’s soccer players have achieved.

“I think I brought focus to sports [at Emory],” Derrick Beare said. “When I was at Emory, it was only soccer, really. I definitely built the profile of the college because it’s the best we ever did, and I was one of the better players that Emory’s had.”

Derrick Beare’s Emory soccer legacy runs deeper than long-standing records. His son Joe Beare is currently a fifth-year student and captain of the Emory men’s soccer team.

Joe Beare had a strong start to his freshman year, scoring a few goals, but he said the COVID-19 pandemic disrupted his sophomore season. Last year, the team finished seventh in the UAA conference standings and missed out on the national tournament, but they hope to “change the culture” this season.

This year marks the first since 2012 that Emory men’s soccer has won the UAA championship. Derrick Beare expressed pride in his son and said he believes this year’s success is due to a similar cohesiveness he experienced during his own record-breaking season.

Joe Beare said his father’s individual statistics are “unattainable” for several reasons. His father played in more games during the season, received more minutes per game and the overall standard of college soccer has risen since his father played. He added that he “can say with certainty” no player is ever going to score 44 goals in two seasons again.

Courtesy of Emory Athletics

However, Derrick Beare said he believes his record should have been broken already since he did not play four full seasons at Emory.

“I only played two years,” Derrick Beare said. “That record, I find it unbelievable that it wasn’t broken.”

LeSure joked that her record has not been broken because Emory’s track and field program has not invited her back to share her knowledge. In LeSure’s eyes, a commitment to throwers’ development, including utilizing cameras to watch back throws and teaching athletes visualization strategies, is necessary for a future Emory athlete to beat her record.

LeSure is “not afraid” of her records being broken, and she offered advice to future Emory athletes about what it takes to accomplish similar feats.

“To break a record, you have to not even think about breaking a record,” LeSure said. “You just have to think about what excellence looks like for you.”

Hall of Famer Derrick Beare (82Ox, 84B) playing while attending the Atlanta campus. Beare went on to set the program record of goals scored in a single season. (Courtesy of Emory Athletics)