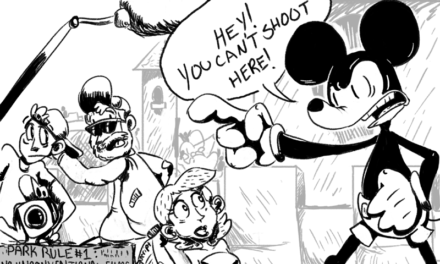

On Jan. 19, the College Board temporarily scrapped SAT subject tests and the SAT essay portion due to the ongoing pandemic. Over this past year, COVID-19 has forced American higher education to reconsider the role of standardized testing in college admissions. Accordingly, many universities, Emory among them, decided to go test-optional last year, temporarily allowing applicants to not send in SAT or ACT scores. While Emory went test-optional for just one year, given the inequities of standardized testing, admissions should permanently implement a test-optional policy to increase equitable access to higher education.

Emory and dozens of other schools recognized that during the pandemic, prospective applicants might face myriad obstacles that would hinder access to testing. But standardized tests didn’t become inequitable when COVID-19 struck; they have always disadvantaged those with less means.

It is no secret that students from wealthier families tend to score higher on the SAT. They can afford to study more, retake tests and hire tutors. Additionally, affluent students are more likely to get 504 designations, accommodations typically offered to students with anxiety or ADHD that provide the additional time or private space necessary to be on an even playing field with neurotypical students. Low-income students are less likely to receive these measures. Instead of assessing academic ability as they purport to do, the SAT and ACT, the other dominating college admissions exam, largely measure access to these opportunities and resources. Taken together, standardized testing is a poor way to measure scholastic aptitude, as scores are often products of socioeconomic conditions rather than intelligence.

Making the SAT and ACT optional is necessary to make college admissions more equitable. A study of more than 33 test-optional colleges found that minorities, women, Pell Grant recipients and disabled students were more likely to withhold their test scores if given the chance. Emory going test-optional helps these students out by giving them the freedom to choose, and it helps Emory: one study found that schools that go test-optional can yield a higher overall number of applications and a higher proportion of enrolled low-income students.

However, making standardized tests optional will not solve all of the college admissions system’s inherent problems. Being born wealthy enables future success in many more ways than overperformance on tests. America’s socioeconomically disadvantaged are set up to fail, and this inequity has no easy solution. Emory going test-optional won’t cure this disease, but at the very least, it mitigates the flaws of an inequitable system.

As such, Emory must actively limit their influence in admissions. According to Dean of Admissions John Latting, Early Decision I applicants last fall who submitted test scores held a slight advantage over those who did not. This should not be the case. If simply going test-optional does not yield meaningful increases in accessibility or equity, as Emory’s results and research suggest, Emory should prevent admissions staff from impairing those who choose not to send their scores. Otherwise, the decision will prove performative.

Just as the wealthy adjusted to standardized testing by paying for preparation and retaking tests, they will find other ways to gain advantages through grades, extracurriculars and internships by virtue of nothing but their parents’ affluence. The legacy system, which preferences applicants whose parents attended the university in question, and the absurdly high cost of a college education are probably not going anywhere soon. Going test-optional indefinitely, clearly, will be no panacea. But it would be a major step toward remaking Emory in the equitable, accessible image to which it aspires.

If Emory admissions officers truly wish to build a diverse, groundbreaking class of students, they should evaluate how the standardized testing requirement reinforces class and race inequities. If not, they’ll continue to miss out on exceptional students and remain forever ranked 21.

The above editorial represents the majority opinion of the Wheel’s Editorial Board. The Editorial Board is composed of Sahar Al-Gazzali, Brammhi Balarajan, Viviana Barreto, Rachel Broun, Jake Busch, Sara Khan, Sophia Ling, Martin Shane Li, Demetrios Mammas, Meredith McKelvey, Sara Perez, Ben Thomas, Leah Woldai, Lynnea Zhang and Yun Zhu.

The Editorial Board is the official voice of the Emory Wheel and is editorially separate from the Wheel's board of editors.