(Emory Wheel/Jay Jones)

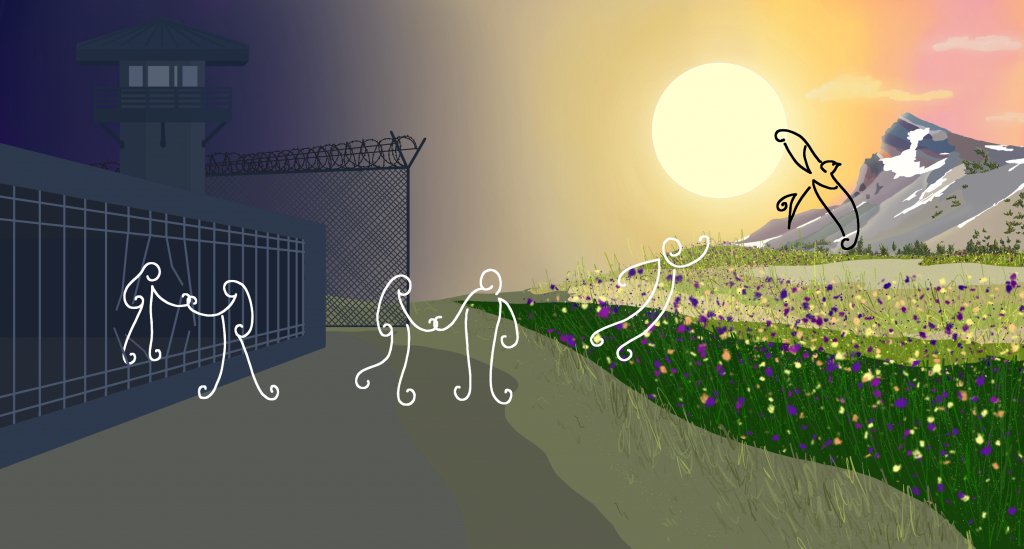

The transformative possibilities of defunding the police and abolishing prisons have entered the popular imagination over the past year. Much of the momentum on the streets gained over the summer of 2020 has slowed down, but millions of people were exposed to the radical framework of abolition. Now that it’s LGBTQIA+ Pride Month, queerness will enter the spotlight as corporations create rainbow versions of their logos, rainbow products are placed on shelves and queerness is depoliticized in the name of inclusion. However, as abolition and transformative justice rise in popularity, queer folks and abolitionists have a responsibility to draw connections between queer and trans liberation and the elimination of carceral systems. Prison abolition is a queer issue.

Queer people have long been criminalized and faced significant harm at the hands of the prison industrial complex. Anti-sodomy laws are some of the more obvious examples, originating in 16th century western Europe and spreading to many of its colonies as a means of social control and legislating morality. In the mid-20th century, when gay cruising was criminalized and highly policed, surveillance and entrapment were key tactics for the state to control queer people’s relationships with the fear of being exposed, disowned, fired, attacked or arrested. Similarly, many queer spaces, including bars, theaters, bookstores and magazines, were and are policed by obscenity and indecency laws. Laws against so-called cross-dressing and impersonation—in other words, wearing clothes of the supposedly wrong gender—have a long history as well. One of the most infamous was New York’s three-article rule, in which people were required to wear three pieces of so-called correctly gendered clothing. This informal rule allowed police to harass queer folks defying gender norms, most often drag queens, trans people and butch lesbians.

Queerness has also long been pathologized, as many LGBTQIA+ people have been forcibly committed to mental institutions and hospitals under the guise of curing deviant sexuality. Queer people, especially queer sex workers of color, were also heavily policed during the AIDS crisis through quarantine orders (though ineffective) and a ban on entry for immigrants with HIV. Policing and violence against queer people, especially queer people of color and Indigenous people who reject settler sexuality, has transformed significantly over the last several centuries, but there is no doubt that our community has been continually harmed by surveillance, policing, and the entire prison industrial complex.

The harms of prisons and policing against the queer community are still very much alive, making the depoliticization of queer pride even more dangerous. One of the most highly politicized attacks on our community over the last few years was North Carolina’s proposed bathroom bill in 2016, in which trans people would have been required to use the bathroom of their assigned gender, rather than the most affirming one. Transphobic legislation has had a resurgence over the past year as well, including not only similar bathroom bills but also restrictions on trans health care and trans participation in sports. Many of these bills directly rely on the threat of carceral punishment (e.g. jail time for parents who provide youth with trans-related healthcare), but even those without explicit criminal implications rely on the state’s power to dictate morality and to police those who do not conform.

In addition to legal discrimination, many queer people also face harsh rejection from their immediate family and risk losing access to housing and financial support. Unhoused people are highly policed regardless of their sexuality, but 40% of unhoused youth are queer; unhoused queer youth are 200% more likely to be arrested for status offenses such as truancy and running away than their straight cisgender counterparts. Additionally, unhoused queer folks are often pushed into criminalized economies like drug sales and sex work. This is especially dangerous for trans women of color, who are subjected to assault, police harassment, profiling (such as with the Walking While Trans law), and arrest. Following the footsteps of the quarantine orders in the AIDS crisis, HIV transmission has been criminalized in most U.S. states, disproportionately affecting queer people, especially queer men of color. This also extends to immigrants, especially those in ICE detention facilities, who frequently face violence, denial of healthcare, and solitary confinement based on a positive HIV status.

Queer people, especially those of color, are overrepresented in both the juvenile and adult prison systems and are more likely to face abuse and violence from police and prison officials. It is clear that our community confronts a colossal amount of violence every day, particularly at the hands of police, prisons and the prison industrial complex. How can we possibly liberate ourselves and each other if we do not center fundamental social transformation, including prison abolition, in our movement?

Not only is policing in our community’s history, but resistance is too. The most famous example is the 1969 Stonewall Riots, an explicitly anti-police riot following a raid of a queer-friendly bar. Riots, uprisings and rebellions like the Stonewall Riots occurred across the country in response to police brutality and surveillance, including the Compton Cafeteria Riots in San Francisco, riots at the the Black Cat Tavern in Los Angeles, Dewey’s Lunch Counter Sit-Ins in Philadelphia, and riots following a police raid of Ansley’s Mini-Cinema in Atlanta. ACT UP also vocally denounced police brutality and persistent arrests at its actions during the AIDS crisis, and the gay liberation movement collaborated with the Black Panther Party to resist state violence.

Additionally, all queer resistance in the U.S. today is built on the continual resistance of Indigenous peoples to settler sexuality, heteronormativity, mononormativity, the nuclear family, the gender binary and the violent state supression of Indigenous knowledge of kinship and family. Resisting settler sexuality means resisting settler policing. In solidarity with their Indigenous siblings, many foundational Black feminists and abolitionists viewed their queerness as integral to their resistance; from the Combahee River Collective to Audre Lorde to Angela Davis, our trailblazing predecessors knew the importance of centering queerness in the fight for prison abolition, and centering prison abolition in the fight for queer liberation.

Solidarity between queer folks on the outside and those currently or previously incarcerated is critical. Efforts like the Black and Pink, the Queer Detainee Empowerment Project, LGBT Books to Prisoners, and Survived and Punished all work towards accessing better living conditions for queer and trans people in prisons, towards freeing our community members, and towards creating a world where the abuses inherent to policing, prisons, surveillance, and punishment are no longer possible.

We need to follow in the footsteps of Black queer feminist abolitionists and not allow our celebration of queer pride be diverted from the radical and transformational intentions our community has had for centuries. Pride means liberating ourselves and each other from the systems that oppress us. Pride means resistance.

Jay Jones (22Ox, 24C) is from Tallahassee, Florida.

Jay Jones (they/them) (22Ox) is from Tallahassee, Florida, planning to major in the humanities or social sciences. They are involved with queer, feminist, abolitionist, and anti-capitalist organization (including OxSPEAR and OxPride) and are always looking for more ways to transform themself and their community. Jones enjoys graphic design, mutual aid and spending time with their four dogs at home.