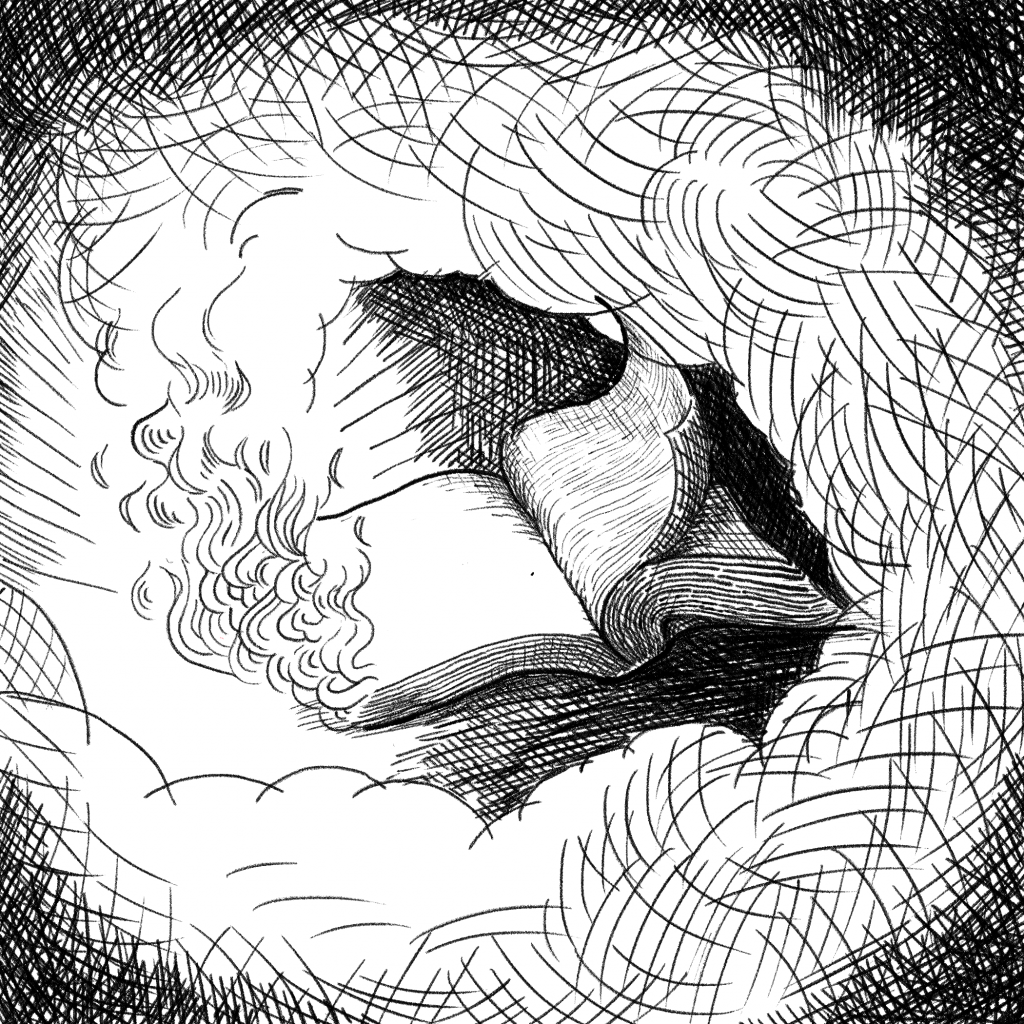

Anusha Kurapati/Emory Wheel

My favorite story book when I was little was “And Tango Makes Three,” written about two male penguins raising a baby at the zoo. But it wasn’t until the fourth grade that I learned my beloved book had another name: banned. Apparently, the story of the same-sex penguin couple was an inappropriate topic for some schools and libraries, who removed it from the shelves. I learned this during an elementary school presentation on banned books, thinking: How can you ban a book? What happens if I read a banned book? Will I be in trouble? Our teachers excitedly explained how ideals of free speech and press allow us access to books like “And Tango Makes Three” and “Captain Underpants.” We learned that we should celebrate the fact our freedom to read was protected. However, not all schools promote this sense of intellectual freedom.

Book banning and censorship have held a long-standing presence across time and cultures. From book burning to banning, efforts to contain and control ideas persist. The first book to meet substantial resistance in the United States was “Uncle Tom’s Cabin” ; the pro-abolition agenda of the novel drew enough attention from the Confederacy to warrant a status of “banned.” Following this first move, challenges to books by schools and libraries spread across the U.S. like wildfire, and those efforts are still ablaze today. But the effort to ban books sparked a movement of free press celebration that strongly rivals censorship; banned books are read and celebrated because their significance in historical and cultural conversations is only amplified, not diminished.

When we look at the list of banned books, one thing is clear: The effort to ban certain books is an attempt to clear the global narrative of prejudice, violence and sexuality. These key issues serve as the common factor on the banned books list. Excluding titles that contain important historic or modern themes suggests that history is malleable. It grants the power to pick and choose the story we want to tell and reiterates an incomplete story. Book banning alienates important topics and removes the possibility of conversation on these essential yet complicated issues. If anything, this alienation only amplifies the necessity of holding conversations surrounding these issues.

The most common reason books are banned is for the inclusion of violence, explicit language and sexuality. But books are a reflection of the time they are written in; the inclusion of these themes imply the importance of them in cultural and societal development. For instance, “To Kill a Mockingbird” is commonly banned for offensive language and racism even though the book is written to directly criticize racist attitudes and themes. Similarly, encompassing the horrors of the Holocaust, “Maus” earned status on the banned book list for nudity, suicide and violence. Without these topics however, understanding the gravity of the horrific dehumanization of Jewish people during the Holocaust would not be possible. Banning these books causes an incomplete understanding of essential themes that constitute our modern day. And, conversely, having the ability to access them through free press is a reason for celebration.

Rivaling fierce resistance, the banned book list keeps growing even today. As new intricacies to core issues like racism and sexuality arise in modern literature, so do challenges to them. For addressing the topic of police brutality, “The Hate U Give” was banned on the basis of profanity and promotion of anti-police messages. Similarly, voicing an omen of restrictive women’s rights, “The Handmaid’s Tale” made the list because of sexuality, profanity, suicide, violence and anti-Christian themes. The list goes on and on. As more and more titles addressing controversial issues are published, the more titles are added to the banned books list.

The irony of the effort to censor books is that commonly banned books are some of the most famous. Banning books simply shines a spotlight on them. While some fight to conceal uncomfortable and raw topics, others recognize how crucial exposure to these topics are, just as my elementary school did years ago. A holistic understanding of historic and modern culture is incomplete without the recognition of violence, sexuality and racial prejudice. It is impossible to have a conversation about modern society or culture that excludes these themes, so why attempt to conceal them?

The duality of banned books simultaneously represses and encourages discourse on so-called inappropriate topics like sexuality. What was intended as a device of censorship is instead fueling literary fervor. Schools like my own celebrate our freedom to read the pages marked “dangerous” by those too uncomfortable with depictions of racism, violence and sexuality. Perhaps this is a silver lining of censorship: Banning books draws more attention to them. More importantly, those books need that attention. Banning books does not negate the cruciality of their topics in modern discourse. We need to keep reading and keep conversing, because the topics that get books banned are the topics most crucial in our society.

Lena Bodenhamer (24C) is from Fort Collins, Colorado.

Lena Bodenhamer (24C) is from Fort Collins, Colorado, majoring in philosophy, politics and law. Bodenhamer is an aspiring human rights lawyer who also enjoys running and exploring Atlanta.