(Jessie Satovsky/Staff Illustrator)

Not many people can say they are in the top 0.057% of anything, but Prithu Gupta (27C) can.

According to the International Chess Federation (FIDE), a person can achieve four titles in the game: Candidate Master, FIDE Master, International Master and Grandmaster. As of 2021, FIDE declared that only 1,742 people hold the title of grandmaster, and Gupta is one of them.

Emory University Chess Club President Blake Liu (25C) explained that in every game, one has the potential to play like Magnus Carlsen, FIDE’s current world No. 1 player, but because chess is such a difficult game, most everyone makes errors.

“A lot of students of the game that have studied for decades will never become even within one standard deviation of becoming a grandmaster,” Liu said.

Gupta first stumbled upon chess at nine years old on his way to school in Gurgaon, India. A group of kids played every day before class. Eventually, Gupta joined a few games and then became a regular in the morning group. He played on Sundays with his father, but he said that it was more fun to play with kids his own age.

A month later, Gupta decided chess no longer fit into the category of a hobby — it became an obsession. He said his formal training first began with reading chess strategy guides. Gupta’s interest in these books started with “Grandmaster Repertoire,” a series about chess openings consisting of over 15 textbooks.

“Openings were a highlight in my preparation because if I were to get into a bad position in the opening phase of the game, there could be no way I could go on to even possibly save half the points later on,” Gupta said.

His first chess tournament was in Delhi, in 2013, when he was nine years old. Gupta had only been seriously training for a few months at the time. Players that aspire to achieve a high level of chess are usually introduced to the game by the time they are between five or six years old, and on average, obtain the title of International Master by 15 years old. Gupta entered the game later than his competitors, but said he was “really excited to be there.”

To earn an official FIDE rating, one has to score points against other rated FIDE players. Gupta achieved that, but his rating after that tournament was much lower than his coach had hoped.

“My first coach back then was skeptical of me getting such a low rating at first, because it was naturally going to be very difficult to build upon that and increase from that, but I was probably the happiest person in the world to have achieved that,” Gupta said. “I gained quite a lot of rating points in my subsequent tournaments till the end of 2014, so I was really motivated.”

With this attitude, Gupta’s win streak and rating progressed linearly. As he advanced, his training intensified, and his schoolwork became more rigorous. Gupta said he would practice seven days a week and would even bring a small chess board to school to rework positions during breaks or class.

Vardaan Nagpal, Gupta’s good friend and an international master, said they attended school only about 30% of the time and spent six months out of one year in Europe. FIDE tournaments were offered in India, but Nagpal said the tougher tournaments tend to be in Europe.

Gupta was selected to train under Vladimir Kramnik, the undisputed world chess champion from 2006 to 2007, for 10 days in Geneva in 2019. Four months later, Gupta returned to Europe to train with Boris Gelfand, another chess legend known for his unique playing style of calculating moves that weren’t always found in a textbook.

Reflecting Gelfand’s technique, Nagpal characterized Gupta’s playing style as aggressive. However, Nagpal also noticed that as Gupta neared the title of grandmaster, he became increasingly stressed. At this point, Gupta was studying up to 15 hours a day before tournaments.

“The amount of effort he’s put into it, I could never do it,” Nagpal said. “He definitely put twice as much effort as me in everything at any given point in time. I didn’t really know a lot of people who were able to do anything at a stretch for eight or ten hours like he used to do.”

To achieve the title of grandmaster, a player has to meet two qualifications. The first is earning an Elo — a rating system of a chess player’s estimated skill level — of at least 2,500. The current highest recorded Elo score is 2,882. Secondly, the player must have three favorable norms against other grandmasters from different countries, which is when a player scores more than one point above what is expected against another player.

After nine rounds in the 2018 Tradewise Gibraltar Masters, Gupta became an international master, and six months later, placed in the top 15 during the Biel Masters in Switzerland. Then, in the fifth round of the Portuguese League in 2019, Gupta beat International Master Lev Yankelevich, officially crossing the Elo threshold of 2,500. Despite a series of wins, his losses during critical games caused his rating to slip. To counteract this, Gupta said he was determined to work harder, studying more intensely than usual.

Gupta was scheduled to play three matches in Italy but became sick before the tournament, forcing him to withdraw. With almost two months of recovery, Gupta missed school and more matches.

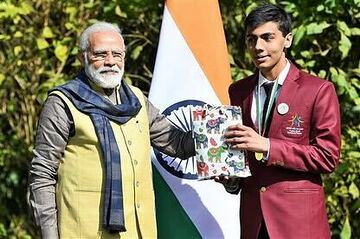

Prithu Gupta (27C) receives an award from Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi in 2019. (Courtesy of Prithu Gupta)

In April 2019, Gupta needed only 22 more rating points and one norm to become a Grandmaster. In the Reykjavik Open in Iceland, one of the most prestigious open tournaments in the world, Gupta beat a grandmaster with a 2,600 Elo in the third round. With that impressive win, the next game would decide if he could achieve his third norm. However, in this instance, Gupta’s aggressive style of play left an opening for opponent Nils Grandelius to take his bishop and force a seven-hour sequence. The match ultimately ended in a loss for Gupta. Shortly after that tournament, Gupta played in the Aeroflot Open in Germany, which was statistically one of the worst tournaments he’s ever had.

With training and being abroad so often, Gupta said he was “sacrificing everything.” He had no time for friendships because he was doing schoolwork when he wasn’t training. This was Gupta’s tipping point, and he considered walking away from chess and giving up his goal of being a grandmaster.

“I just really felt that I didn’t have it in me,” Gupta said.

However, after encouragement from his parents and coaches, Gupta continued to pursue his goal. He was scheduled to play the Porticcio Open in Corsica, France in 2019. Gupta was reluctant to go, but tried to focus on enjoying each game, instead of the result. With this mindset shift, Gupta began winning games again and gradually rediscovered his interest in chess.

Ultimately, Gupta went on to achieve his final norm in that tournament and became India’s 64th Grandmaster, completing the 64-square chess board grid of Indian grandmasters that was started in 1988 when Viswanathan Anand became India’s first grandmaster.

Sixteen countries and a college acceptance letter later, Gupta said he plans to keep learning off the board.

“In whatever way life has transpired over the course of the last three or four years has only been for the better and now the best,” Gupta said. “I’d honestly have it no other way.”

Sasha Melamud (she/her, 27C) is from Clearwater, Florida, planning on majoring in creative writing and spanish. In her free time, Melamud enjoys being out in the fresh air, fitness, and hanging out with friends.