Sometimes it is only safe to be queer in the most subtle of ways, with a hint of clothing or a phrase thrown into conversation. Depending on your location, the people around you and the time period you lived in, your own queer expression may have to look quite different from an Atlanta Pride Parade. In Gustave Caillebotte’s case, it is presumed by many art scholars that he expressed and hinted at his queer identity in the only way he could: through his paintings.

Caillebotte was one of the preeminent French painters of the 19th century and ran with the likes of famous impressionists such as Claude Monet and Pierre-Auguste Renoir. As a lesser-known impressionist, Caillebotte combined techniques like natural lighting and distinct perspective with a more realistic, academic approach in line with the ethos of the Académie des Beaux Arts in Paris. Caillebotte played an important role in the impressionist movement; outside of creating art himself, he funded exhibitions, bought art and even paid Monet’s rent at one point.

The preservation and advancement of European impressionism at that time can thus be credited partially to Caillebotte, as his expansive art collection became the center of the Musée d’Orsay’s impressionist collection after his death. Some even claim that Caillebotte changed art history.

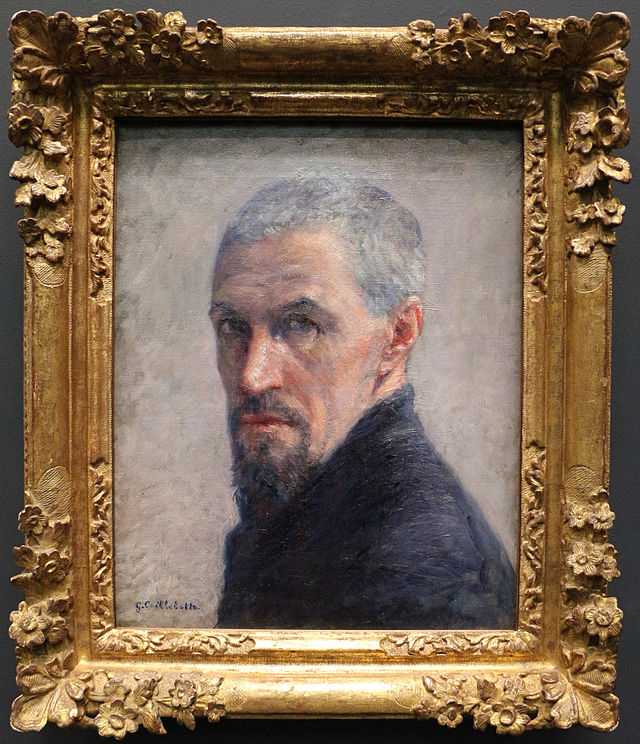

Self portrait of Gustave Caillebotte, ca. 1889. Musee D’Orsay, Paris. (Wikimedia Commons)

You may ask yourself, “Why is it so important to ask if Caillebotte was queer?” I think the best answer I have seen to that question is from an essay by Jim Van Buskirk, a queer writer and public speaker, in which he quotes Emmanuel Cooper’s 1986 book, “Sexual Perspectives: Homosexuality and Art in the Last 100 Years in the West”, where he states:

“The knowledge that an artist was or was not homosexual is not intended to ‘explain’ their work nor is it to suggest a particular context in which to view it. It is, rather, the start of a process to look again and recover what has traditionally been omitted from the history of art using this to inform the present.”

While there may be no undeniable written evidence of Caillebotte’s queerness, a glance at his oeuvre and a quick discussion with LGBTQIA+ viewers will have you seeing the story very differently. In that vein, Arthur C. Stone Jr. in his unpublished 1990 essay, “The Invisible Male, or Gustave Caillebotte Gets Sexy” asks the reader to follow art historian James Saslow’s advice to “trust your eyes: the gay viewer is usually far more open to suggestions of gay emotion than the art ‘experts.’”

Re-examining the work and life of Caillebotte does lead us down a path of queer exploration. First, take his subject matter: almost entirely men, and not just any men, but muscular rowers, suave suits, strong workers and nude bathers. If you look at the popular nude portraits of the time, you will note that the majority of subjects are women, but if you look at Caillebotte’s most famous nude, “Homme au bain,” it is a private and quotidien portrayal of a muscular man. The painting itself was completed on a grand scale, usually a size reserved for royal heroic portraiture, whereas this artwork depicts a truly intimate scene. Caillebotte shows his mastery of juxtaposition here, as viewers are let into this private moment in the bathroom, but the man also turns his head to one side, remaining anonymous and pushing the viewer away.

Another prime example of Caillebotte’s potentially queer appreciation of the male form is his famous Raboteurs de parquet painting. It again features the shirtless, muscular strength of working class men, this time as they scrape away at an old floor. Their faces are once again turned away from the viewer, making this public artistic display still seemingly private; there is at least some part of these paintings’ subjects hidden from the viewers, while also revealing quite a lot of the workers and their environment.

Gustave Caillebotte, “Les raboteurs de parquet.” 1875. Musée D’Orsay, Paris.

Caillebotte’s paintings of public life allude to a similar queer lens, but without using as much nudity. In Caillebotte’s “In A Cafe,” all the central figures are men, unlike the many cafe scenes featuring female and male couples painted by Caillebotte’s peers. Caillebotte’s artworks that did include women are often public scenes and sometimes even allude to non-heternormative standards in their own right. For example, take one of his most famous paintings, “Paris Street; Rainy Day,” in which you can see pairs of not only male-identifed and female-identified people, but also single men and women, coupled men and coupled women. Even if this might be subtle, there is still a hint at open sexual and romantic relationships between all people. Considering this was painted in 1877, there is something inherently queer about pushing those boundaries.

Gustave Caillebotte, “Paris Street; Rainy Day.” 1877. Art Institute of Chicago. (Wikimedia Commons)

Due to the social stigma of the time, Caillebotte could not have expressed his possible queerness as we do now, and even with that in mind he was still shunned by most family members and never married, possibly because he lived as a closeted gay man in 19th century France. Oftentimes the queerness of most things, from artworks to iconic songs to fashion trends, comes from the eye of the beholder, and I ask you to not ignore an important queer lens when looking at the famous artworks of Caillebotte and other art historical icons. Understanding and embracing the perspectives of both LGBTQIA+ artists and diverse artistic patrons can transform our experiences in museums, galleries, and in our everyday encounters with media, making them richer, more unique and more honest.

Zimra Chickering (24C) is from Chicago, Illinois.

Zimra Chickering (24C) is a born and raised Chicagoan who studies art history and nutrition science. She is also a student docent for the Michael C. Carlos Museum, Woodruff JEDI Fellow, educational committee chair for Slow Food Emory, and Xocolatl: Small Batch Chocolate employee. Zimra loves cooking, visiting art museums, photography, doing Muay Thai, drinking coffee, and grocery shopping. She uses writing as an outlet to reflect upon issues and oppurtunities within artistic institutions, and the unique ways in which food and art can act as communicators of culture.