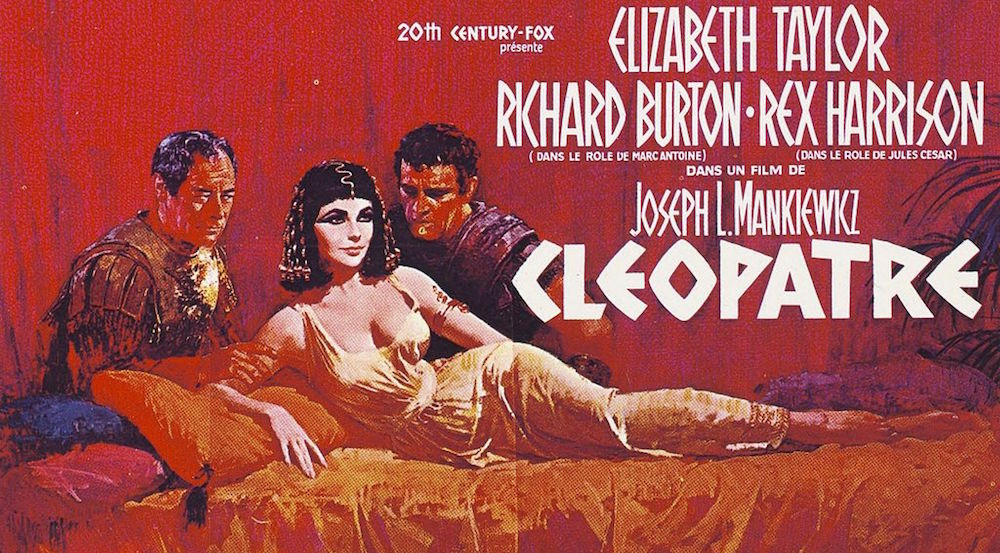

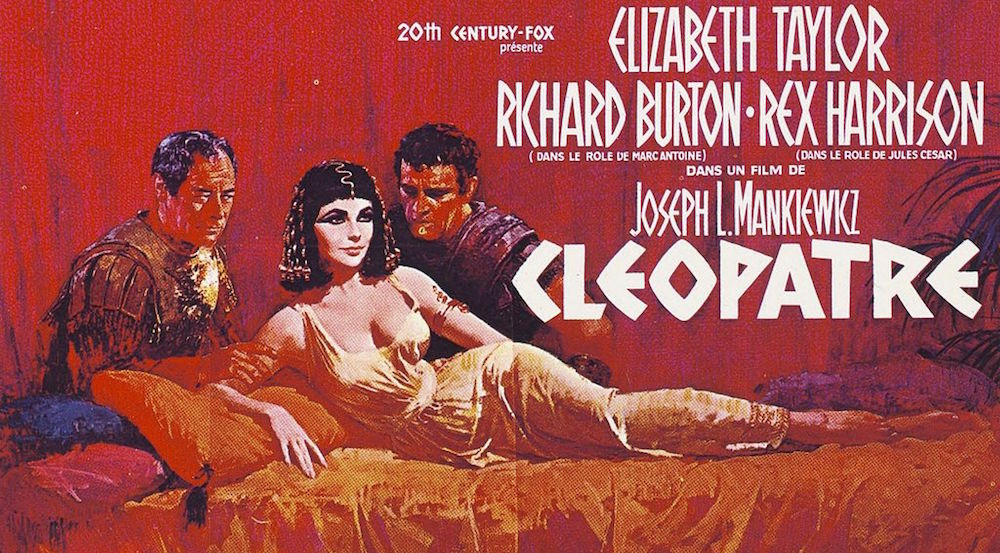

Cultural appropriation and “whitewashing” in popular media are issues that have plagued minority communities within the U.S. for centuries. Whitewashing is a metaphor used to explain how the achievements and cultural milestones made by people of color have historically been erased and appropriated by the white population. Since as early as the 1930s, Hollywood has made white actors portray people of color in films, such as “Charlie Chan Carries On” (1931), in which a middle-aged Asian man is portrayed by Warner Oland, a white actor, and “Cleopatra” (1963), in which Elizabeth Taylor, a white actress, played the Egyptian queen Cleopatra.

According to a study conducted by The University of California — Los Angeles, whites eclipse minority groups in every aspect of film and media, ranging from acting to directing films.

The being said, racist tendencies have not been limited just to Hollywood. In the music industry, artists such as Gwen Stefani, Avril Lavigne and Elvis Presley have each played a role in cultural appropriation in a bid to gain attention. As early as the 1950s, Presley, also known as “The King of Rock and Roll,” exhibited cultural appropriation when the idea of rock and roll was conceived.

According to Larry Ford’s “Geographic Factors in the Origin, Evolution, and Diffusion of Rock and Roll Music,” rock and roll originated from African American blues musicians, such as Robert Johnson, and a mixture of other primarily white genres such as country and pop.

In the early 2000s, Stefani began a publicity stunt centered on her interest in Japanese culture that quickly spiraled out of control. In 2004, Stefani hired four backup dancers who she named “Love,” “Angel,” “Music” and “Baby,” respectively, after the title of her album. These four girls were forced to speak in Japanese at all public events and were known as the “Harajuku girls.”

Asian American comedienne Margaret Cho publicly criticized Stefani by comparing the Harajuku girls to blackface: “Even though to me, a Japanese schoolgirl uniform is kind of like blackface, I am just in acceptance over it, because something is better than nothing. An ugly picture is better than a blank space, and it means that one day, we will have another display at the Museum of Asian Invisibility, that groups of children will crowd around in disbelief, because once upon a time, we weren’t there.”

However, the works of Stefani and Presley were not nearly as controversial as the rise of a relatively new artist Amethyst Amelia Kelly, better known by her stage name “Iggy Azalea,” whose fame and image are solely dependent on her skills of mimicking people of color.

Azalea is an Australian rapper from Mullumbimby, New South Wales. At the age of 16 she flew to Miami, Florida to pursue a career in rap. Azalea had her first major breakthrough in the U.S. in early 2014 with her U.S. debut single “Fancy” featuring pop vocalist Charli XCX. The single, released by Island Records, became a number one hit on the US Billboard Hot 100 chart.

Many of her fans might find her success story inspirational, but Azalea has proven to be an incredibly polarizing figure. Many find her “rap skills” to be insulting due to her use of a southern accent in her songs that does not reflect her native Australian accent. Others find her ability to rap at all debatable.

Azealia Banks, another female rapper, who grew up in Harlem and achieved widespread acclaim for her album Broke With Expensive Taste recently, was interviewed by Hot 97 Radio co-hosts Ebro Darden and Peter Rosenberg about her stance on hip-hop culture and Azalea’s recent fame and Grammy nominations.

During the interview, Banks focused on her frustration of cultural smudging that occurs in modern-day music, especially in the hip-hop genre. She explains that America is a country that was built on the backs of slaves and that modern capitalism is essentially the result of slave labor: “Everybody knows that the basis of modern capitalism is slave labor and the huge corporations that are still caking off of slave labor.”

She continues by arguing that this undercurrent of racial prejudice in America has continued on in pop music in the form of cultural appropriation as white rappers are becoming more prevalent and famous than black rappers: “That Macklemore album wasn’t better than the Drake record. That Iggy Azalea [record] is not better than any black girl that’s rapping today. And when they give those awards out — ’cause the Grammys are supposed to be accolades for artistic excellence — Iggy Azalea is not excellent […] When they give these Grammys out, all it says to the white kids is ‘you can do anything you put your mind to’ and it says to the black kids ‘you don’t have anything, you don’t own anything, not even the things you created for yourself.’”

At the end of the day, whether or not everyone agrees with Banks’ sentiment, her argument brings up a question that people have been asking for decades: Where do we draw the line? Is it okay to transcend these cultural barriers? Fifty years ago these questions may not have even been brought up. But as America continues to evolve and recognize the nuances of culture, the underlying problems of racism have gradually become more important.

The fact is that even though some might view the mimicking of other cultures by popular artists as harmless, the underlying message reflects something far more sinister. Stefani and Azalea are conveying a message that it is acceptable to steal the works of people of color in the name of art and entertainment, similar to how blackface was socially acceptable in the early 1900s. Americans must remember that race does matter and that it is necessary to be respectful of other peoples’ culture.

Jesse Wang is a College freshman from Audubon, Pennsylvania.

The Emory Wheel was founded in 1919 and is currently the only independent, student-run newspaper of Emory University. The Wheel publishes weekly on Wednesdays during the academic year, except during University holidays and scheduled publication intermissions.

The Wheel is financially and editorially independent from the University. All of its content is generated by the Wheel’s more than 100 student staff members and contributing writers, and its printing costs are covered by profits from self-generated advertising sales.

I’m so glad this freshman was able to take a course in “African-American Studies” last semester. Thanks so much for educating all of the ignorant whites!

As they should be educated! As we ALL should.

Yep, that’s why I love how Indians and Asians treat racism. They don’t care. The less you care, the less people will be racist towards you.

1. There is no evidence if Cleopatra was black or white.

2. Opinions are opinions are opinions. Everyone is entitled to have one. You have yours he has his.

3. Of course cultures influence one another. What he is highlighting is the issue of CULTURAL APPROPRIATION. Of course cultures borrow from cultures. However, some of the artists Jesse is referring to is using cultural elements from minority cultures that aren’t there’s out of context ! It’s the danger of taking certain cultures and making them as icons that can later lead to stigmas and stereotypes.

I am a Multi-Racial Japanese American, and this issue is REAL out here. So kudos to you Jesse!!

His argument isn’t that cultures shouldn’t borrow from one another.

His argument is to warn of the dangers of culture appropriation. I think

you mis-interpreted the article…

And your arguments and examples are logically beside the point and out of context.

deny blacks access to medicine?? Are you freaking kidding me? Asians not wear jeans?? have you lost it?

Completely out of context….

It’s cool cultures borrow from one another, but it’s a different story to take culture and stigmatize it for your own benefit. Because of the social media and icons that do this today, much of the minority class face micro aggression and have to battle stigmas every single day!

& Actually I would argue that Jazz came from the blues and the blues came from African AMericans.!!!!!!

Of course cultures share ideas. However, the issue is misrepresentation of culture. This causes

false stereotypes and stigmas. It’s taking cultural elements from a group and using them to promote a stereotype the wrong way.