In his Farewell Address, President George Washington warned the American people about the dangers of political parties: “Constituted authorities … serve to organize faction, to give it an artificial and extraordinary force; to put in the place of the delegated will of the Nation, the will of a party.”

The goal of any political party is, in Washington’s eyes, “to make public administration the mirror of the ill-concerted and incongruous projects of faction, rather than the organ of consistent and wholesome plans digested by common councils and modified by mutual interests.” In other words, political parties impede the purpose of government.

Washington would be disappointed and quite possibly enraged if he could see his country today, 218 years later, where U.S. politics is organized largely along bipartisan lines. There is a left and a right. “Always in moderation” is meaningless in this system.

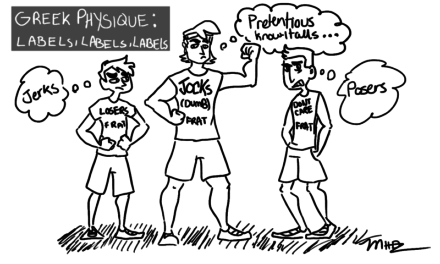

If a politician wishes to be taken seriously in this country, he must identify himself with either the left or the right. To be on the left, all you have to do is believe in social programs. If you are afraid of change, chances are you are on the right. As reductive as this seems, it is how the Democratic and Republican parties often delineate themselves.

Now, the terms left-wing and right-wing are pretty bland, and as any consumer knows, bland products do not sell on their own. Thus, the terms have been spiced up for more palatable American consumption. We have liberals on the left, conservatives on the right. There is hardly any logical basis for using these words as substitutes, but doing so affords politicians and political media the chance to more loosely interpret the nothingness that is U.S. politics into something that almost makes sense.

I think that U.S. politics today indicates how truly unpatriotic the average American is. For most of our history, we have been divided into political factions, each bent on promoting its own interpretation of the law. Such has been the pattern for human beings since the dawn of civilization. Washington and many of our other founders hoped to break that pattern, because they knew that political parties were, as Washington put it, “ill-concerted and incongruous.”

How did we repay them? Had they been the founders of any other country, they would be worshiped today as the nation-building prophets whom they were. Instead, we treat them like ordinary politicians, distinguished only by their presence in the drafting of our Constitution. We celebrate Washington but as an almost completely faded memory of the face of a dollar bill. We’ve reduced the Founding Fathers to flimsy archetypes from which the politicians of today can compare themselves with much ease. Or worse, we ridicule them.

When I hear people talk about President Thomas Jefferson, for instance, more often than not they bring up how Monticello was maintained by slave labor in attempt to undermine his credibility as a human being. They undoubtedly feel victorious in calling out the hypocrisy of a man who wrote that “all men are created equal” despite his ownership of slaves.

Slavery is wrong. The fact that I have to make such an obvious and widely accepted statement exemplifies another problem we face here in America: the fear of being politically incorrect. To be naturally disposed towards political correctness is one thing. To be so fearful of being politically incorrect that we shudder at the idea that somebody who owned slaves might have made some interesting points unrelated to his ownership of slaves is stupid and self-defeating.

Jefferson has become a victim of circumstance, and as a result, he is seldom referenced today. I find this deeply disconcerting, especially since I feel like his writings would resonate well with many Americans today, especially anybody who is wary of corporate America, disgusted by deregulation and remotely aware of the growing income inequality here in the U.S.

We are so bent as a nation on engaging in pointless bipartisan debates that have proven to do one thing only: deadlock Congress and prevent any meaningful legislation from being passed. Somehow we have convinced ourselves that this is the meaning of patriotism.

If patriotism means to completely disregard the legitimate concerns that our first president voiced in his Farewell Address, then I guess I’m a turncoat.

– By Erik Alexander

Erik Alexander is a College senior majoring in economics.