The concept of unconscious racism emerged in the late 20th century, but the theory has become more widely known in recent years. The creators of the term defined individuals who unconsciously discriminate as people who cannot separate cultural stereotypes and opinions from their actions when interacting with minorities, even when they see themselves as not racist, or even anti-racist. While unconscious bias was originally defined as affecting Black Americans, the idea has expanded to include the impacts on all people of color and religious communities. However, some groups — notably, Jews — have largely been left out of this conversation.

The flag of Israel flying in the sky. Zachi Evenor/ Creative Commons

Antisemitism, prejudice against Jews, is most comparable to discrimination based on race, since the perpetrators of antisemitic acts, historically, have seen one’s Judaism as genetic and unchangeable. However, antisemitism has generally been more explicit than some forms of racism. Alt-right marchers chanting “Jews will not replace us” are hardly subtle. However, in recent years, and especially since the Oct. 7, 2023 modern pogroms in Israel and the ensuing conflict in Gaza, antisemitism has morphed into a more subversive intolerance that is, at times, unconscious to the perpetrator. I write to discuss this shift in hope that someone well-meaning, yet unknowingly engaging in this unconscious bias against Jews, is reading.

As the historical evolution of unconscious bias has transformed, a specific framework around defining such transgressions has emerged in the form of microaggressions. A microaggression is a remark or behavior that, even when done inadvertently, offends someone from a marginalized group. This concept is now widely recognized as a prevalent type of unconscious bias in social settings. I’m not necessarily voicing my support for this method of labeling unconscious bias, as there is likely something to be said about assuming best intent, as many social psychologists have asserted. Regardless, this method of calling out bigotry has become the modern standard of addressing discrimination and should thus be applied to all protected groups equally. These norms have recently been cast aside when discussing topics Jews consider antisemitic. It’s one thing to criticize the concept of microaggressions widely, but unless we completely overhaul the systems currently in place to determine discrimination, a double standard will exist against Jews.

Emory University’s Graduate Student Government Association recently proposed a bill to boycott and divest from both Israeli companies and companies with ties to Israel. Some students claim that the bill puts pressure on the Israeli government, a reasonable-sounding goal. However, the impact of the bill, self-proclaimed by the co-author in an Emory Wheel article to be a version of the Boycott, Divestment and Sanctions (BDS) movement, is widely rejected by Jews and deemed antisemitic by the Anti-Defamation League. Unfortunately, this act of unconscious antisemitism was not the only one that has occurred at Emory.

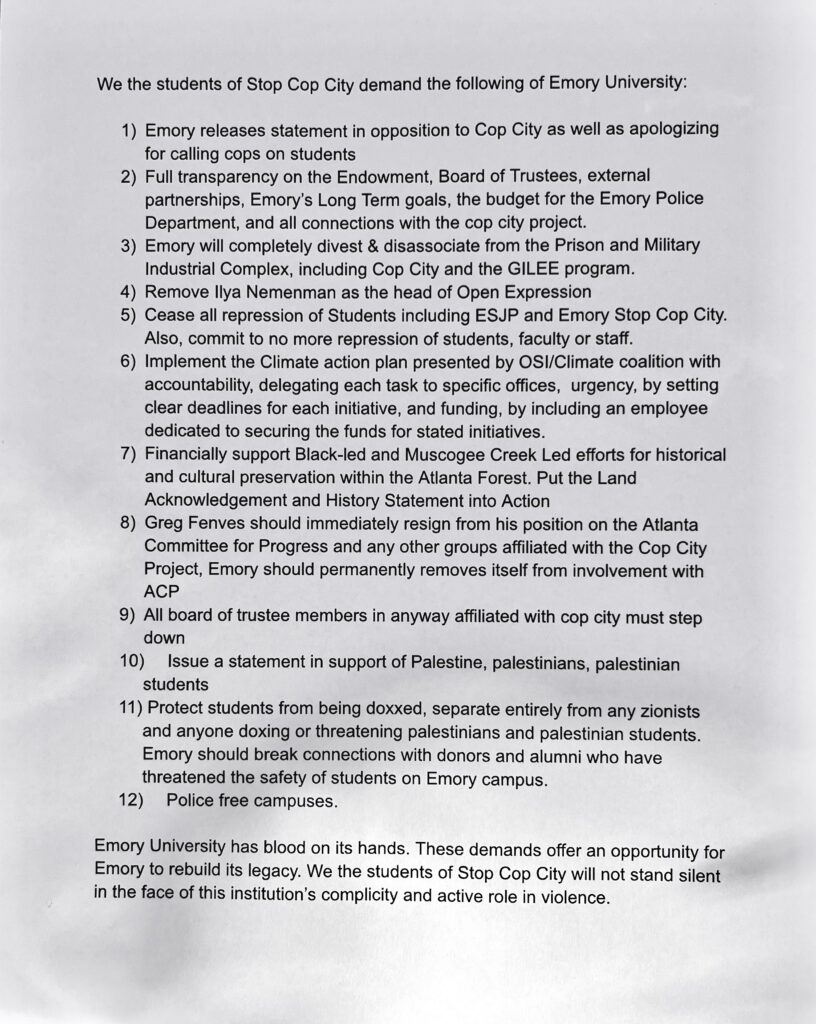

Emory Univerity’s Stop Cop City list of demands from the University. Ben Brodsky/ Staff Writer

In an October 2023 protest, Emory Stop Cop City demanded that the University “separate entirely from any Zionists.” According to the same Pew survey mentioned above, 67% of religious Jews are emotionally attached to Israel, including a whopping average of 80% of Conservative and Orthodox Jews. Emory Stop Cop City’s goal might not be to “separate entirely” from a vast majority of religious Jews, but if Emory accepted its demand, this expulsion would likely be the result. If someone wants to separate from Zionists, and most Jews are Zionists, they therefore want to separate from most Jews. Even if the activist group was well-intentioned, a microaggression against any other minority group would not be accepted and perpetrated by a supposedly progressive social justice movement. By focusing criticism on Zionists, those who critique Israel might unintentionally imply a logic that equates most Jews with Zionists, leading to a disdain for Zionists and, by extension, Jews themselves.

Jews have the right to define what is antisemitic, as other minority groups do for their respective forms of discrimination. After the October 2023 protest, University President Gregory Fenves sparked controversy after critiquing phrases chanted during the rally as being “antisemitic.” In an open letter to Fenves following his response to the protest, Emory faculty members devoted a significant portion of their message to delineating antisemitism according to the Jerusalem Declaration on Antisemitism, which separates any amount of anti-Zionism from prejudice against Jews. A Wheel opinion piece said it best: “Dear non-Jews, don’t tell us what isn’t antisemitism.” The open letter’s signatories’ disagreement with Fenves’ email condemning the chants was written in the name of free expression. The faculty members’ claim is the same as those of former University of Pennsylvania President Elizabeth Magill and former Harvard University (Mass.) President Claudine Gay, defending calls for violence against Jews under the guise of prioritizing free speech. I would be remiss not to note that the University of Pennsylvania and Harvard rank second to worst and worst in the Foundation for Individual Rights and Expression’s 2024 Free Speech Ranking, respectively.

Universities seem to have begun prioritizing freedom of expression post-Oct. 7, 2023. The professors may have a legitimate claim defending the legal free speech of pro-Palestine students. The issue is that this claim is only made when those decrying the arguably hateful speech are Jewish. After Fenves correctly voiced his opposition to the U.S. Supreme Court’s decision to overturn Roe v. Wade in 2022, there was no open letter charging him with silencing those who disagreed with the message. Based on this skewed reception, I argue that progressives only support free speech when those opposing the speech are Jewish. Even if the authors exclusively harbored the intention of defending open expression, the bias is damning.

None of these social justice groups would outwardly admit that their actions attempt to push Jewish students out of progressive movements, classroom discussions on oppression or Emory as a whole. However, this expulsion of Jewish community members may be the unfortunate result of their actions. This year, Harvard and other elite universities saw their applications fall significantly. This decrease is inseparable from the discomfort and fear that Jewish applicants have felt following the actions of their community members. You might not be trying to expel Jews from your spaces, but the refusal to acknowledge and correct this reality is, by definition, antisemitic. I’m not focusing on my own opinions on Zionism, the BDS movement or campus free expression. I mainly question why those who are quick to call out other forms of discrimination are hesitant to condemn antisemitism. If the current climate, both at Emory and around the country, continues, consciously or unconsciously, Jewish community members may choose to go somewhere else. If well-meaning anti-Zionists wish to keep Jews in their academic, social and political spaces, they should grasp the consequences of their words and reverse course.

Ben Brodsky (25B) is from Scottsdale, Ariz.

Ben Brodsky (he/him) (25B) is from Scottsdale, Arizona. He has explored hip-hop history since 2019, first on his blog SHEESH hip hop, and now with “Hip Hop Heroes,” a series of essays on narrative in hip-hop. When not writing about Jay-Z, you can find him writing “Brodsky in Between,” an Opinion column on political nuance, graphic designing and playing basketball.