On July 26, 1971, three astronauts embarked on the Apollo 15 lunar mission. The spaceship landed on the moon four days later, becoming the fourth successfully-manned moon expedition. Twelve days after launch, Apollo 15 splashed down in the Pacific Ocean.

Aboard the longest crewed Apollo mission at the time was Commander David Scott, father of Senior Lecturer in Sociology Tracy Scott. David Scott is one of 12 people to have walked on the moon and among the four still alive.

Apollo 15 Commander David Scott (left), Command Module Pilot Alfred Worden (middle) and Lunar Module Pilot James Irwin (right). Photo courtesy of NASA

Before Apollo 15’s launch

First serving as a Colonel in the United States Air Force, David Scott was later a pilot on Gemini 8 with Neil Armstrong in 1966 and the command module pilot on Apollo 9 in 1969. However, his largest extraterrestrial responsibilities were as commander of Apollo 15, tasked with overseeing the whole flight and landing on the moon, his daughter Tracy Scott explained.

Gemini 8 Command Pilot Neil Armstrong (left) and Pilot David Scott (right). Photo courtesy of NASA

The historic accomplishment did not seem “that extraordinary” to then 10-year-old Tracy Scott. Her father was accepted into the NASA program when she was four years old, so she grew up in one of three communities inhabited by astronauts and NASA employees outside the NASA Johnson Space Center in Houston.

During conversations about the launch with her father, Tracy Scott recalled how he emphasized the scientific novelty of the science experiments he would conduct and the stay on the moon overnight.

Although Tracy Scott’s social context contributed to her viewing her father’s occupation as ordinary, she could understand its significance “at a certain level” due to the media’s interest.

Apollo 15 space vehicle directly after launch. Photo courtesy of NASA

Using donated Scott family papers, University commemorates Apollo 15’s 50th anniversary with immersive learning hub

On the moon

Apollo 15 was the first extended scientific lunar mission, staying on the moon for just under 67 hours — nearly double the time of any previous Apollo mission. The mission was the Apollo expedition first to have three extravehicular activities (EVA), or astronaut pursuits outside of the spaceship, comprising over 18 hours.

The initial moon landings were shorter because the U.S. at that time was more motivated to beat the Soviet Union in the space race rather than to conduct scientific experiments, Tracy Scott explained. However, after problems including the explosion of an oxygen tank on Apollo 13, NASA reoriented their goals to be more scientifically ambitious.

Apollo 14 was already planned as a short mission by the time NASA changed objectives, so Apollo 15 was the first lunar mission to have a pioneering scientific purpose.

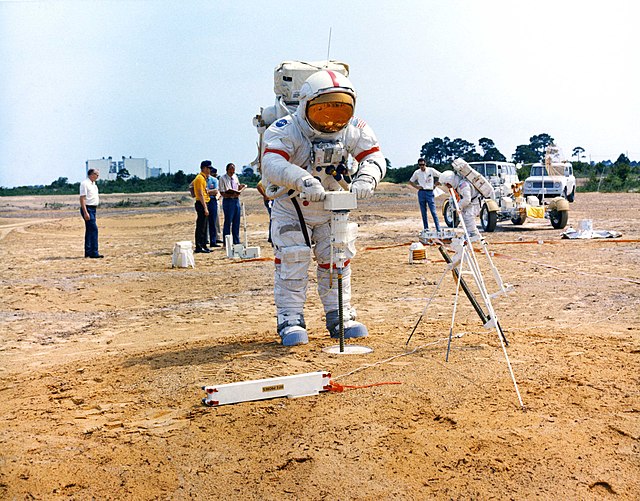

David Scott engages in geology training ahead of the Apollo 15 mission. Photo courtesy of NASA

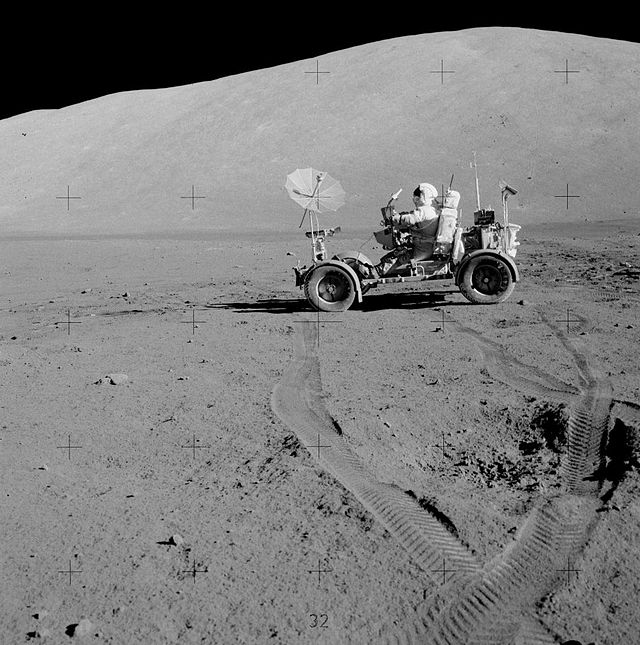

Consequently, NASA introduced new information-gathering technology like the lunar rover on Apollo 15 and extended the mission’s geology and scientific experiments components.

David Scott on the lunar rover vehicle. Photo courtesy of NASA

Under NASA’s reevaluated mindset, David Scott could test a 16th century theory during the third EVA.

In 1589, astronomer Galileo Galilei dropped two spheres of different masses from the Tower of Pisa, both hitting the ground at the same time. He thus predicted that under the same conditions and negligible air resistance, gravity causes all objects, regardless of mass, to fall at the same rate.

With a feather in his left hand and a hammer in the right, David Scott set out to test the prediction on the moon, a naturally vacuous space due to its incredibly thin atmosphere.

“One of the reasons we got here today was because of a gentleman named Galileo … who made a rather significant discovery about falling objects in gravity fields,” David Scott said while on the moon. “We thought, where would be a better place to confirm his findings than on the moon?”

David Scott then released both objects from his hands simultaneously and observed the feather and the hammer hit the moon’s surface at the same time, upholding Galileo’s prediction.

After Apollo 15’s return to Earth

Apollo 15 crew on retrieval ship U.S.S. Okinawa after splashing down in the Pacific Ocean. Photo courtesy of NASA

Tracy Scott’s most memorable experience from the expedition came after the spaceship’s landing when she dined at the White House and spent a weekend at Camp David.

While the parents ate downstairs, the children of the Apollo 15 astronauts ate upstairs in the private living quarters and were chaperoned by Kim Agnew, former U.S. Vice President Spiro Agnew’s daughter.

The children finished eating before the parents, affording them time to wander the private living quarters. After the parents finished eating, former President Richard Nixon took the families on a private tour of the White House.

“It was all aimed at us kids,” Tracy Scott recalled. “He took us around and showed us secret passageways and all these different interesting facts about the White House and the rooms that we were going into.”

The families left the White House via the presidential helicopter, which flew them to Camp David for a weekend of bowling, swimming and golf cart driving.

Growing up in early NASA era, as the child of an astronaut

Being the child of an astronaut in the early NASA era meant growing up in one of three small communities composed of other astronauts or NASA employees, which LIFE magazine dubbed “Togethersville” in 1968. For Tracy Scott, this meant becoming best friends with others whose life was similar to her own in what she calls a “very close-knit” community.

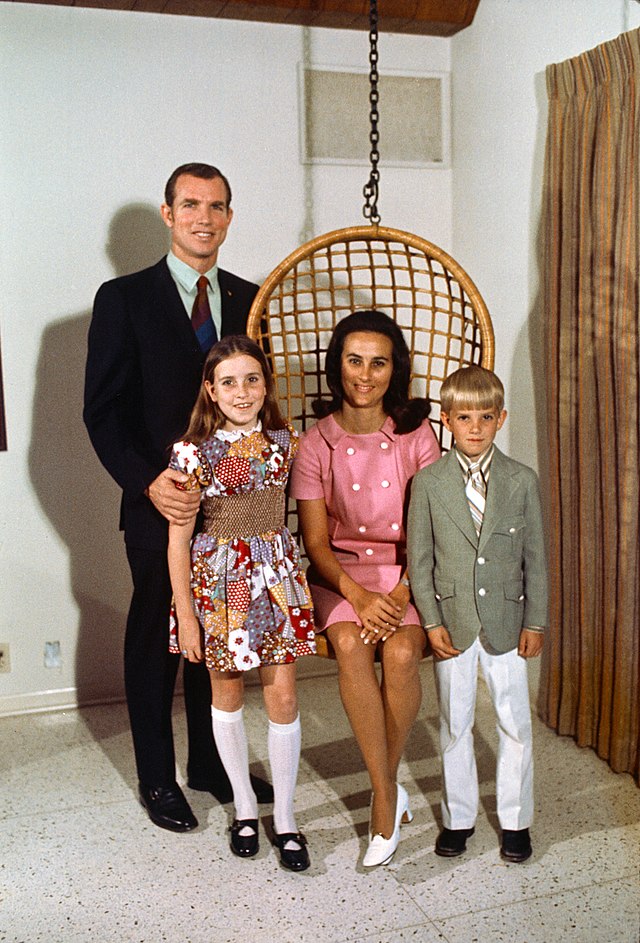

From left to right, David Scott, his daughter Tracy Scott, first wife Ann Ott and son Douglas Scott in April 1971, about three months before Apollo 15’s launch. Photo courtesy of NASA

Tracy Scott’s best friend was Diane Gordon, who lived across the street from her and whose father was on Apollo 12.

Likewise, Tracy Scott noted that the moms became close. Her mother was really close with Apollo 11’s Command Module Pilot Michael Collins’ wife. The “moms would kind of switch who made dinner” and they ate together often, Tracy Scott said.

Tracy Scott has two distinct memories about her father’s occupation that captured her attention: photographs and NASA simulators.

“That was a way into what he was doing, through looking at photographs from NASA, and thinking about how amazing this was by looking at the visual images,” Tracy Scott said.

The simulators at the space center also helped her appreciate her father’s job. Configured to look like a spaceship, the simulators were meant for training purposes, but she was permitted to sit in the device, peeking into her father’s world.

While living in these NASA communities allowed children to experience an enhanced perspective on the extraterrestrial realm, Tracy Scott said the limited social scene also made the towns isolating. She noted that those who left the area often faced “a much more rude awakening.” For Tracy Scott, that came when she moved to California in seventh grade.

“It was really hard because I was put into this context where I was the oddity; people knew my dad and they were kind of starstruck,” Tracy Scott said. “Girls in middle school when they first met me wanted to be my friends so that they could talk about this stuff and meet my dad.”

In high school, she said she didn’t want to tell anybody about her father because she wanted her peers to like her for who she was, not because her father walked on the moon.

David Scott standing on the moon. Photo courtesy of NASA

“It took a while to get to a point where I was comfortable with that and realized people would be interested and have a lot of questions at first, but that wasn’t the only thing they cared about if they really were my friend,” Tracy Scott said.

Looking back on Apollo 15 and her childhood 50 years later, Tracy Scott said she now sees more of the sociological significance of the early NASA era, not just the scientific importance. This includes putting everything, including the science, into the context of the time, Tracy Scott added.

Today, there is no rocket that can carry people to the moon. Since 1972, no human has been sent outside the Earth’s orbit, meaning that humans have been going up about 250 miles above Earth, while people between 1969 and 1972 went about 250,000 miles above Earth to the moon.

“Think about what we accomplished given the technology of the time,” Tracy Scott said. “The onboard computer, it held like nothing, so a lot of what the guys had to do was memorize all of the stuff. They had to be the computers in their heads.”

Editor-in-Chief | Matthew Chupack (he/him, 24C) is from Northbrook, Illinois, majoring in sociology & religion and minoring in community building & social change on a pre-law track. Outside of the Wheel, Chupack serves on the Emory College Honor Council, is vice president of Behind the Glass: Immigration Reflections, Treasurer of Omicron Delta Kappa leadership honor society and an RA in Dobbs Hall. In his free time, he enjoys trying new restaurants around Atlanta, catching up on pop culture news and listening to country music.