Art offers the unique opportunity to create something entirely new, often literally starting from a blank canvas. Artistic production is also a fairly forgiving process; the failure of early works in a particular time does not necessarily lead to the subsequent failure of later works in a different time. If it did, the names Vincent van Gogh and Claude Monet would mean very little to us today.

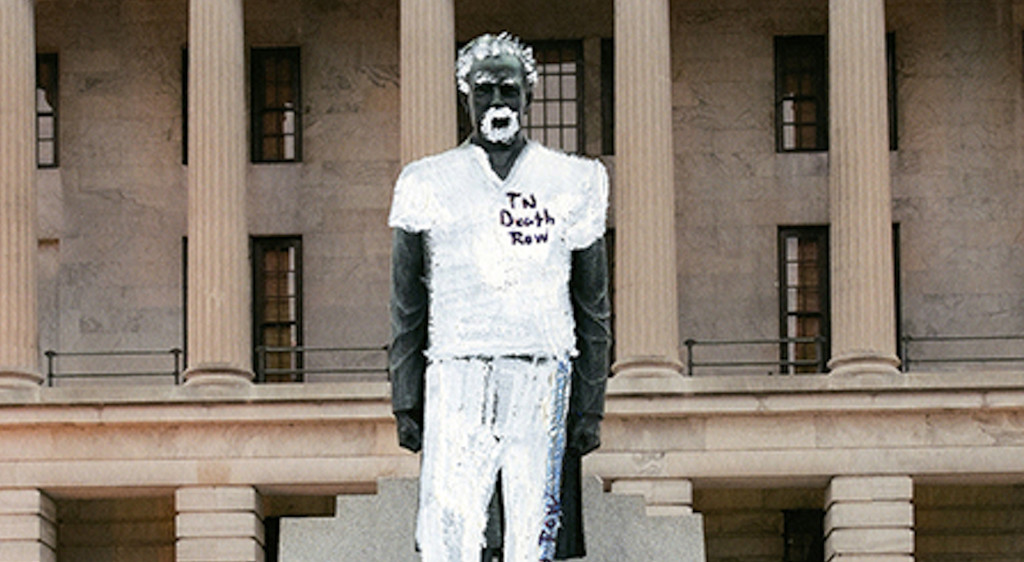

“The Life After Death and Elsewhere” exhibit organized by Robin Paris and Tom Williams in New York City, on display from Sept. 10 to Oct. 24 explores the artistic responses of inmates at the Riverbend Maximum Security Institution in Nashville, from the time they arrived to their impending executions.

Visual art is especially unique because it allows a separation between artist and artwork that is much harder to achieve in other mediums, such as performance art or film, where the performer or actors directly confront the audience. For a great deal of art, including ancient art in the Americas and Africa, the artist’s identity is not known (or even considered important). This anonymity and dissociation between artist and artwork may be particularly appealing to people who fail to meet social norms and expectations.

While the inmates included in this exhibit have histories that are impossible to forget, it is easy to dissociate these histories from the artwork. The works range from pencil on paper drawings to mixed media sculptures and videos. Although each inmate addresses the same fate, the works are remarkably diverse ranging from political protests against the death penalty to personal narratives on how they coped with challenging prison conditions.

One of the most striking pieces in the exhibit is a large-scale model airplane created by Ron Cauthern out of cardboard. Red and lime green sinuous lines meander naturally across the jet-black surface of the plane, evoking the image of Cauthern’s blood that, at least for now, flows freely through his veins. Cauthern adorns the top of his plane with bright red and orange flames that appear to reach longingly for the cockpit, however, no pilot is visible.

These flames evoke a sense of fear in the viewer, and I know I certainly would not want to board this airplane. Similarly, Cauthern is not “on board” with his upcoming execution. He further emphasizes this with the ominous white skull that he places underneath the plane’s propeller. Cauthern makes it even clearer, stating in a brief letter that “It’s simple, nothing good can be born out of a life for a life, except more victims.”

“Airplane” seems overtly political when viewed in the context of the exhibit and accompanied by Cauthern’s letter. However, without these clues, the artwork could have been created by anyone. The flame and line pattern on the plane’s surface recall Hot Wheels toy cars, pointing to the design for a children’s toy. With the menacing skull on the front, the work could also easily be a decoration for Atlanta’s own Vortex restaurant. If displayed in a more traditional art gallery, the viewer would have no way of knowing Cauthern’s criminal history from the artwork. Rather than highlighting the flaws of the artists they display, traditional art galleries elevate them. The description of a Gauguin painting will likely discuss his travels to Tahiti but exclude his fiery temper.

The organizers of the exhibit attempted to endow it with a very specific meaning: that the artists on display are, according to their website, “more than merely convicts condemned to execution.” While viewing these works separately from one another or imagining the alternative places they might be displayed at might allow a separation of artist from artwork, but the context of “Life After Death and Elsewhere” prevents that. In presenting the works in a gallery exclusively for inmates, the organizers, perhaps unintentionally, pigeonholed those inmates as criminal artists rather than as artists who are also criminals.

Yet the connection between artist and artwork is necessary for the viewer to understand the political implications of many of the works included. Some artists offer pleas for social recognition and others address the unsatisfactory prison conditions they face. Akil Jahi created a large cardboard shoe modeled after those included in his prison uniform — in a way, escaping his confinement through his art.

Other artists such as Gary Cone also created works that express their desire to escape the harsh reality of prison. Cone’s “Reading Has Been My Way to Exit” is a spiraling column made from books that consoled him during his years of confinement, including works by Anne Carson, William Faulkner and Herman Melville.

“Life After Death and Elsewhere” powerfully conveys the complexities in understanding a piece of art for both its formal qualities and its qualities as an object created by a human with a unique history. When viewed objectively, these works can be appreciated as sculptures, paintings, photographs and videos. When viewed contextually, they draw attention to the startling reality faced by both prisoners and others who are also stigmatized by society. In order to fully understand the exhibit, however, the works must be approached from both of these perspectives simultaneously.

Artist Harold Wayne Nichols accurately summarized these complexities in a letter accompanying his work in the exhibit: “If after looking at my works, all one sees is a death row inmate, or judges me solely on one act, one moment out of my life, would it be me that failed or the viewer?”