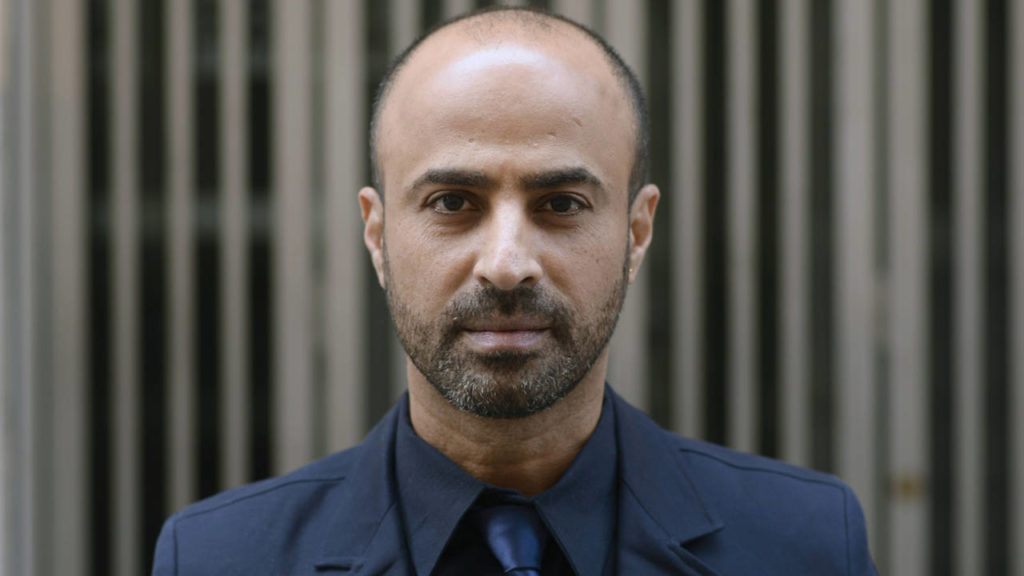

Courtesy of Efe Efe/Nacho Gallego

A young man survived a near-death stabbing. An openly gay council member received death threats. A Palestinian crossed the border weekly to perform in drag before fleeing the country. Those are narratives surrounding WorldPride Jerusalem 2006, the first LGBT pride parade in Jerusalem, in film director Nitzan Gilady’s 2008 documentary Jerusalem Is Proud to Present.

Gilady’s film also explores another perspective. The ultra-Orthodox Jewish community rejected hosting a pride parade in the Holy City, and the Jerusalem Open House faced violent discrimination in its attempt to find acceptance. Gilady interviewed people on both sides of the conflict to provide a holistic representation of the historic event.

Similar to many of Gilady’s films, Jerusalem Is Proud to Present follows tensions between groups with conflicting ideologies, in this case, the Jerusalem Open House and others who support equality regardless of sexuality as well as religious groups that condemn non-straight individuals. The April 5 screening was the penultimate event in a series of Gilady’s work, hosted by Emory’s Department of Film and Media Studies. Gilady teaches National Cinemas, Israeli Documentary Film at Emory this semester. The final screening will feature Gilady’s 2012 film Family Time April 12 at 7:30 p.m. in White Hall.

This transcript has been edited for clarity and length.

Naomi Keusch Baker, The Emory Wheel: How did you first get into making films?

Nitzan Gilady: My original [plan] was to become an actor. After the [Israeli] army I moved to New York and studied theater at Circle in the Square [Theatre]. I was sure that I [wanted] to be the next Robert De Niro, but reality was different. When I auditioned, [I was always cast as] a terrorist, unfortunately. I’ve always fought against stereotypes, so I knew that America [was] not going to be a place for me to pursue my dream to become an actor so I moved back to Israel. At that time, I shared an apartment with one of my best friends, Mili Avital. Before she became a famous Israeli actress, I bought this camera and was playing with it as if we were making a documentary about her. When I went back to Israel and she [became] famous, we approached the TV commercial channel to make a film about her. I had never studied film, [but] they didn’t care about my experience.

EW: Do you feel your personal experiences impact your work or do you try to stay objective?

NG: It’s hard to stay objective. [In Jerusalem Is Proud to Present], I showed people who were against and for making the parade in Jerusalem, but you could [infer what] my take on the whole idea [was]. If it doesn’t move [me], I wouldn’t make a film about [it].

EW: When you’re making a documentary about a contentious subject and you want to interview individuals or follow the story of a family, how do you ask them to take part in your project?

NG: You need to find out who you want to talk to [and] how to approach them. I reached one character through the newspaper. I explained what I wanted to do and he [immediately] agreed. When I met the Yemenite Jewish people that were brought by Satmar representatives, it was difficult to convince them to do the film. I flew from Israel to New York to meet them and they shut the door in my face. I put [on] a yarmulke because they’re religious, to connect to them. [We] had to get to know [each other]. You have to find people that understand they [will] gain from telling their story.

EW: How did your experience from making In Satmar Custody impact the making of Jerusalem Is Proud to Present?

NG: It’s always a fresh start. I don’t think there is influence from a film to a film. It’s hard to find a good story. For example, I don’t think I’m going to make a film like In Satmar Custody again because it’s a specific story. When we filmed Jerusalem Is Proud to Present, we thought [the filming was] going to be one year because we knew [the parade was] in six to eight months. Who could have guessed we were going to have a war and they were going to postpone it. Then the film [required] three years. Every time you start a [documentary], you don’t know where it’s going to take you. I’m shocked that Family Time was made because [my parents’ consent] wasn’t planned. Every film is like a child and has its own characteristics.

EW: Since your films are about Israel and Jewish people, do you intend to continue this pattern or are there other subjects you want to explore?

NG: I’m interested in the fringe, in subjects that need to be voiced that we [don’t] hear. My [family is] Jewish Yemenite, so I think I got my sensitivity from being different. [My differences] made me more aware of [minority groups].

EW: Your films have been shown all over the world, including the Atlanta Jewish Film Festival, and you’ve earned international recognition. What kind of feedback have you gotten from viewers and people in the film industry?

NG: I was very lucky. Wherever I [went they were] well received. [They have] been in hundreds of film festivals so the reaction was always very positive, but you’ll always have someone who criticizes your work. I like traveling and having a [question and answer session] afterward because it creates [discussion] about the subject.

EW: While the reactions have been mostly positive, people connect to your films in different ways. For you, what is the main purpose of Jerusalem is Proud to Present?

NG: That was the first film [in which] I dealt with [being] in the closet until the age of 35 because [it was] a subject I was so afraid to deal with. I [had many] questions about [pride parades] because I was closeted. I was afraid about how my family [would] react to [the] film. One of the reasons I have characters on both sides was [so] my father [would] watch it and connect to it [by hearing] his opinion: parades shouldn’t happen. I wanted to show the variety [of] opinions about making a pride parade in Jerusalem. You can be with the character who represents your opinion but see the consequences [of taking] your opinion to an extreme place. You can have your own opinion, but know the limit. You cannot lose your humanity.

EW: How was the process of filming your family in Family Time different from filming people you didn’t know before?

NG: It was the hardest thing. I lost the tools of the director because at times I felt I [was] harming my family. I would stop the camera because I thought [I was not showing] my family in a positive way. It was the hardest film I’ve ever made because I was their son. I needed to protect them, but in order to understand the characters, you have to paint the whole picture.

EW: What does your family think of the film?

NG: They love it. It was a surprise because they were closeted [about my identity] even after I came out to [them]. I worried for almost two years when we edited the film. It’s a film [about] this conversation you want to make with your parents but you’re afraid to. Normally I’m courageous, but with them it was hard. At the end, I was happy they [gave] me the opportunity to film them. You could see how much love they have for [me]. Even though my father had a hard time, he agreed [for it] to be on TV and be shown all over Israel.

EW: For students at Emory who want to use art to explore social issues like you do, what kind of advice do you have for starting?

NG: Follow your dream. With acting, I gave up and I [don’t] know what would have happened, but if you want something, go for it. I got so many rejections [in] filmmaking. I have a pile of letters of “no, no, no, no” for scripts that I wrote, but the “no” was a step. It was hard, but after a while, it was just a step to go higher and higher. Listen to yourself. Know your talent and follow it. Never give up.