Emory University’s community involvement statement advertises its location in Atlanta as a valuable institutional feature: “For us, Atlanta isn’t just a location. It’s a relationship that has inspired partnerships and affiliations for years. And it’s a means to our mission of empowering community and making a real difference.”

Each year, the University hosts the Carter Town Hall and the Coke Toast — traditions that aim to welcome eager first years to campus through connections to major local cultural and economic powerhouses. The festivities also draw on Emory’s historical ties to former U.S. President Jimmy Carter, who is a university distinguished professor, and the University’s partnership with the Coca-Cola Company, whose founder Asa Griggs Candler provided the original land grant for Emory to relocate to Atlanta’s Druid Hills neighborhood in 1915. According to University President Gregory Fenves’s 2023 “One Emory” strategic framework, “Emory is a global research university, but [it] also [has] a responsibility to Atlanta, DeKalb County and the entire metro region.”

It is ironic, then, when the University conveniently neglects this community responsibility and remains appallingly silent on the issue of Cop City. The name refers to the Atlanta Public Safety Training Center, a police training facility already in the early stages of construction. If successfully implemented, the project would devastate the local environment and perpetuate police brutality on the area’s diverse population. The University’s stubborn silence is mirrored in the PATH Foundation’s proposal to construct a multi-use trail that would cause severe ecological damage to nearby forests along South Fork Peachtree Creek. Emory’s position on both causes stipulates how and when students should engage with the wider community, neglecting Atlanta’s past as a microcosm for the nation’s watershed moments and as a historical hub for advocacy and social change.

Student Activism Through the Ages

Atlanta is the cradle of the Civil Rights Movement and the home of visionaries like Martin Luther King Jr. However, the city is also situated in Georgia, a state that has historically fostered unimaginable violence against communities of color and where the wounds of slavery and Jim Crow laws are still visible. As an academic powerhouse of the region, student activism has long been described as an Emory tradition. In 1961, students petitioned former Emory President S. Walter Martin to admit Black students to the University. In 1969, 500 people rallied on the Quadrangle to present former University President Sanford Atwood with a list of eight protocols demanding action against racism. In 2020, after the brutal murder of George Floyd at the hands of Minneapolis police officers and the killing of Ahmaud Arbery by white residents in south Georgia, the Emory Social Justice Coalition sent a letter of demands to the University administration, asking for the creation of a more equitable learning environment. Most recently, the movement against Cop City has permeated campus, grasping the attention of many Emory community members.

Racist Ties

The $90 million militarized police training base will clear 85 acres of land in one of Atlanta’s largest green spaces, the Weelaunee Forest. Construction will include a mock city structure for practicing urban defense tactics and areas designated for testing explosives that reinforce the racist legacy of policing in America. Atlanta’s population is approximately 48% Black, yet between 2013 and 2023, 90% of people killed by the Atlanta Police Department (APD) were Black, according to the Mapping Police Violence database. History has taught us that Cop City will empower even more systemic violence.

The construction of Cop City is also inextricably linked to the environmental racism that it will perpetuate. The destruction of the Weelaunee Forest would have devastating effects on Atlanta’s climate, obliterating a forest known as one of the city’s “four lungs.” The Weelaunee Forest preserves air quality and prevents flooding from harming nearby predominantly Black communities. In these neighborhoods, asthma rates are among the highest in the nation, ranking in the 94th percentile, and surrounding waterways rank in the 96th percentile for toxic water pollution levels, according to the Climate and Economic Justice Screening Tool. Evidently, the destruction of this valuable green space is directly tied to harming the collective health of largely low-income, Black communities.

Cop City Sparks Student Protests

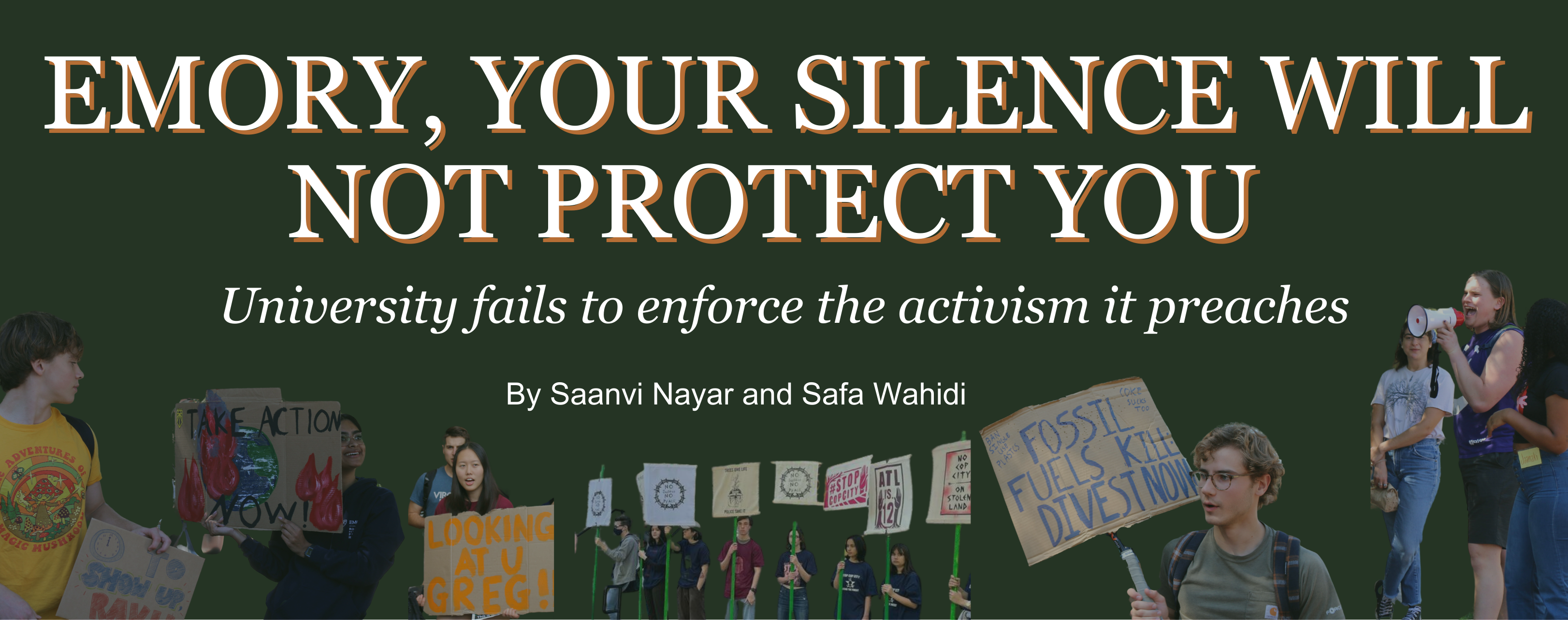

Learning from the city begins with understanding and fighting to dismantle Atlanta’s legacy of racist policing. Emory Stop Cop City is a student-led organization that aims to prevent the construction of the facility. The coalition has been organizing events, planning rallies and creating space for discourse since the fall 2022 semester.

On April 24, the organization hosted a gathering on the Emory Quad to facilitate community building through sharing art, music and food. The event evolved into a vigil for Manuel “Tortuguita” Terán, a forest defender who was shot by police 57 times when APD raided an encampment in the Weelaunee Forest. In response, students resolved to camp out on the Quad to demand the University condemn militarized police violence and the institution of Cop City. However, when protestors ignored threats of code of conduct violations, Emory Police Department (EPD) officers arrived on the Quad and threatened arrest if the students did not leave the area. Armed APD officers stood on the periphery of the Quad to “provide support to EPD, if needed,” Assistant Vice President of University Communications Laura Diamond wrote.

It is one matter to be apolitical or uninterested in activism-related organizing. However, it is a separate issue, one lacking moral responsibility, to fail to understand the severity of Emory calling armed police officers on their own students without warning. The University’s administration should be fundamentally built on representing and addressing the needs, goals and collective character of the student body. But when the EPD decided to send armed APD members to a non-violent protest, the University made a statement on its complicity in the construction of Cop City and its lack of moral responsibility toward its students. Emory made it clear that they deem it permissible to respond to peaceful civic engagement with threats of violence. As members of the Emory community, all students have a civic duty to hold the administration accountable. Every Emory student should envision their calls for change being met with tens of officers, wielding weapons, in the middle of our campus hub, in the dead of the night — and they should be just as angry as if this happened yesterday.

Soph Guerieri/Staff Photographer; Tiffany Namkung/Social Editor

The PATH Foundation

Similar to Cop City, the partnership between Emory and Atlanta’s PATH Foundation received a wave of opposition from a multitude of student groups and faculty signatories upon inception. Initially presented by Emory’s Office of Master Planning in November 2022, the proposal described a multi-use trail to potentially be built through parts of Emory’s property, including in Lullwater Preserve and Wesley Woods. Their stated goals included allowing for increased bike and pedestrian commuter access to campus. The recreational path would, however, also threaten fragile ecosystems inhabited by endangered species. A coalition of organizations released a joint statement on Feb. 25 opposing the potential path with signatures from students, staff, alumni, faculty and community members. Several months have now passed, and in a written statement to the Wheel, Diamond said that “PATH is conducting a feasibility study at the request of DeKalb County and no decisions about the project have been made.”

There are no decisions on the PATH Foundation and zero mentions of Cop City by Fenves. Emory has not just failed to take a stance; it has consistently refused to address valid student concerns.

Present Polarization at Emory

Tensions over Cop City rose again on Oct. 25 with an on-campus rally decrying the University’s financial ties. After a planned walkout, about 40 protestors entered Convocation Hall to present an updated list of 12 demands to Emory’s Director of Presidential Initiatives and Special Projects Anjulet Tucker. Protestors also condemned the ongoing conflict in Israel and Palestine, chanting the controversial phrase, “From the river to the sea, Palestine will be free,” and advocating for the University to “issue a statement in support of Palestine,” and “protect students from being doxxed.”

Fenves later sent an email to students, faculty, parents and alumni, denouncing “antisemitic phrases and slogans … repeatedly used by speakers and chanted by the crowd.” While Fenves was quick to call for students to seek “understanding over division,” he failed to explain what exactly constituted antisemitism or even mention Cop City — the original purpose of the protest.

No email Fenves will send will ever be perfect; the responsibility to represent an entire student body is nearly impossible when considering such contentious issues. But Emory University, where “the wise heart seeks knowledge,” has the ability to foster and encourage dialogue. When Fenves sent this email without advocating for productive civic discourse, he fostered an incendiary environment that further divided students and put others at physical risk.

Institutional statements are powerful in both benevolent and malevolent ways. Countless students currently feel hurt, angry and unsafe on campus. There is value in using empathy to engage with such nuanced political issues — reflecting on varied intentions, interpretations and identities. If Fenves had been more clear in his email about the protest, acknowledged why students gathered and encouraged a commitment for both sides to actively and empathetically learn from the other, there would be less polarization on campus.

Debate Over Respect for Open Expression Policy

Emory’s Respect for Open Expression Policy, which was implemented in 2013, affirms students’ rights to voice a wide variety of opinions. Although the policy protects freedom of expression, many organizations have also criticized the policy for permitting hate speech against marginalized students and providing exceptionally ambiguous guidelines on why a protest should be shut down. The Emory Social Justice Coalition called for expansion of the policy in 2020. The coalition stressed the power of the Chair of the Committee for Open Expression to terminate student protests and demanded that the University include more individuals in the process of determining when termination is necessary. The provision was not made. Debate over the policy was reignited on Oct. 21 when Professor of History and Director of Graduate Admissions Clifton Crais criticized Emory’s response to April’s Cop City protests. Crais wrote that the policy “is less a document that defends free speech and protest as a policy that attempts to police speech and protest.”

Crais is correct. The demonstrations against Cop City in April employed an Open Expression Observer, yet the students present were not notified of the plan to send EPD and armed APD officers in retaliation. In fact, student Oren Panovka (25C), who was present in the early hours of April 25, said that Stop Cop City organizers explicitly asked the Open Expression Observer to communicate their desire for APD and weaponry to not be implicated in the administration’s response. These requests were blatantly ignored, emphasizing the administration’s commitment to the performative upkeep of fostering advocacy on campus.

Jack Rutherford/Staff Photographer

Good, Necessary Trouble at Emory

“Emory is a place where we discuss and debate the issues that divide us — this is a foundational aspect of our mission to educate,” Diamond wrote in a University statement to the Wheel.

While the University has expressed its encouragement of student discourse, it is evident that Emory is inept at supporting the true passion for advocacy displayed by much of its community. What is even more alarming is that the University has repeatedly displayed tendencies to intentionally stifle student activism by condemning protests and disregarding critical debate. Emory’s website states that “Atlanta is progress — always driving forward in the face of social justice and civil rights.” This is correct, and promoting the University’s “synergistic” connection to Atlanta must include first recognizing Atlanta’s history as a city that has always flourished because of its young people — individuals who elected to engage in what former U.S. Rep. John Lewis (D-Ga.) deemed “good trouble, necessary trouble.”

The reality is that Emory is not just an Atlanta academic powerhouse. The University is also one of the largest employers in the metropolitan area and therefore has a profound influence over the region. The administration’s use of law enforcement to intercept peaceful protests fundamentally contradicts Emory’s mission to “create, preserve, teach, and apply knowledge in the service of humanity,” and its subsequent silence comes from a place of immense privilege.

“A democracy cannot thrive where power remains unchecked and justice is reserved for a select few,” Lewis said in regard to the George Floyd Justice in Policing Act. If Emory is truly “a community of impact where the greater good is balanced with individual interest,” the individual interests of the administration must not continuously overshadow its students’ views.

It is difficult to grapple with criticizing the University’s response and consequently being tasked to consider what an ideal response looks like. This is subjective to individual issues, but the acknowledgment and the prioritization of student safety should be the foremost priority. Whether it be sending armed cops to suppress a student protest or failing to address the ostracization and targeting of students involved in the Oct. 25 protest, Emory administration is consistently contradicting its baseline commitment to student activism.

Simply put, activism should not be institutionalized. Emory emphasizes advocacy as intrinsic to the institution, and therefore, the student body. Yet, our institution repeatedly stifles student perspectives and undermines civic discourse on campus, continuing to capitalize on the facade of encouraging student advocacy. Emory’s activism is reduced to a website tagline rather than tangible action; whether it be in the context of giving back to Atlanta or engaging with issues one cares about on campus, Emory, as a private institution, has and will primarily prioritize self-focused interests. Emory students, who support issues across different perspectives, can come together in the powerful realization that their activism is an individual identity, independent from Emory.

We often hear of the “Emory bubble,” a phenomenon in which Emory students seldom leave campus and integrate into the city beyond, resulting in an affluent but isolated institution entirely segregated from reality. Breaking this bubble is virtually unattainable without a campus cultural shift. Emory students need to continue to advocate for environmental protection, for marginalized communities and for a safer future. When the administration continually falls short, we are the ones continuously working to empower our community and redefine advocacy. We are only made better by divesting from the University’s commodification of our activism.

Correction (12/6/2023 at 2:51 p.m.): A previous version of this article incorrectly stated that Emory Police Department (EPD) and Atlanta Police Department (APD) officers “stormed” the Quadrangle. The article has been updated to clarify that APD stood on the perimeter of the Quad while EPD officers asked protestors to comply with requests to leave the Quad or face arrest.

Hayley Powers/Visual Editor