Creative Commons/Flickr

If you have even opened your social media accounts in the past year, then I am sure you are no stranger to the name Colleen Hoover. A budding BookTok sensation, this middle-aged social worker turned author from Texas has swarmed the popular scene, dominating fiction sales. For more than a year, 42-year-old Hoover has had three to six books on Publishers Weekly’s top 10 bestseller list on any given week.

Her success is typically attributed to her loyal online fan base — largely teenage and young white women — who fervently refer to themselves as her “CoHorts.” Their TikTok videos donning these pastel-clad chronicle covers seem to go viral instantaneously, driving titles such as “It Ends with Us” and “Verity” further and further up the charts. However, it is unclear what exactly is causing these novels to gain so much traction, and Hoover’s claim to fame has not come without controversy. She has recently come under fire in the literary community for both personal and literature-related incidents that have caused readers such as myself to shy away from her bestsellers.

Hoover is often critiqued for the way she writes about romance, and many fear that her overly-graphic scenes regarding relationship dynamics and sexual interactions do not set an empowering example for her young female audience. Emory students who have read “It Ends with Us” share this sentiment.

Anika Banerjee (26C) stated that she was “concerned” upon discussing the novel with friends, as many wanted the extremely abusive relationship depicted “to work out in the end.” Banerjee did not place blame on these readers, but instead on Hoover for how she “perpetuates misogynistic themes and capitalizes off of them.”

Thalia Papageorgiou (26C) found her novels to be similar to “fanfic,” stating that “the plot tried to simplify trauma.”

“I didn’t like how at the conclusion of the novel, it was the actions of another man that convinced her to leave her toxic relationship, not by her own accord,” Papageorgiou wrote in a message to the Wheel.

Accusations in Hoover’s personal life have not helped to reverse this narrative. Her 21-year-old son, Levi Hoover, was recently accused of sexually harassing a young woman via text message when she was 16. According to the woman, the younger Hoover was aware of her age. Hoover addressed these accusations in a private Facebook group dedicated to herself, stating that she holds her son accountable for sending an inappropriate message.

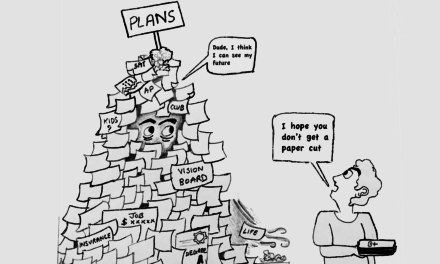

In light of Hoover’s involvements, many readers, including myself, have chosen to not consume Hoover’s literature. I believe that Hoover is allowed to write about issues such as domestic violence and rape in the name of artistic expression, but the issue lies in the way she chooses to market herself. By labeling herself as a romantic novelist, littering the covers of her books with flowers and feathers and bows, Hoover is glamorizing these events — whether she intends to or not.

Readers can use their own moral compasses in the matter of separating the art from the artist. If you are not comfortable with possibly condoning the themes of Hoover’s novels or personal accusations but are still interested in her work, you can purchase it from a secondhand source such as eBay or a thrift shop.

However, a separate crowd is encouraging readers to shy away from Colleen Hoover for an alternate reason: they believe her writing is simply not up to par for all of the attention that it is getting. Her diction is tired, they argue, and she uses the absurdity of her plots to shade her unremarkable descriptions and metaphors.

While I support uncensored literary criticism, I feel that a large portion of the hate that is directed toward Hoover’s writing reeks of elitism, and that it often seeks to demean those consuming the literature rather than condemn Hoover herself. If we continually insult non-readers for picking up a “subpar” book, why would we expect them to go read anything else?

Many of Hoover’s “CoHorts” have stated that her books have allowed them to get back into reading for pleasure, something they have not enjoyed since their youth. With so many competing factors for people’s attention in the modern day, those of us who appreciate books should be happy that others are reading, regardless of the circumstances. We have cutting-edge television series like “This Is Us” that encourage us to ponder and re-evaluate the world around us, and then we have “Toddlers and Tiaras.” Media does not need to be brilliant to serve its purpose of entertaining. In the world of capitalism, it can be more financially rewarding to choose the simplistic rather than the revolutionary. Condemning Hoover for profiting off of her plot-heavy novels rings oddly familiar to those who degrade the Kardashians for how they became wealthy. Like it or not, they worked the economic machine that we live in efficiently. It doesn’t need to be fair, it’s laissez-faire.

A large majority of the critiques of Hoover’s books are coming from academic or prestigious publications, which argue that Hoover’s writing style lacks literary complexity. However, these complex elements are learned through higher education, something that many individuals in America simply don’t have access to — including Hoover herself, who grew up in an abusive, lower-middle-class household.

Hoover wrote her first novel, “Slammed,” on a borrowed laptop when she was working as a social worker and living in a trailer home with her family. She intended for it to be a Christmas present for her mother but decided to research how to self-publish a novel. Without going through the editing rigor of a traditional publishing house, “Slammed” hit the market and began to climb the charts through word of mouth and early social media platforms such as Tumblr and MySpace.

Hoover may not be the most meticulous writer. She may stray away from the techniques and additives that we — as the inherently privileged population that attends Emory University — have been taught to identify as academically acceptable. When we classify writing as good or bad without acknowledging that we associate good with the most intellectual, we fail to recognize how we are forming a sort of literary caste system.

Sure, Hoover may lack what academia desires. But she has brought herself and her family out of a financially troubling situation and entertained millions of young readers with her material. Sure, I believe that there is better literature out there, literature that explores heavy topics through a more ethical lens and does maltreated individuals far more justice. But if you tell these young readers who have just begun to dip their toes into the pool of reading for pleasure that what they like is bad, how do you expect them to continue exploring the world of books?

It’s like ripping out a flower before it has started to bud. Who are we to squash the interests of others when we participate in a field often stated as dying, as AI bots and content creators waive daggers over our heads. I’m not telling you to run to your nearest Barnes and Noble to pick up Hoover’s next release. However, you need to check your elitism and evaluate why you really want to tell someone else not to do so.

Maddy Prucha (26C) is from Long Island, New York.

Madeleine Prucha (she/her) (26C) is from Long Island, New York, majoring in economics and human health and minoring in English. She previously served as president of her high school's paper, The Gull, for which she founded a creative writing column. She is highly involved in NEDA Campus Warriors, Emory Gymnastics and Kappa Alpha Pi. In her free time, you can find her baking for her Instagram account, listening to the La La Land soundtrack or threatening to beat people in a badminton match.