The Emory University Hope Clinic hosted the DeKalb Department of Public Health (DPH) to provide free monkeypox vaccinations to those eligible to receive the vaccine on Aug. 25.

Eligibility requirements included being at least 18 years old and being a man who has sex with other men (MSM), or people who regularly have close, intimate or sexual contact with persons who are MSM, among others.

A total of 36 vaccine doses were administered during the clinic event, Eric Nickens, the Manager for the DeKalb County Board of Health Office of Communications and Media Relations, said.

The Emory Hope Clinic is also starting a monkeypox vaccine study next week, Paulina Rebolledo, an MD investigator at the Hope Clinic, said. Healthy adults who are interested in participating in the study should contact the clinic about volunteering.

Though the Emory Hope Clinic — which is part of the Division of Infectious Disease at Emory School of Medicine — provided space and assisted with vaccination, Executive Director of Student Health Services Sharon Rabinovitz said that there are no plans for Student Health Services to provide the vaccine themselves.

The monkeypox outbreak has infected 18,416 people in the United States and 49,974 people worldwide. On Aug. 30, the first death in a severely immunocompromised person with monkeypox in the U.S. was confirmed in Texas.

Georgia has the fifth highest number of reported monkeypox cases of any state in the United States with 1,387 cases as of Aug 30, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC).

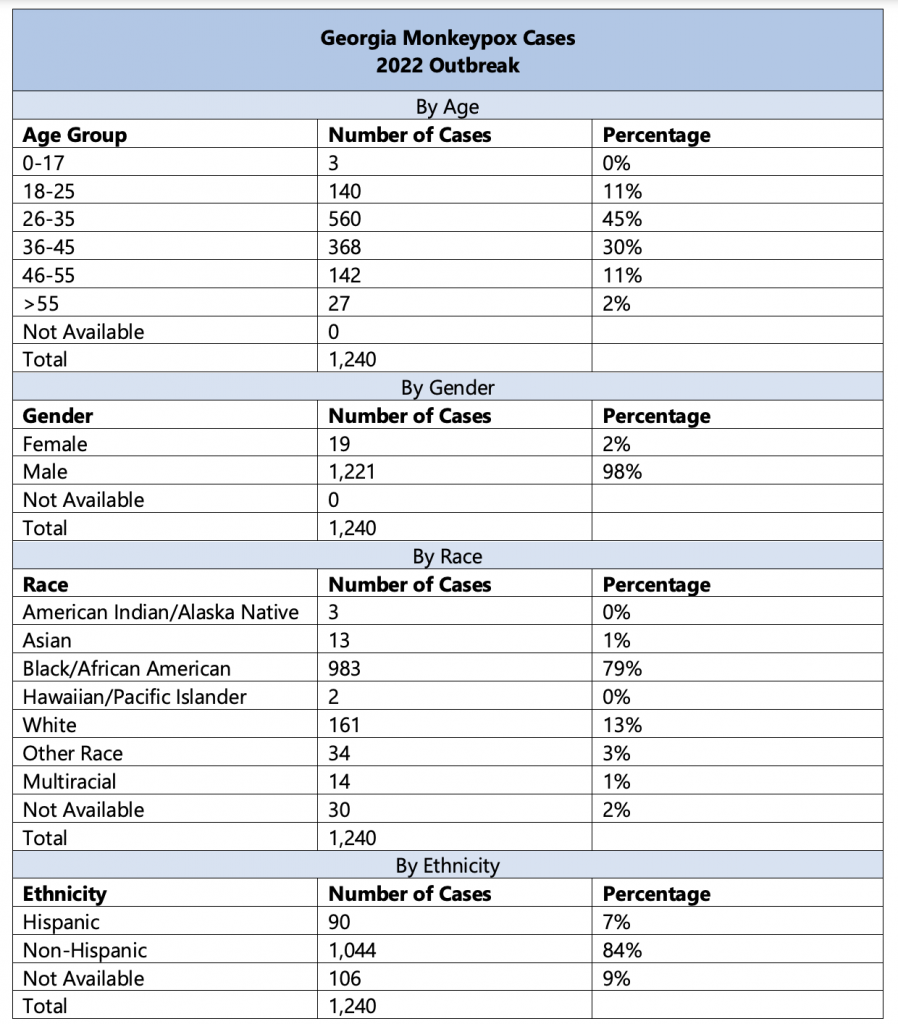

Monkeypox cases in Georgia as of Aug. 24. Table courtesy of Georgia Department of Public Health

Experts in the field have “a lot of concern” over the spread of monkeypox in college, Carlos del Rio, executive associate dean at the Emory University School of Medicine, said.

“If it gets into colleges, there’s going to be a lot of transmission,” del Rio said.

Director of the Emory Global Health Institute and former Director of the Center for Global Health at the CDC Rebecca Martin agreed, noting that there should be strong surveillance in areas with close living spaces, such as colleges.

Monkeypox has been on the University’s radar for several months, Rabinovitz said, and the University has been establishing plans and protocols to manage the virus since then.

“Monkeypox is very different from COVID, but from a public health standpoint, we do similar things,” Rabinovitz said. “We want cases to be identified, tested and then resources allocated to them to support them.”

Rabinovitz also said that a house on Eagle Row will be used as an isolation space.

Martin said that students should be aware of their risk and act accordingly.

“Individuals at school and students should think about, ‘What is my risk personally? What can I do to help prevent it or reduce my risk?’ And make sure you have all the facts and get vaccinated,” Martin said.

Students who develop monkeypox symptoms such as a rash or have been exposed to someone with a known monkeypox rash should make an urgent care appointment at the Student Health Center, according to the Student Health website.

Jeannette Guarner, a Professor of Pathology and Laboratory Medicine at Emory University Hospital, added that if a student is in a high-risk group, they should consider reducing their number of sexual partners. High-risk individuals currently include gay, bisexual and other men who have sex with men, according to the CDC.

The CDC also suggests that individuals keep themselves safe from monkeypox during sex by having virtual sex or wearing gloves when performing sexual acts online.

‘This, in many ways, feels like the early days of HIV’

John Stanton (98PH, 17N, 18N, 22N) remembers what it was like to be LGBTQ+ during the dawn of the AIDS epidemic, which devestated the LGBTQ+ community – particularly gay men – throughout the 80s and 90s. By 1995, one gay man in nine had been diagnosed with AIDS, and one in fifteen had died from it.

“[It’s] something that’s important to me, that I’ve lost friends to,” Stanton said.

Stanton said that’s why he now manages the Decatur arm of the Positive Impact Health Centers, an infectious disease organization that serves Georgians living with or at risk for HIV.

Stanton has seen the amount of patients coming in with monkeypox symptoms “exponentially grow” over the past few months. In just eight weeks, Stanton went from treating just one patient to having 25 under his care.

All of his patients have a lesion, and its appearance has varied from “a pimple” to a “more disseminated, pox-like rash,” Stanton explained. Other signs of monkeypox include a “fever, body-ache, and cold and flu-like symptoms,” he added.

Monkeypox has been spreading almost exclusively through skin-to-skin contact during sex among gay and bisexual men. About 94% of patients who provided demographic information to clinics reported male-to-male sexual or close intimate contact during the three weeks before symptom onset, according to the CDC.

Stanton cited smaller sexual networks as a cause for the spread in the LGBTQ+ community.

“Our social networks are a much smaller percentage of the population, and they’re thereby tighter and interconnected,” Stanton said.

While everyone has responded to the outbreak differently, fear and apprehension prevail in the LGBTQ+ community, Stanton said.

“Both as a provider or a member of the community, this, in many ways, feels like the early days of HIV,” Stanton said. “ I feel very much, like HIV, we’re not responding fast enough to something that’s hitting a perceived portion of the community for which, in reality, everybody’s at risk.”

Assistant Professor of Medicine in the Division of Infectious Diseases Boghuma Titanji also emphasized that everyone is at risk and that monkeypox does not spread solely through sexual contact.

“You can also get transmission through prolonged contact with contaminated inanimate objects used by someone who is infectious, or in very rare circumstances, through a droplet or aerosol transmission route,” Titanji said.

Georgia has already seen three cases of monkeypox in children, which “are considered to be household transmission,” DPH spokeswoman Nancy Nydam told the Atlanta Journal-Constitution. Household transmission would include touching contaminated bedding, clothing or other fabrics used by someone with monkeypox.

The racial disparity of monkeypox in Georgia

According to Aug. 24 DPH data, 79% of the state’s cases are among Black people, who make up only 31% of the state’s population.

While the stark racial inequity in Georgia monkeypox infections is “horrifying and enraging” to Justin Smith (19G), Director of the Campaign to End AIDS at Positive Impact Health Centers, he said it is not surprising. Smith explained that the demographics reflect the pattern seen in most types of infectious diseases.

“We know that for most communities in the U.S., diseases follow these kinds of established social fault lines that we have, and so the people that are the most marginalized will always experience the highest level of harm,” Smith said.

However, the reasons for the disparities are manifold, he added.

“There isn’t one reason why we see that pattern,” Smith said. “It’s tied to things like structural racism. It’s tied to inadequate access to health care services.”

Graphic courtesy of Georgia Department of Public Health

Titanji agreed, noting that there is also inequality in vaccine distribution. She cited monkeypox vaccination data from North Carolina, where 70% of those infected with monkeypox are Black gay, bisexual or other men who have sex with men, but 67% of the vaccines have been administered to white individuals.

“Again, showing you that disparity that exists, really driven by the social determinants of health — poverty, racism and just a disproportionate balance in who is able to have access to the tools,” Titanji said.

One element of monkeypox that exacerbates inequities, Smith noted, was the long isolation period. Those with monkeypox typically have to isolate for two to four weeks, which Smith said could be unfeasible for many.

“If you’re working a service job or some type of position where you have to be in person in order to earn your wages, that produces a lot of difficulty,” Smith said. “One of the things that I am hoping is that, now that it’s become declared as a public health emergency, there’ll be funding that could help people supplement their income so if they need to take time off, that there are ways that folks can be supported with the financial resources.”

Black and Hispanic Americans are overrepresented in jobs that require work from outside the home and in jobs that are less likely to provide paid leave, according to a University of Illinois Chicago study.

Stanton echoes this, indicating that financial support for isolation should’ve been taken into account after COVID-19.

“When you think about the community that this is impacting and other disparities that the community goes through, in terms of socioeconomic disadvantage, most people are not in a position where they have a job that they can say, ‘Oh, hey, you know what, I’m not going to be here for four weeks,’” Stanton said. “We haven’t seen a response either from state or federal public health like we saw with COVID, in terms of helping people financially with rental assistance, food insecurity.”

‘We saw this coming’

Titanji, Martin, del Rio and Guarner all said that the response to the monkeypox outbreak has been too slow.

The demand for vaccines is currently greater than the supply, Titanji noted. As of Aug. 24, there were 16,467 monkeypox vaccines administered in Georgia, but a shortage of the vaccine – on both a federal and state level – has persisted.

Additionally, testing for monkeypox is still minimal — there is no home test, and results from a clinic can take days.

Public health authorities “should have been prepared for monkeypox,” del Rio said. He added that public health agencies’ focus on the COVID-19 pandemic over the last two years likely contributed to a lack of preparedness for monkeypox, given how exhausted the agencies are.

Martin said she hoped the response to the outbreak would have been faster.

“I think we saw this coming … during COVID we’ve learned that vaccine supply was a very big issue,” Martin said. “We recognized that we needed stronger systems and manufacturing and regulations and all these components that we have not put into practice yet at the level that they need to be.”

Martin added that the nation has a lot to do to prevent monkeypox from becoming endemic in the United States.

“It is going to take not business as usual, but really actually in that emergency mode, accelerating and engaging and firing on all cylinders from the community to the federal level and from federal to global,” Martin said.

Titanji, who is Cameroonian and an expert in HIV drug-resistant viruses, said that she believed the monkeypox outbreak was a result of Western health experts neglecting diseases that originated in Africa.

“Because there is a lack of investment generally in neglected and emerging infections, that’s how we find ourselves in the situation in which we are now,” Titanji said. “With the interconnectedness of the current global landscape … we really need to move from the mindset of if it’s happening far away over there, then that is not our problem.”

Monkeypox is endemic in 10 countries in West and Central Africa, with repeated outbreaks occurring over the past three decades.

However, antiviral drugs that have the potential to help treat monkeypox are still primarily only available in European and North American countries, Titanji said.

“Vaccination is being rolled out primarily, again, in European and North American countries, and Africa, as well as South America do not have access to any of these resources,” Titianji said. “So while it is important to raise awareness of an emergency situation by declaring a Public Health Emergency of International Concern, those remain just words if it’s not followed by a concrete plan to actually make that to ensure that there is equitable distribution of the resources.”

News Editor | Eva Roytburg (she/her, 23Ox) is from Glencoe, Illinois, majoring in philosophy, politics and law. Outside of the Wheel, Roytburg is an avid writer of short fiction stories. In her free time, you can find her way too deep in a niche section of Wikipedia.