In a summer 2022 advertisement for grocery delivery app Instacart, singer Lizzo is laying in a bathtub. She wishes for various items, selects them in the app and watches them appear in larger-than-life form. First, she selects cherries, which rain down from branches that have appeared above her. She next selects ice cream and watches as a drawer flies open to reveal a massive spoon with a giant scoop of ice cream. She selects a baguette and her room is transformed into a french bakery storefront, all while she remains in her bathtub. And so on.

There is nothing about this commercial that stands out against other modern ads like Mountain Dew’s “Puppy Monkey Baby,” Mio’s “Nose Job” or Skittles’ “Princess.” But, when compared with, say, TV commercials of the ’40s, the Lizzo ad is unmistakably surreal. Advertisements 80 years ago made a rational argument for the unique benefits of their particular product, while advertisements today embrace the world of feelings and associations in all its zany and surreal forms.

A similar pattern of increasingly surreal filmography is visible everywhere from political campaigns to social media. However, this consumerist surrealism that suffuses our 21st century lifestyle feels less potent than the original movement. Ads, political campaigns and the like may engage the world of dreams, but they do so in order to push something, to get in your head.

To understand the growing presence of consumerist surrealism, consider the unconscious. Theories advanced by Sigmund Freud in the early 20th century introduced the concept of an unconscious as a hidden but fundamental part of the human psyche. Freud’s insights quickly expanded beyond their academic and psychiatric origins. In art, the surrealist movement was formed with the goal of creating art that targets the unconscious. Pioneers of modern advertising like Edward Bernays incorporated psychoanalytic insights into ad campaigns. Because surrealism is the artistic tool most strongly associated with the unconscious, advertisers since Bernays have embraced it to pursue their commercial goals. The massive growth in zany but targeted advertisements over the course of the 20th century has obscured the moving power of surrealist films when they explore the unconscious on its own terms, without a business or political purpose.

As an antidote, I prescribe the marvelous world of animated short films. These shorts have an uncanny ability to instantly tap into the untamed currents of the psyche, unbound by reason. They defy explanation and yet make perfect sense.

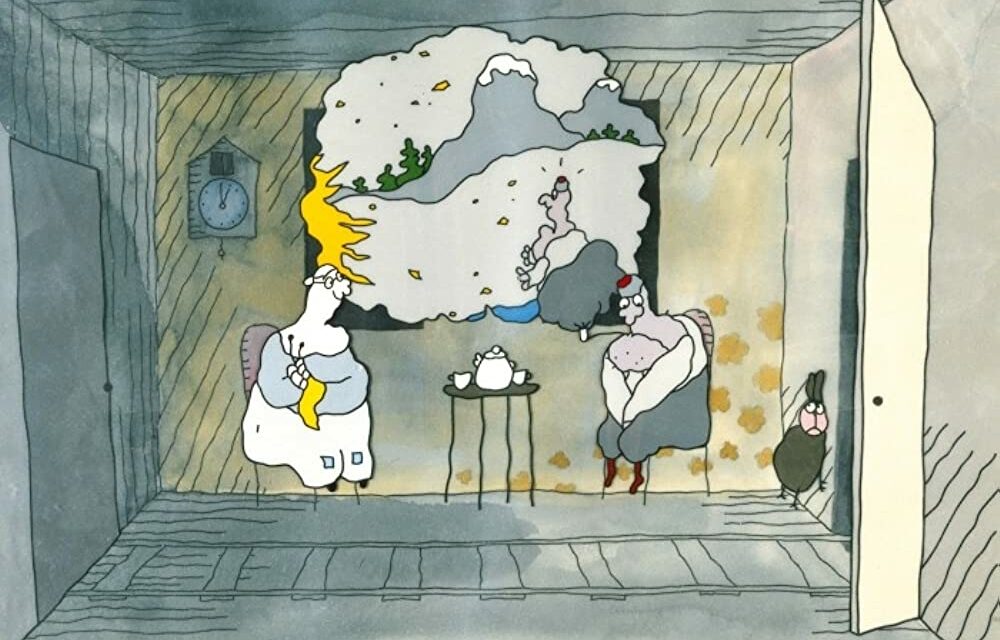

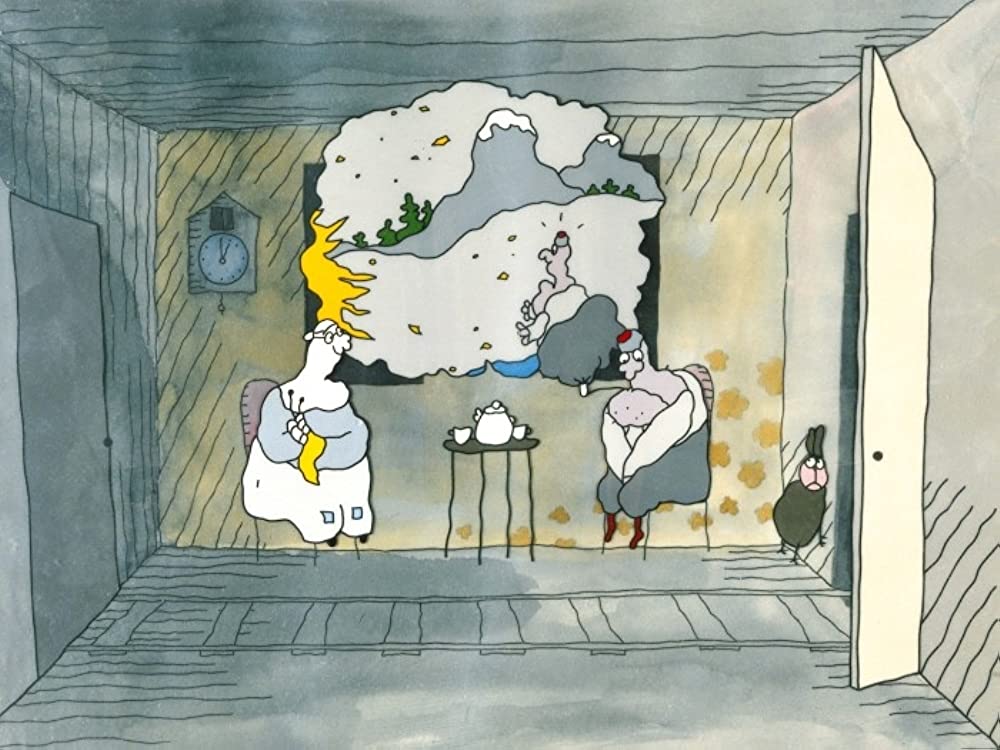

Take for example the Dutch film “Home on the Rails,” directed by Paul Driessen. It follows a husband and wife whose house lies directly atop railroad tracks. At regular intervals a train passes through their house. Several details in the film defy comprehension. The characters briefly disappear every time they go to open the door. The cuckoo clock which notifies the couple when the next train is coming follows its own incomprehensible logic. Despite all this, the pieces of the short fall perfectly together and watchers may find themselves inexplicably shedding a tear at its tragic end.

Courtesy of IMDb and N.I.S.

For something with less plot but just as much intrigue, look no further than Ivan Maximov’s “5/4.” The film showcases a myriad of beautifully surreal characters, doodles come to life, all set to the smooth tunes of Dave Brubeck’s “Take Five.” Or, consider Don Hertzfeldt’s short film “The Meaning of Life,” a labor of love of which Atlanta Journal-Constitution critic Bob Longino described as “reaching deep to conjure up thoughts about the nexus of existence.” The film is weird, alien, random—in other words, surreal. But, that does not damage its beauty; indeed, it is precisely what makes the film so moving.

Short films are also adept in their ability to infuse other forms of art with a surreal whimsy. For example, the Canadian film “Pas De Deux,” directed by Norman McLaren, takes inspiration from the dance duet technique for which it is named. The video features one actor technologically transformed through a set of lagged loops, challenging the boundaries between live action and animation. The result is a dazzling display that is inexplicably affecting.

In the world of visual art, director Aleksandr Petrov’s animated adaptation of “The Old Man And The Sea” feels like an oil painting come to life. It was made using the mesmerizing paint-on-glass technique. The Oscar-nominated Japanese animation “Mt. Head,” meanwhile, has its roots in the Japanese rakugo style of storytelling. The music and narration are haunting, the story is fantastical and the ending is excellently absurd.

Surrealist videography is all around us in commercial and targeted forms, and that oversaturation makes it easy to lose sight of its unique value. Yet the numerous animated short films from around the world is a reminder of how transformative animation and all its surreal characteristics can be.

Sam Shafiro (he/him) (25C) is a Political Science major from Oak Park, Illinois. He is involved with the Emory Barkley Forum for Debate, Deliberation, and Dialogue and the Emory SIRE undergraduate research program. In his free time, Sam enjoys bananas and celery, as well as other fruits and vegetables.