On a Sunday evening in the beginning of December, I took my seat in the audience of a somewhat modest theater surrounded by people, all of us converging to see one thing: puppets.

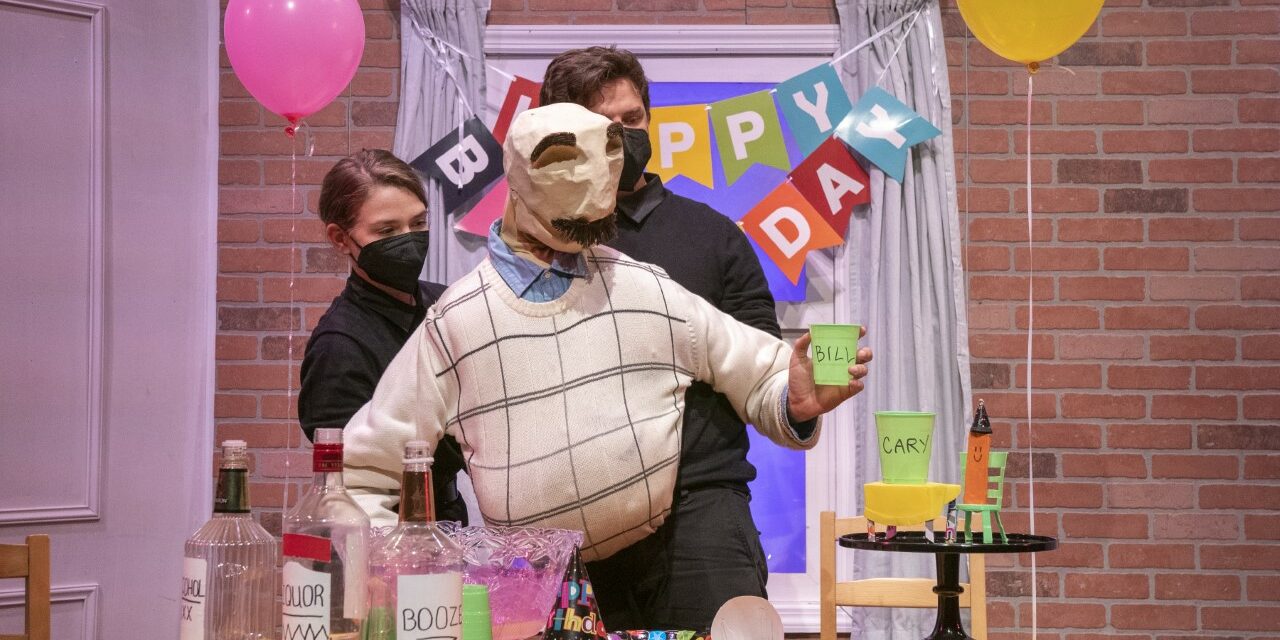

While I sat with all those other people in the theater, waiting for the show to begin, I surveyed the stage. The show was entitled “Bill’s 44th” and the set was a typical apartment, complete with reclining chair, television and dining room table and chairs. At that point, there was no indication that I was about to view a puppet show. All signs pointed to a human subject.

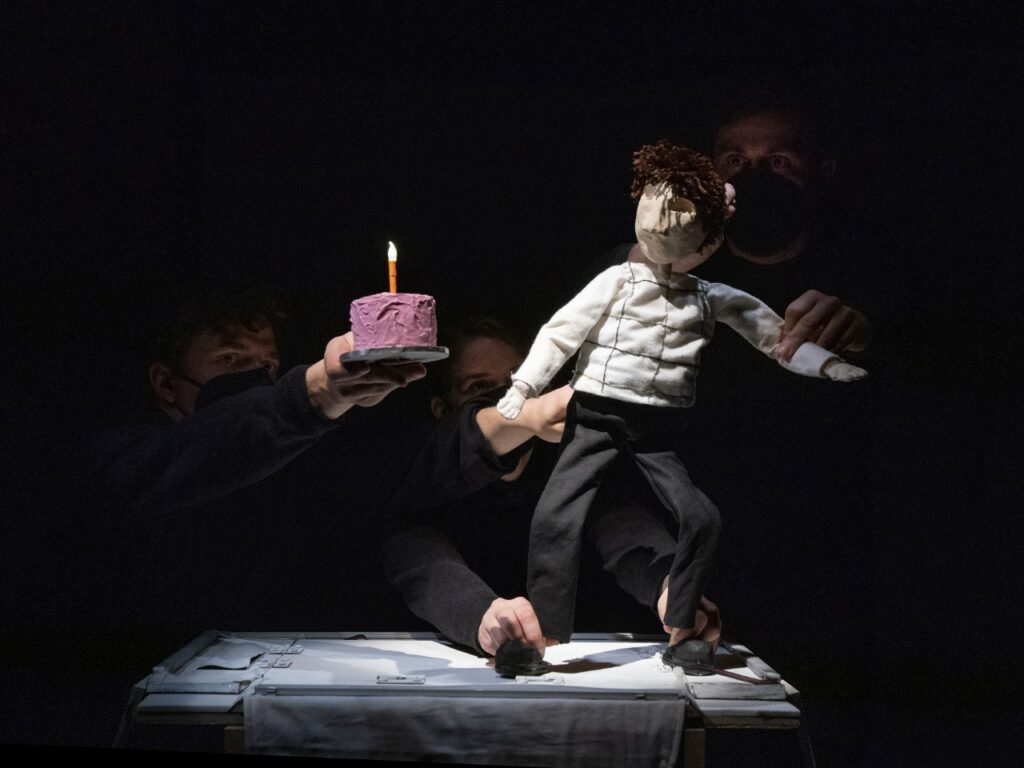

When the music began and the lights came up, three bodies entered onto the stage: two nameless puppeteers dressed in black and Bill, a head, a torso and two arms. I tried to mentally untangle the hands controlling Bill, to understand which puppeteer was directing which part of Bill’s body. Eventually, though, their bodies melded together. Bill became all three bodies united into one entity. He glided with a silent, awe-inspiring energy across the stage.

Courtesy of Richard Termine.

The frog green building of The Center for Puppetry Arts stands at the corner of Northwest 18th and Spring street in Midtown Atlanta. An appropriately colorful facade that houses over 5,000 puppets and puppetry artifacts and produces over 600 shows a year, Atlanta’s Center for Puppetry Arts opened September 1978, with Jim Henson and Kermit the Frog joining founder Vince Anthony for the ribbon cutting ceremony.

In the 45 years since, the Center for Puppetry Arts has become one of the preeminent institutions dedicated to the education and creation of puppets. Their facility includes the Worlds of Puppetry Museum, a collection that incorporates puppetry work from across the globe, including an exhibit dedicated to the work of Henson.

These exhibits give context to an art form that has existed for millenia. While walking through the exhibits, I became enraptured with the puppets. They are objects that vary in form, from marionettes on strings, to massive faces which loom above you, to a simple shadow created by light and negative space. The rich history of the puppet, and its continued ability to enthrall, demonstrates the power of an object in space and movement to conjure any and all kinds of subjects and emotions.

“Puppetry is fundamentally about a story, but it includes design and dance, choreography,” Center for Puppetry Arts Producer Therese Aun said. “It is the nexus of all art … It is all the visual arts.”

Courtesy of the Center for Puppetry Arts.

This convergence of art forms is what separates puppetry from other forms of theatrical arts. While traditional theater may incorporate multiple forms like dance and song, Aun said that it is ultimately limited by what a human can be.

“Puppets are the distillation of whatever they are meant to communicate,” Aun said.

As an example, Aun cited a show she led in which a doctor, portrayed as a headless puppet, attends to his ailing wife. Although his hands treated her, Aun said that his lack of a head demonstrated that he “had no eyes or ears to hear” her suffering. Because puppetry can be this literal, Aun said that audiences “don’t have to make a leap of faith” to see characters as they are.

The puppet’s ability to be exactly what it is allows it to transcend human communication. This makes puppetry a naturally accessible medium as it is representational and a hybridization of so many different visual and aural forms. As such, the Center for Puppetry Arts places an emphasis on encouraging all people, regardless of ability or circumstance, to learn about and enjoy puppetry. The Center offers sensory-friendly days that are particularly catered to patrons with sensory sensitivities. On these days, Center staff adjust lighting and sound to be more even and less harsh, so that the museum and shows are more approachable.

The accessibility lies in the unique way puppetry situates itself in reality and in the imagination of its audience.

“The puppet lives in this in-between world,” Aun said. “It has all the intention of human interaction and emotion, but it lives in a different form so it dials back fear of that other human and lets you as an audience person feel comfortable.”

The combination of these transcendent qualities—the existence of puppetry in an interstitial world and its ability to be the object it seeks to represent—lends an inherent accessibility to the art form. It is easy for any viewer to fall into the worlds created in a puppet show because they are so inviting.

As a representational form, puppetry brings the audience into a world that has a basis in reality and pulls inspiration from real issues and emotions without the same limitations as our world. Because it exists in its own world, there is room to explore subjects in unconventional ways.

Aun described a puppeteer she used to work with who would put a blank piece of paper on the ground and ask where the energy in that paper was. Aun and the other people studying with this puppeteer all found the hot-spot of energy on the paper. There is energy, even in an empty space.

“A puppet is nothing but an object unless there’s a human behind it, giving it life and intention,” Aun said. “When you pick up an object, the puppet, it has its own energy, and then when you add the energy of the audience to it, it’s this real circle of energy that is hard to describe.”

Puppetry is about taking all the energy that exists in an empty space, in the puppet itself and in the room where puppet and audience converge, and making it say something. All this energy feeds the emotion and intention of the puppeteer and the puppet, and by effect, the audience.

That same puppeteer would also observe his surroundings in day-to-day life. According to Aun, one day he noticed a rusty piece of metal while walking to his studio. From that simple piece of tin, he was able to build a puppet show whose subject blossomed around this initial observation.

“The puppeteer’s inspiration is not limited to this world,” Aun said. “They are inspired by a lot of things that are ordinary to a lot of people.”

With puppets, something as ordinary as celebrating a birthday becomes a setting rife with meaning, as it does in “Bill’s 44th.”

Courtesy of Richard Termine.

In our conversation, Aun mentioned that puppets do things that humans cannot. That is part of what sets the bar of puppetry—it needs to require puppets to tell the story. I thought of those words while watching “Bill’s 44th” because the puppet is human-like and felt relatable as a human, but Bill’s existence as a puppet situated him in that in-between world that Aun described. In this world, balloons can become friends and enemies, and a videotape can explode the TV into a smaller puppet show of a person’s life.

“Puppetry has its own language. Really good puppetry has very little language because the puppet is expressing everything that the narrative has to communicate,” Aun said. “‘Bill’s 44th’ has no language, it’s all about movement because the movement of that language, how it looks and how it moves in the world, will communicate everything that the artist wants it to communicate.”

The boundaries between reality and imagination are fluid in a way that allows the puppet and puppeteer to explore emotions and experiences that don’t need words. The puppets in “Bill’s 44th” brush past the weeds and noise of day-to-day life and go straight into a deeper, intrinsic part of the brain.

“Puppetry is the notion of distilling things down to their essence,” Aun said. “When a puppeteer decides what a puppet is going to be and what it’s going to do and therefore what it’s going to represent, it’s all about carving away everything but the essential communication pieces. In a world where we’re just bombarded with stuff all the time, it’s like poetry. To me, puppetry is like poetry, it is communication brought down to its most essential expressive place.”

Watching “Bill’s 44th” felt like reading poetry. In the absence of language, the motions and actions of the show came across with stunning clarity. The experience of watching puppetry can be described in many ways, but perhaps most importantly it circumvents the rational mind and embeds itself into the soul. The beauty of this art form is that no matter how complex and intricate the machinery of the puppet may be, it is fundamentally about the most basic parts of humanity: movement, action and emotion.

Bridget Mackie (she/her) (25C) is from Cary, North Carolina and majoring in English. Outside of the Wheel, Bridget likes to make art, knit sweaters and collect plants.