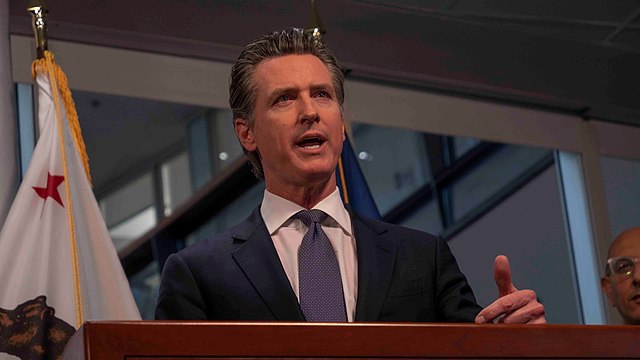

Wikimedia Commons / Office of the Governor of California

When I heard about rappers Gunna and Young Thug being arrested for alleged racketeering charges, I couldn’t help but think of the classic Key & Peele sketch, “Rap Album Confessions.” In the skit, Key, as a police detective, interrogates Peele, playing the fictional rapper “Gun Rack” for the murder of “Darnell Simmons.” The detective grows increasingly more frustrated as he plays lyrics to Rack’s album, titled “I Killed Darnell Simmons.” With each lyrical admittance of murder weapon, motive and location, Rack excuses himself by citing “artistic expression.”

Some prosecutors seem to have taken the bit seriously, citing lines written in fictional narratives as evidence for criminal activity. The blatant exaggeration of such cases involving hip-hop artists is what makes the sketch hilarious. Still, as courts use rap lyrics as evidence in criminal cases across the country, my smile has faded. Hip-hop has been centered in a discussion about artistic freedom and legal proceedings, and unsurprisingly, the community has been misrepresented. While some have painted the genre as a space to advertise criminal enterprises, in reality, the artists use music to reflect on their journeys to success.

Earlier this month, Governor Gavin Newsom (D-Calif.) signed a bill restricting the use of creative expression as admissible evidence in criminal trials. I would be confused about the utility of such specific legislation if similar cases had not resulted in the prosecution of artists from Snoop Dogg to Meek Mill for alleged violent crime. However, as more prosecutors move to include lyrics in criminal evidence, comparable bills like Newsom’s could be a necessary step in preventing such legal misuse of artistic expression. Since the nation was founded, free speech has been a priority. The precept needs to apply to hip-hop as it does any other m edia to avoid systemically advocating unequal legal treatment.

Although James Madison and George Washington were not bumping Meek Mill or Jay Z’s rap lyrics when they ratified freedom of expression to be protected by the Constitution, even many originalist judges have argued for safeguarding violent art under the First Amendment. Not only is the use of lyrics in proceedings a perversion of constitutional rights, but it is also a blatant double standard against Black artists.

The hip-hop community has been disproportionately affected in cases where art is used as evidence. Notably, other forms of art and entertainment are rarely applied to criminal cases. On this disparity, Run The Jewels rapper Killer Mike tweeted “White woman, Nancy Brophy wrote “How to kill your husband” she did kill her husband. The courts did not allow that to be used as evidence becuz of her 1st amendment right.” Mike is exactly right. Brophy was recently convicted of second-degree murder without using her essay as evidence. Additionally, I find it particularly confusing that hip-hop is so often derided as a crime-ridden genre when guitar legend Eric Clapton can write a song called “Cocaine” about his enthusiasm for the drug or the Beatles can pen “Lucy in the Sky with Diamonds” (LSD) with minimal backlash. This distinction in public and legal response against Black art is not a new phenomenon. Such a difference in reaction to Black versus white art is the reason that Fox News commentator Geraldo Rivera could notoriously claim that “hip-hop has done more damage to Black people than racism in recent years.” The disparity is deafening, and some forget that the Rivera quote was in reference to a Kendrick Lamar song with the chorus “We gon be alright.” Rivera’s ignorance is just one example of resilience being called harmful. Too often, Black positivity and resilience are misrepresented in media as violence and censored as a result.

Even outside of the courtroom, law enforcement has lambasted hip-hop artists. In 1989, N.W.A.’s “F— tha Police,” a fictional but violent song written in response to Los Angeles Police Department police brutality, led to the group’s music label receiving a cease and desist letter from the FBI. The agency noted that they believed that their views “reflect the opinion of the entire law enforcement community” and that “music plays a significant role in society.” They also said “advocating violence and assault is wrong” the same year Aerosmith released a song with the lines “What did her daddy do?//It’s Janie’s last I.O.U//She had to take him down easy and put a bullet in his brain.” Yet, Aerosmith received no FBI letter. One could argue that Aerosmith was violent but not anti-police. However, if the issue was not violence, but anti-police rhetoric, then we should see similar responses to white, anti-police musicians. Metal band System of a Down accused law enforcement of “pushing little children with their fully-automatics” on their song “Deer Dance” and still, no letter. In Francis Ford Coppola’s 1972 “The Godfather” movie, he even displayed the murder of a police officer by the Italian mob. If not for genre, I struggle to find differences between these representations of violence and the images displayed in rap. While one could accuse hip-hop’s detractors as unadulterated bigots, I choose to presume best intent; that hip-hop narratives are significantly misunderstood in the scope of American culture.

As contemporary Black art, society seems to consume hip-hop stories differently than other, more traditional art forms. The genre is a treasure trove of holistic and illustrative stories reflecting on decades of African American history. Historical fiction serves as a documentation of culture through the years, and hip-hop is no exception. Minimizing its impact both prevents a larger audience from recognizing its significance and undervalues the talent of its creators. The FBI is right; music plays a hugely consequential role in society. Yet, they are incorrect in the supposed intersection between artistic expression and subsequent legal action. A line exists between creative works and admissible evidence, and the American legal system should protect its creators. Society is in a dangerous state when the government can censor artists. Freedom of expression doesn’t discriminate, but a system that limits it does.

Ben Brodsky (25C) is from Scottsdale, Arizona.

Ben Brodsky (he/him) (25B) is from Scottsdale, Arizona. He has explored hip-hop history since 2019, first on his blog SHEESH hip hop, and now with “Hip Hop Heroes,” a series of essays on narrative in hip-hop. When not writing about Jay-Z, you can find him writing “Brodsky in Between,” an Opinion column on political nuance, graphic designing and playing basketball.