Gorō Miyazaki, son of beloved Studio Ghibli co-founder Hayao Miyazaki, will release his third feature film, “Earwig and the Witch,” on Feb. 3. The film will be the studio’s first fully 3D computer-generated project, representing the younger Miyazaki’s desire to rejuvenate Ghibli and propel it into modernity. At a press conference for the film, Miyazaki boasted, “I didn’t consult with the old guys [at Ghibli] at all.” Bold words, considering the “old guys” are responsible for creating some of the most adored animated films in history. The trailer for “Earwig” has garnered skepticism from fans and critics alike, with many questioning the need for a reinvention of the studio’s celebrated traditional animation style.

Can Miyazaki hope to possibly cement his place as one of Studio Ghibli’s renowned directors by way of technological reinvention? The relationship between father and son is known to be fraught, so it’s understandable that Gorō might aspire to one day fill his father’s shoes. Will “Earwig and the Witch” be the work that allows Gorō to live up to his name, or will its ambition alienate him from Ghibli fans forever?

Ahead of “Earwig and the Witch”’s release, the Wheel compiled a list of Ghibli films to watch on HBO Max.

The forest spirit Shishigami symbolizes the conflict between man and nature in ‘Princess Mononoke.’ (Studio Ghibli)

“Princess Mononoke” (1997)

“Princess Mononoke” (1997) is required viewing for anyone remotely interested in Studio Ghibli films. Released in 1997, the film is credited with introducing Studio Ghibli to Western audiences, and it bears all the hallmarks of a Hayao Miyazaki epic: a profoundly affecting (and impeccably crafted) narrative, countless gray shades of moral ambiguity and themes of nature and conflict in human existence. The film follows Ashitaka, the prince of a small village in feudal Japan, as he attempts to rid himself of a curse sustained while defending his people. Through Ashitaka’s journey, Miyazaki presents his own ruminations on human nature with a finesse that Studio Ghibli has never before seen.

The eponymous hill serves as the narrative and thematic centerpiece in ‘From Up on Poppy Hill.’ (Studio Ghibli)

“From Up on Poppy Hill” (2011)

“From Up on Poppy Hill” (2011) is the only film on this list directed by Gorō Miyazaki. In a rare collaboration between father and son, “From Up on Poppy Hill” is Gorō’s most successful work and is Ghibli at its most lighthearted. The Ghibli films of 2011 and 2013 highlight the studio’s shift to a more realistic storytelling approach. By shedding the fantastical elements of “Spirited Away” or “Howl’s Moving Castle” that scared us as children, the Miyazakis tell personal stories with a subtlety that the films of Ghibli yore eschew in favor of broader musings. This more grounded art direction allows both Miyazakis to present compelling individual narratives while encapsulating specific Japanese time periods with astounding facility.

That being said, “From Up on Poppy Hill” is not without its thought-provoking themes — the film revolves around two high schoolers’ plan to save their Yokohama clubhouse before the 1964 Tokyo Olympics, and the intersection of tradition and modernity features as one of the film’s key ideas. However, innovation can breed estrangement, especially when considering a formula as beloved as Studio Ghibli’s. Will the full CG of “Earwig and the Witch” be an innovation or an estrangement for the studio?

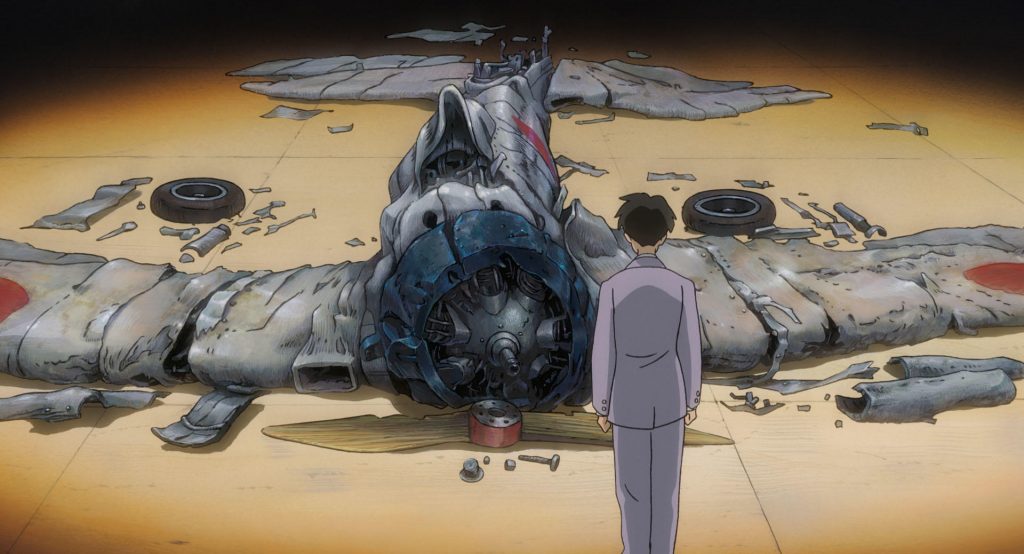

A still from ‘The Wind Rises.’ (Studio Ghibli)

“The Wind Rises” (2013)

“The Wind Rises” (2013) was believed to be Hayao Miyazaki’s final film, as, not for the first time, Miyazaki intended to permanently retire after its release. The film, which presents a fictionalized biography of aeronautical engineer Jiro Horikoshi, is regarded by fans and critics as Miyazaki’s swan song. This excellent feature is at once a meticulous portrait of prewar Japan, a contemplative meditation on the implications of Jiro’s planes being used in World War II and a heartbreaking, moving love story. The picture is, of course, a mesmerizing treat for the eyes, evident in the resplendent sunsets of its soaring dream sequences. However, the film is also a treat for the ears — the vast majority of its sound effects, including engine noises and an earthquake, are made by human voices.

It’s not a secret that “The Wind Rises” has semi-autobiographical elements, and you don’t have to look too hard to spot parallels between Jiro’s ambition for flight and Miyazaki’s lifelong pursuit of beauty. “The Wind Rises” is as close as we’ll get to a personal retrospective of Hayao Miyazaki’s life and work, and it’s a must-watch for anyone planning on seeing Gorō Miyazaki’s “Earwig and the Witch” in February.

A still from ‘The Tale of Princess Kaguya.’ (Studio Ghibli)

“The Tale of Princess Kaguya” (2013)

“The Tale of Princess Kaguya” (2013) is the only film on this list not directed by either Miyazaki. In Studio Ghibli co-founder Isao Takahata’s final directorial effort, the studio presents a masterful interpretation of a centuries-old Japanese fable. Takahata decided that the film should be animated in watercolor and charcoal style, a deviation from Ghibli’s usual iconic style, in order to better engage viewers’ imaginations. Ironically, the different art style is distracting and stunningly beautiful; the simple, folkloric beauty of the characters combine with placid tableaux of hills and straw houses to evoke a powerful sense of nostalgia, lending the work a serene beauty while paying homage to the story’s provenance.

With the same delicate touch as the artwork, the film presents a narrative with deep emotional resonance. Often, the animation pauses to capture the childlike glee on Kaguya’s face as she revels in the sights and sounds of Takahata’s exquisitely realized world, reminding us of the innocence of a youthful spirit. These wholesome moments contrast with our heroine’s aristocratic existence; Takahata juxtaposes Kaguya’s carefree nature with the prim society she inhabits to gently examine how the souls of women are dimmed in the name of nobility and the unfair way that pure souls are exploited by others. “The Tale of Princess Kaguya” shows there is a Ghibli beyond Miyazaki and that a change in art style can be successful. It’s an excellent film to watch in anticipation of “Earwig and the Witch.”

Cole Huntley (23C) is from London and is majoring in business and French studies. Some of his favorite things include bluegrass music, films about time travel and trying (not very successfully) to write poetry. Huntley is fascinated by the idea that people can either write an ocean of words as deep as a puddle or a puddle of words as deep as an ocean. Contact Huntley at chhuntl@emory.edu.