Georgia’s controversial heartbeat bill went into effect July 21, banning abortions once a doctor can detect “embryonic or fetal cardiac activity” in the womb six weeks into the pregnancy.

Gov. Brian Kemp signed the bill, also known as the Living Infants Fairness and Equality (LIFE) Act, into law in 2019, but the law had been struck down in 2020 by the federal court, ruling that the measure was unconstitutional under precedent set by Roe v. Wade.

In the wake of the U.S. Supreme Court’s June 24 decision in Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization to overturn Roe v. Wade — which protected the right to abortion — the bill was given a second chance in the courts.

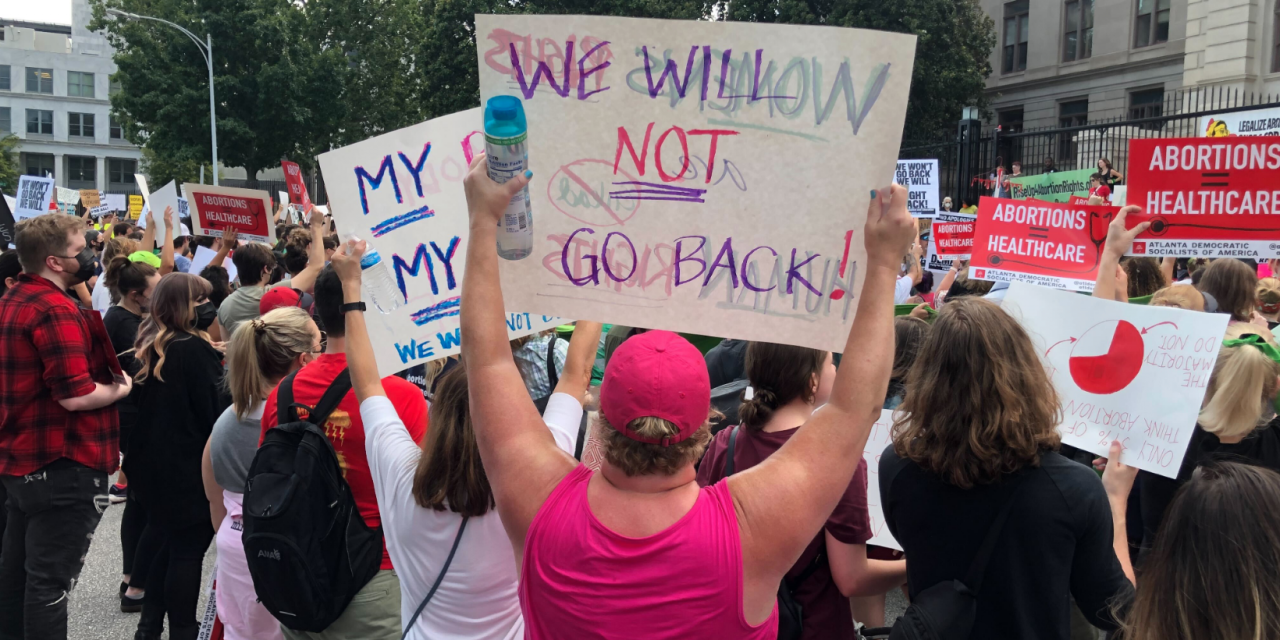

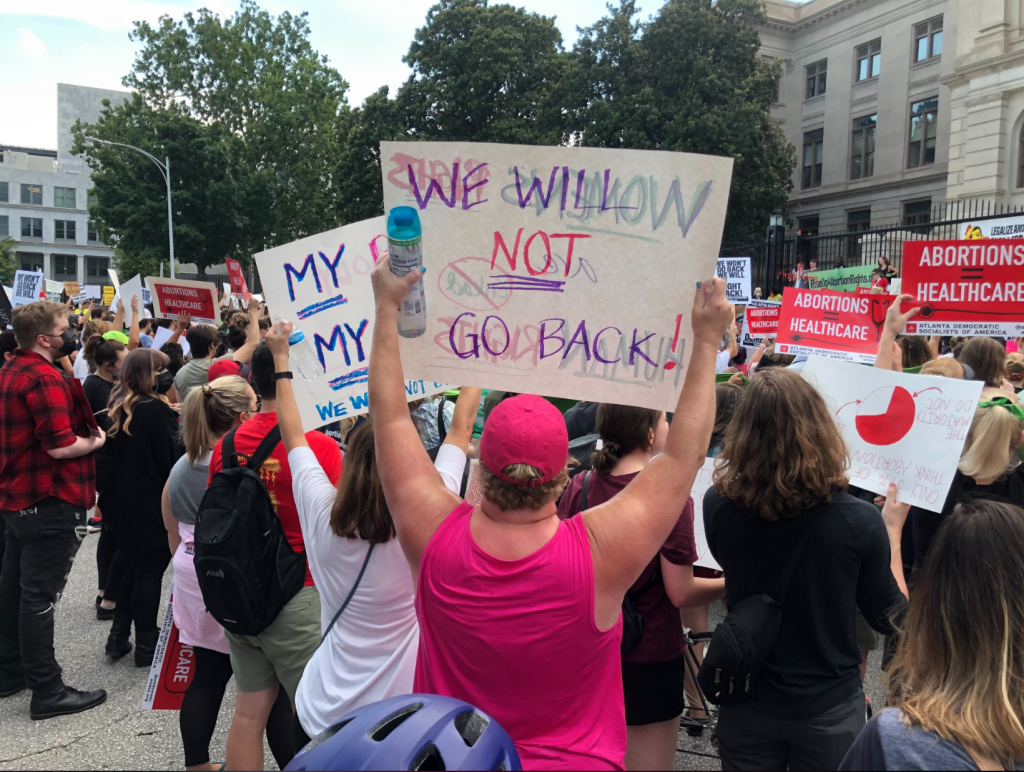

A crowd of people covered the street in front of the Georgia State Capitol Building on June 24, protesting the Supreme Court’s decision to overturn Roe. Photo courtesy of Chloe Yang (22C).

Arguing that the state now has a “rational basis” to enforce the LIFE Act, the 11th Circuit Court of Appeals, a federal court in Atlanta, overturned the lower court ruling that blocked the heartbeat bill on July 20. The Dobbs v. Jackson decision “makes clear no right to abortion exists under the Constitution, so Georgia may prohibit them,” the court stated.

The six-week abortion ban permits abortions past six weeks if the pregnant person’s life is at risk or if a medical condition makes the fetus unviable. The law also includes exceptions for abortions 20 weeks into the pregnancy or less if the pregnancy was a result of rape and incest, and if the pregnant person reported the incident to the police.

However, most sexual assault cases go unreported, with just 31% of sexual assault survivors reporting their case to the authorites, the Rape, Abuse and Incest National Network finds. Common justifications for not reporting sexual assault incidents include fear of retaliation, belief that the police won’t help or belief that the case is a personal matter.

Kemp wrote in a July 20 statement that he was “overjoyed” by the Court’s decision.

“Since taking office in 2019, our family has committed to serving Georgia in a way that cherishes and values each and every human being, and today’s decision by the 11th Circuit affirms our promise to protect life at all stages,” Kemp wrote.

Sara Redd, a postdoctoral fellow at Emory University’s Center for Reproductive Health Research in the Southeast (RISE), said the heartbeat bill will “completely decimate access here in Georgia.”

A Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) study found that over 50% of reported abortions in Georgia in 2019 were performed after six weeks of gestation.

Using data gathered by the Georgia Department of Public Health between 2007 and 2018, Redd and her RISE coworkers predicted that if a six week ban is implemented, 65-70% of abortions currently being performed in Georgia will become illegal.

“That is, of course, a huge decrease in the number of abortions that are provided here in the state,” Redd said. “It’s just going to be devastating for people, not only for Georgians, but also people in our surrounding states who are coming here to get care.”

Redd noted that Georgia’s former 22-week abortion ban has allowed the state to be a “hub for abortion access in the south,” as neighboring states have stricter laws. This includes Alabama, which has banned abortion at any stage of a pregnancy unless the mother’s life is in danger since 2019.

In 2019, Georgia ranked fifth for the number of abortions provided per state.

Realistically, the six-week ban will leave individuals with only two weeks to schedule an abortion because most people do not find out they are pregnant until at least four weeks after gestation. This means someone’s period would only be about two weeks late by the time abortion is no longer an option, Assistant Professor at the Rollins School of Public Health Elizabeth Mosley, who also works for RISE, said.

“Anyone who maybe has an irregular period, has other health complications going on, is just busy, they’re not going to realize that they are pregnant,” Mosley said. “So a six-week limit is essentially an all-out ban on abortion.”

The approval of the heartbeat bill gave way to an expansive personhood provision in Georgia. The state’s department of revenue announced on Aug. 1 that fetuses now have “full legal recognition” as living people, meaning that if a fetus has a “detectable human heartbeat,” their parents can count them as dependents on taxes in the amount of $3,000 each.

In addition to tax breaks, Georgia’s personhood provision requires that fetuses are included in some population counts, and requires fathers to pay child support for their unborn babies.

The end of Roe v. Wade

When asked for her opinion on the U.S. Supreme Court’s June 24 decision to overturn Roe v. Wade, Redd let out a deep sigh.

“It’s almost hard to put into words how devastating this decision is, and how devastating it is going to be,” Redd said.

But for others, the landmark decision was a cause for celebration. In a June 13 interview, Martha Zoller, the executive director of the pro-life organization Georgia Life Alliance, said she hoped Roe v. Wade would be overturned.

“That means that God will be upheld,” Zoller said. “People are talking about Roe v. Wade a lot, but it’s really God being upheld, and if [He’s] upheld, then that will make Roe v. Wade moot.”

The 6-3 ruling in Dobbs v. Jackson marked the end of nearly 50 years of federally protected abortion access under Roe v. Wade, coming almost two months after Politico obtained a leaked draft majority opinion indicating that the Supreme Court planned to overturn Roe v. Wade.

Some politicians have spoken out against the Supreme Court’s decision, including U.S. President Joe Biden, who signed an executive order on July 8 to secure access to abortion medication and emergency contraception. The order also aims to establish an interagency task force to employ “every federal tool available to protect access to reproductive health care” and protect patient privacy, following concerns that those seeking abortions could be prosecuted based on personal information in emails, texts and internet searches.

However, Biden does not hold the power to reverse the Supreme Court’s ruling and reinstate the nationwide right to abortion. To do so, Congress would have to restore the protections previously provided under Roe v. Wade as federal law.

This gives individual states the power to ban abortions, leaving Americans waiting to see what the United States will look like in the wake of Roe’s downfall.

“What this decision has done is it has taken away the protections at the national level, and it has made it such that it’s a states’ rights issue or a state level decision,” Associate Professor of Global Health and RISE Affiliated Faculty Dabney Evans said. “What that really means is that we now will have a patchwork of different options for people depending on where they live.”

Impact of the ruling on Emory University

Emory Healthcare — which is made up of 11 hospitals, the Emory Clinic and over 250 provider locations — will continue to provide abortions services, although limited under the recently-approved heartbeat bill.

“Emory Healthcare remains steadfast in its commitment to providing excellent and equitable healthcare to patients and supporting providers as they perform these services,” Assistant Vice President of Communications Laura Diamond wrote in an email to the Wheel. “As part of this work, Emory Healthcare will perform abortions in compliance with state and federal law.”

The Dobbs v. Jackson ruling and subsequent Georgia legislation limiting abortion access may hinder Emory-provided abortion services and coverage, including through the Emory University Student Health Insurance Plan (EUSHIP). Emory requires all degree-seeking students to be enrolled in a health insurance plan, so students who don’t have a different health insurance plan or who don’t request a EUSHIP waiver are enrolled in the student plan.

University President Greg Fenves acknowledged these likely limitations in a June 24 email to the Emory community — the same day as the Supreme Court ruling, which he called a “painful regression.”

“As a university and as an employer, Emory is highly likely to face new limits on the reproductive health care coverage we can offer our students, faculty and staff,” Fenves wrote.

Fenves added that the University is “working closely with partner organizations throughout the state to review and adapt to these changes.”

However, as of August 8, EUSHIP coverage of “voluntary sterilization for males” and “voluntary termination of pregnancy” for the 2022-2023 academic year remains unchanged from the previous year. Under this category, “covered medical expenses include charges for certain family planning services, even though not provided to treat a sickness or injury.”

The plan covers 90% of the negotiated charge for procedures in Emory’s “core network,” 80% of the negotiated charge for “preferred care” and 60% of the recognized charge for “non-preferred care.” Insurance benefits are limited to $500 per policy year for voluntary pregnancy termination. The plan does not make such a stipulation about male sterilization procedures.

“Under current deductible and co-insurance structures for all medical services for EUSHIP patients during academic year 2022-23, out-of-state preferred providers are covered at 80 percent and out-of-state non-preferred providers at 60 percent,” Diamond wrote in an email to the Wheel. “Students should contact EUSHIP directly to learn what support resources are available when a medical procedure is not available locally.”

An abortion during the first trimester (weeks 1-12) can cost up to $750, although it is often less. Second trimester (weeks 13-24) abortions can reach $1,500. Vasectomies — which are about six times cheaper than female sterilization — can cost up to $1,000.

In response to whether the Emory student insurance plan will still cover $500 toward abortion services, Diamond wrote, “The Emory University Student Health Insurance Plan provides comprehensive family planning services — including reproductive care — for our students.”

Student Health Services will continue to provide emergency contraception during the 2022-23 academic year.

Young Democrats of Emory Vice President Divya Kishore (23C) said that she hopes Emory uses its funding to help students access abortion care.

“I don’t know how much Emory can do in terms of changing student insurance, but I do know that Emory could have the ability to create some type of mutual aid fund for students who are seeking that care and can’t afford it,” Kishore said. “Emory could work with them, if it’s a tuition break or something, in order for them to receive life-saving medical care.”

When asked about how the Dobbs ruling may impact students, Emory College Republicans Chairman Robert Schmad (23C) wrote that maybe they will take his advice and “stop having sex outside the confines of (an ideally Christian) marriage!”

Describing his reaction to Politico’s leaked draft opinion, Schmad wrote that it was like “clutching a Fortnite victory royale for the conservative movement.”

“Almost all my pro-life friends were equal parts ecstatic and astounded,” Schmad said. “The right, and the religious right in particular, isn’t accustomed to winning culture war battles.”

Based on Catholic Church teachings detailing abortion as a “grave sin,” Schmad added that abortion should be illegal in all cases where the mother’s life is not endangered. He wants Republicans’ next step to be advocating for a federal ban on abortion alongside expanding social programs for new mothers.

“Non-white and working class Americans are increasingly turning their backs on the Democratic Party’s progressive agenda and, frankly, the nation’s political institutions structurally favor Republicans,” Schmad wrote. “We’re on the cusp of a conservative decade and the ending of abortion is just the start of what we’re going to do.”

Young Democrats of Emory President Ash Shankar (23B) described Roe’s end as a “step backwards in history.”

“Not only are we going to somewhere where women and people with uteruses don’t have access to healthcare, but we’re going to a place where we’re going to make it so much harder that people are going to have to turn to methods that might not be as safe and endanger so many lives,” Shankar said. “We’re putting so many people at risk for the political appeasement of the courts.”

Although Shankar called Fenves’ June 24 email a “right step,” he said he wants to see Emory take “tangible action” in response to the decision to overturn Roe, specifically by using the University’s influence to push back against legislation that aims to reduce abortion access.

“We really want to see Emory take a frontline stance against this heartbeat bill, because it doesn’t make any sense to restrict people’s right to choose, especially at six weeks when most people … don’t know if they’re actually pregnant,” Shankar said. “It’s absolutely ridiculous.”

However, Schmad views Fenves’ June 24 email as taking too much of a stance, potentially harming open discourse on campus.

“Even though Fenves paid lip service to free expression in the email he sent out, his actively taking a pro-choice stance will have a chilling effect on campus discourse,” Schmad wrote. “When students perceive that their institution is hostile towards a given set of beliefs, it’s only rational for them to be hesitant to publicly tout them given the costs associated with doing so.”

Emory community members have already responded to College Republicans’ position on Dobbs v. Jackson — which the group shared in a June 28 Instagram post — with “insults, threats and bad faith portrayals of our beliefs,” Schmad wrote.

The group’s Instagram post was flooded with over 900 comments. Commenters largely denounced the College Republicans’ stance, stating “Don’t call yourselves republicans you’re religious extremists who support the death and oppression of anyone who isn’t a ‘Christian’ conservative white cis het male. History is not on your side,” and “There is so much wrong to unpack here I could teach a seminar. It’s every type of ignorant packed into one post.”

Schmad added that abortion is a difficult topic for genuine discourse to be productive.

“Attempting to use reason alone to resolve moral questions results in discussions that are interminable,” Schmad wrote.

Emory has taken a stance on political matters in the past. On June 5, 2020, former University President Claire Sterk and Fenves, who was president-elect at the time, wrote a letter to Kemp, urging him to pass legislation against hate crimes and offering Emory’s assistance in the process. Kemp later signed a hate crimes bill into law on June 26, 2020.

“President Fenves seems to have a very strong, or at least somewhat visible, relationship with Governor Kemp, and Emory plays such a large role in the community,” Shankar said. “I can 100% see Emory’s administration lobbying the legislature of Georgia, lobbying the governor, telling them that this is not something that Emory as a large institution in the state wants, or all of the stakeholders that are involved in this institution.”

Kishore agreed with Shankar, saying that Emory should “take advantage” of its role as a major healthcare provider in Georgia.

“Emory also employs so many individuals — we have so many students, so many faculty, so many staff — and that’s a very large number of people we’re talking about who are going to lose reproductive care,” Shankar said. “It’s really the responsibility of Emory administration to advocate for these people that they’re employing and ensure that the people who are trusting them as an employer are able to receive the care that they 100% need.”

Impact of the ruling on Georgia

A slew of “negative consequences” can follow for those who are turned away for abortions in Georgia under the heartbeat bill, Mosley said.

“That includes things like being trapped in abusive relationships, being more likely to live and be stuck in poverty, and negative mental health effects including depression, anxiety and substance use,” Mosley said.

Evans said that the United States is not reverting back to a pre-Roe period, where people resorted to methods such as coat hanger abortions. Mosley noted that there are several resources available for people seeking abortion care in Georgia. She recommended the Feminist Women’s Health Center, which is an Atlanta-based clinic offering medication and surgical abortion care, and Access to Reproductive Care (ARC) Southeast, which is an abortion fund covering Georgia among other states.

AIDAccess and Women on Web provide resources for people who wish to self-manage abortions at home with medication, Mosley added. She said that medications — which are available online — can safely induce abortion for up to 12 weeks of pregnancy, although the use of medications is limited after six weeks due to the heartbeat bill.

“Even though it feels like we don’t have control over our bodies anymore, we still do,” Mosley said. “There are resources and educational materials that can help us still control our bodies and our lives.”

However, unsafe abortions will still likely increase among women who have a harder time accessing these resources, Evans noted.

“Unfortunately, there will be people that will not have the resources to be able to access abortion, and those people are going to be in difficult situations and we don’t know the kinds of measures that they might take,” Evans said.

The abortion ban will disproportionately affect the Black community, which historically seeks abortions at higher rates than white people, Mosley said. She explained that this is due to a variety of factors, including the inability to access contraceptives or afford to raise a child because of “racialized poverty.”

This trend is striking in Georgia. According to a CDC study, Black individuals received 64.9% of reported abortions in Georgia in 2019, while white people received 21.2% of reported abortions.

Out of all industrialized countries, the United States has the highest number of pregnancy-related deaths. Georgia ranked second out of the 50 states for maternal mortality rate, which is disproportionately higher for Black patients.

Mosley explained that the Black maternal mortality rate will likely increase following Roe’s end.

“A major driver is racism in our health care system, where providers don’t listen to Black pregnant people who are experiencing complications,” Mosley said. “We also know that because of chronic racialized stress, Black people are more likely to come into pregnancy with pre-existing conditions that then put them at higher risk of complications and mortality.”

The LGBTQ community also faces healthcare discrimination. Redd explained that, in addition to cisgender women, many nonbinary people and transgender men can also get pregnant. However, nonbinary and transgender patients often have a harder time finding compassionate and gender-affirming healthcare providers than their cisgender counterparts,

“All of those things sort of compound on one another and make it more difficult for people to actually get care that is safe for them, and actually affirming for them,” Redd said.

Abortion restrictions will also disproportionately affect lower income individuals, ultimately worsening the impact on Black and LGBTQ communities, Rollins Assistant Professor and RISE Director Whitney Rice explained.

According to the 2020 U.S. Census, 19.5% of Black people lived in poverty, while only 8.2% of non-Hispanic White people reported the same. Similarly, a 2019 study by the Williams Institute found that LGBTQ people have a poverty rate of 21.6%, while cisgender heterosexual people have a poverty rate of 15.7%. Transgender people and cisgender bisexual women have the highest poverty rates of 29%.

The ruling also has the potential to exacerbate class differences, Redd said. If someone wants an abortion but lives in a state with heavy restrictions, they will likely need to travel to a state with more open policies to receive the procedure, which can be expensive.

Georgia is largely bordered by states with strict abortion bans — the procedure is banned after six weeks in South Carolina and Tennessee, while abortion is completely banned in Alabama. As a result, Georgians who want to get an abortion after six weeks will likely have to travel to either North Carolina, where abortion is available until fetal viability around 24 to 26 weeks of pregnancy, or Florida, where abortion is legal up to 15 weeks.

Even if people travel to abortion clinics, they will likely be met with long wait times. The New York Times reported that before Roe was overturned, abortion clinics in most of the country had an average wait time of five days. However, abortion clinics near states with bans have seen an increase in wait times since Roe was overturned — 22% of such clinics are now booking appointments three weeks out.

People may need to take off work to travel for abortions, but oftentimes lower-income people work jobs where doing so is a greater challenge, Redd said.

Some large corporations, including Amazon, Starbucks and CNN, announced that they would be covering employees’ travel costs for abortions in their insurance packages. Wes Longhofer, the executive academic advisor of Goizueta Business School’s Business and Society Institute, said that although the companies’ action is good because it reduces political tension and normalizes conversations on abortion, it will not directly benefit the majority of the population.

“It’s just the reality that most women who would be affected by these restrictive policies do not work for these companies,” Longhofer said. “Half of employment in the U.S. is in small businesses, many of which may not be able to afford these benefits, even if they wanted to provide them.”

However, Longhofer added that more companies will likely begin to cover abortion travel as a strategy to recruit and retain employees.

“It remains to be seen what happens in states like ours, though,” Longhofer said. “There’s concern that legislatures may go after companies that are paying for out-of-state abortions under their restrictive policies.”

Besides travel, many people below the poverty line also struggle to pay for the procedure itself. Under the Hyde Amendment, federal funds cannot be used to cover abortions for people enrolled in Medicaid, Medicare and the Children’s Health Insurance Program, unless the pregnant person’s life is in danger, or in cases of incest or rape. This leaves the decision regarding abortion coverage to the states.

Georgia Medicaid only covers abortions in cases of life endangerment, rape and incest, which often forces people to pay out of pocket for abortion services, Assistant Professor and RISE Affiliate Faculty Subasri Narasimhan said.

“We’re probably going to see an exacerbation of these kinds of financial barriers making clinic-based abortion out of reach for certain people,” Narasimhan added.

The ruling may worsen an ongoing OB-GYN shortage in Georgia, particularly in rural or impoverished areas, Redd said. Atlanta Magazine reported that half of Georgia’s 159 counties do not have a single obstetric provider.

Evans explained that normalizing these conversations about abortion — ranging from private discussions between family members to celebrities and corporations publicly voicing their opinions — “is going to be really important as we move forward in this country.”

“The reality is that every single person on this planet knows someone and loves someone that has had an abortion,” Evans said. “Abortion is not a dirty word and we shouldn’t be afraid to talk about it.”

Update (8/8/2022 at 7:40 p.m.): This article was updated to include an updated statement by Assistant Vice President of Communications Laura Diamond