I’d like to make a case against homework, or at least, the huge amount of it that college students have. Let me start by saying that I am not a slacker. I’ve always been meticulous about my schoolwork, and it’s served its purpose, I suppose, in getting me the grades I wanted. As time goes on, however, I’m less inclined to believe that it has served its normative purpose, which is to cultivate both genuine learning and the establishment of a framework for lifelong learning. Instead, the system of schooling that we’re currently functioning under serves to create a barrage of jaded young adults, desperate to never crack a textbook again.

The most directly relevant angle to look at this issue from is just simple math: less reading (and other work) can result in more effective reading and more reading can create less effective reading. For example, I’m writing this as a reactionary backlash to the slew of lengthy, technical readings I’m supposed to be doing for upcoming classes. I got lost in the dense, endless pages of the articles and essays and started thinking about the weather, Thanksgiving, the new “Hobbit” movie, anything but what the reading was about. And then I ended up here, writing this.

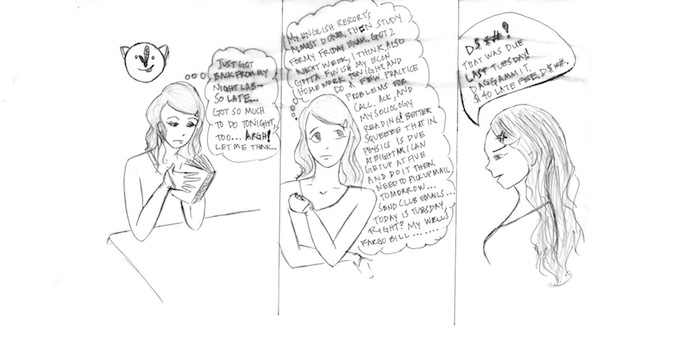

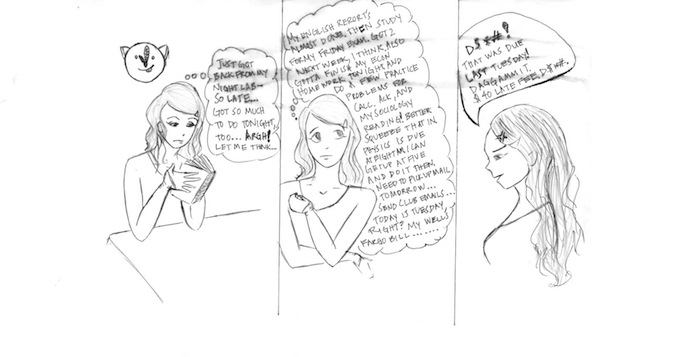

Professors have a tendency towards fear of incompletion. They think that if they don’t cram absolutely everything there is to know about the subject into a course, they’re failing. What happens in their drive to consummate their ideal curriculum, though, is leaving behind their students in the dust. In practice, this means that students read poorly, if they read at all. I euphemistically call it “power reading;” the reality is just me skipping sporadically around the page in hopes of running into keywords. It doesn’t matter how good someone is at time management, no one can read all the things he/she is supposed to for class and still manage to maintain sanity, a decent sleep schedule and an extracurricular life, all of which should be just as important to a student’s life as academics.

Which leads me to my next point: there is life outside of school. If college is really what it proposes it is, it should be a time for exploration of oneself and of the world. We’re supposed to be trying new things and expanding our experiences, but what we’re doing instead is spending our days and nights holed up inside staring at books and laptops.

This point really hit me hard this month. I had the opportunity to travel with my dad for a week in Peru, visiting farming co-ops in the foothills of the Andes and learning how loans from a social impact group, Root Capital, had improved both their businesses and their standards of living. As such, I took all of last week off, and the returns have been great – it was absolutely the most valid learning experience of my semester so far. Other examples abound, simpler ones, such as exploring the endless ethnic markets of Buford Highway, spending a day constructing a fence at a community garden, even writing this article for the Wheel. They’re all times when I privileged mind-expanding experiences over doing homework. The old Mark Twain quote comes to mind, “I never let schooling interfere with my education.” Academia is but one strain of knowledge, not the only one.

Lastly, and perhaps most significantly, our prevailing system of learning in which too much to do is packed into too little time is creating sickness – biological, social and psychological. Look around you. Sleep, diet and exercise are compromised for the sake of fitting one more homework assignment or one more hour of studying in. Colds spread like wildfire. We’re almost universally stressed; many have anxiety, some are depressed. Binge drinking as a means of coping and letting go is easily observable, as well are means of avoidance like sleeping all day. We cling to our phones for dear life because our social media gives us momentary distraction. All in all, school has turned from a liberation of the mind into a war of attrition. Students are so overwhelmed that on the whole, they’re not learning anything, or if they are, it’s for the sake of a degree, not for the intrinsic value of education.

It all boils down to this: we’re not teaching people how to learn by piling on more readings, assignments or exams. We’re teaching them how to cut corners, cheat the system and get by. I can only speak for myself, but I certainly don’t just want to get by. I want to be enthralled with both the opportunity and the substance of my schooling. My friend recently wrote to me in a letter about an anecdote from her Animal Behavior class. Her professor, a former veterinarian, had listed “Appreciate the Pig” on a list of objectives for the course. She had explained to the class that this had been an objective on a syllabus for a Swine Management class she had taken in vet school. It meant that you should always step back from the intricacies of what you’re doing in class and just appreciate the vastness of what it is you’re getting to learn and getting to do. You should be absolutely astounded by how unlikely and chimerical whatever you’re studying is and equally as floored by the opportunity to study it.

My friend wrote to me, “While you’re managing your swine, remember to appreciate the pig.” This is my ideal education and the key to lifelong learning. The way to get to it is not as philosophical and flimsy as it might seem to be.

First, professors should assign less work. They should think long and hard about what it is they want their students to get out of the class, and they should construct a syllabus around those essential goals. Second, students should buy into the process of learning. I’ve been entirely disenchanted since coming to Emory. I went to a small high school where learning for the sake of itself was emphasized, leading to an eager student body. In college, the trend is towards doing as little work as possible for the end-result of a degree. Like I said before, it’s understandable. But with higher quality, lesser quantity work, students should make a commitment to their studies.

If these two things happen to create a symbiotic relationship between student and teacher, a more harmonious learning community will rise. Students will be healthier, happier, more inclined to try new things and expand their repertoire; professors will be just as happy because more of their students will be taking a genuine interest in their attempts at teaching. Let’s right this wrong.

Joanna Satterwhite is a College sophomore from Atlanta, Georgia.

The Emory Wheel was founded in 1919 and is currently the only independent, student-run newspaper of Emory University. The Wheel publishes weekly on Wednesdays during the academic year, except during University holidays and scheduled publication intermissions.

The Wheel is financially and editorially independent from the University. All of its content is generated by the Wheel’s more than 100 student staff members and contributing writers, and its printing costs are covered by profits from self-generated advertising sales.