This story has been updated to add the opinions of those in the community

This year will become one of reflection, as Emory’s 19th president announced last Friday he will step down in August 2016. The past 12 years of University President James W. Wagner’s term saw record-breaking fundraising, major campus renovations and a completed 10-year strategic plan — but they were also marked by major academic cuts, the arrests of student demonstrators and an editorial that many found racially insensitive.

“You want to feel as though you’re running the race at top speed when you hand the baton off — not just stumbling into the box barely getting the baton to the next person,” he told the Wheel. “I feel that way. I feel very excited for Emory. And I have got to confess: I feel excited for me, too.”

The President said he made the decision, because he felt it is the right timing for Emory and for him, announcing the news during Friday morning’s meeting of the Executive Committee of the Board of Trustees and in a campus-wide email just after noon that day.

He said he came to his final decision over Labor Day weekend but began discussing his departure with John Morgan, chair of the Board of Trustees, and other advisers late last spring, according to Associate Vice President for Media Relations Nancy Seideman.

Wagner does not plan to seek a job at another university or institution. While former University presidents often serve on non-profit and for-profit boards, Wagner will spend a year without any employment, including part-time service on boards, according to Seideman.

Morgan told the Wheel that the Board of Trustees is already developing an “inclusive, open” selection process for Wagner’s successor. Morgan, who called for a standing ovation for the President at last week’s Board meeting, added that the Board was hopeful that it would have a few more years with the President.

In 2003, Wagner began a three-year rolling appointment that was reviewed and renewed annually by the Board of Trustees, according to Seideman.

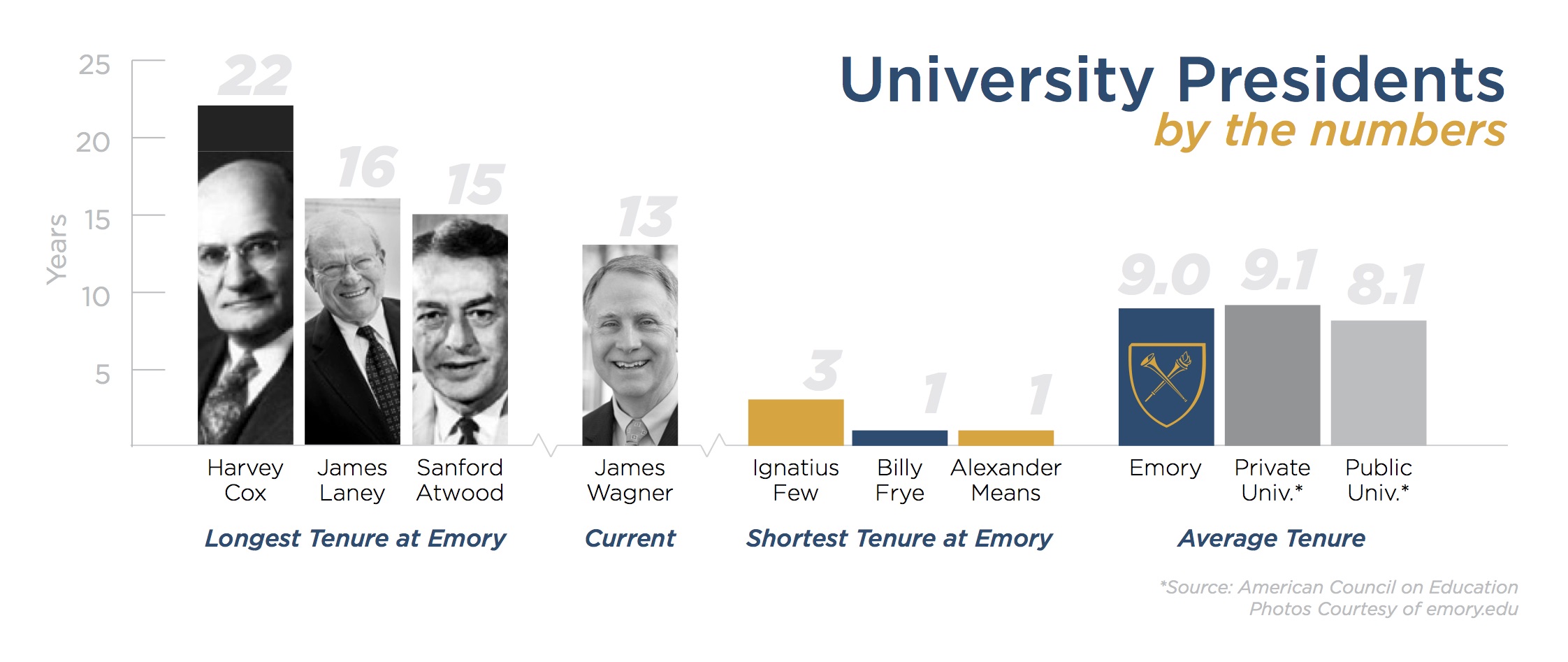

A dozen years later, Wagner finds that Emory is at a “crossroads,” perfectly-situated for a transition with the end of one of his top tasks: a $1.69 billion fundraising effort. At the heels of a new campaign that will last roughly eight years, Wagner said leaving in the middle of another fundraiser wouldn’t be optimal for Emory. University presidents, at Emory and in the nation’s private universities, stay in office for an average nine years.

On top of that, this year marks the end of Emory’s 10-year strategic plan, the University’s approach to become “a destination university, internationally recognized as an inquiry-driven, ethically engaged and diverse community.”

I feel very excited for Emory. And I have got to confess: I feel excited for me, too.

Wagner believes his school has accomplished that goal. For the first time in Emory’s history, the College received more than 20,000 undergraduate applications. The University has repeatedly been ranked by U.S. News & World Report as a top university but over the years has slipped to 21st among national universities.

Last year, the University received countrywide attention as it treated the first Ebola patients in the Western hemisphere. Students return every year to an incrementally transforming campus, including expansions and renovations to the Atwood Chemistry Center, Candler School of Theology, Health Sciences Research Building, Emory Point and more.

While Emory’s endowment increased nearly 15 percent between 2013 to 2014 and is now at roughly $6.7 billion, top 20 schools averaged an almost 18 percent increase in that same period.

Senior Vice President and Dean of Campus Life Ajay Nair agreed that Wagner has led Emory to become a “destination university.”

“We have arrived,” Nair said. “That’s in large part thanks to Wagner’s leadership in shifting the culture of Emory University in such a way … [that] all aspects of the University are strong. I think he leaves Emory better than when he found it.”

Granted, the moments of controversy under Wagner’s administration still ruminate in the memories of some Emory students and faculty. In 2011, police arrested several students demonstrating against the University’s food service vendor Sodexo. The next year, College Dean Robin Forman announced the closure and restructuring of numerous academic departments, igniting a series of protests and backlash.

“His presidency has been marked by a technocratic notion of what the University should be, dominated by the interests of the hard sciences and health center at the expense of the humanities,” former Emory journalism professor David Armstrong said.

In 2013, Wagner wrote an Emory Magazine editorial that cited the U.S. Constitution’s three-fifths compromise in an argument about the need for national and campus consensus, drawing immediate and widespread local and national criticism, faculty letters of discontent and campus protests. In response, the College faculty put forth a motion of “no confidence” in Wagner, which was rejected by 60 percent of the voters.

Noelle McAfee, director of undergraduate studies in the philosophy department and president of Emory’s chapter of American Association of University Professors (AAUP), acknowledged Wagner’s fundraising efforts but said his editorial “is still haunting him.”

“[The editorial] definitely created a divide between a lot of student populations and different segments of it with Wagner, and I thought a lot of people lost respect for him with that,” Goizueta Business School junior Michael Gadsden said. “His ignorance to me is just astounding … I think Wagner was really good at the back office stuff … but we need someone who really needs to put the students [first] and engage the community and bring it together.”

These points of Wagner’s administration don’t factor into his personal characterization of his legacy.

“We are at a moment in history, and I hope this is a passing moment in history, where we tend to define people by the things that disappoint us,” Wagner said.

Within the University’s ongoing lessons, such as those about social justice awareness, Wagner has had his own learning moments, he said.

After Wagner wrote an apology for his article involving the three-fifths compromise, many criticized his attempt to explain what he intended to say. That portion of the apology was later removed.

“I learned the difference between asking for forgiveness and asking to be excused,” he said. “I was asking to be excused for both my ignorance and insensitivity.”

Wagner looks forward to relieving himself of a 24/7 position that hasn’t allowed him to be open about many of his personal opinions. But, more than anything, he said he will miss the people who surround him.

A couple years into his term as president, a student asked Wagner about trick-or-treating at his home — the Lullwater House, an iconic Emory destination tucked over a half mile deep in a nature preserve on the edge of campus.

For the next half dozen years, less than a hundred students trekked the dark path to Wagner’s home every Halloween for casual conversation and a taste of his wife Deborah Wagner’s homemade cookies.

All of a sudden, the Wagner’s were overwhelmed with student trick-or-treaters.

“It must have gotten on some bucket list,” he said.

The night has now become an Emory tradition and a nightlong production, with full-sized candy bars and a capella groups welcoming students.

“It’s an endearing [memory],” Wagner said. “Something that I will remember about this place.”

This time next year, the home will belong to someone new, someone Wagner hopes shares his passion for higher education and liberal learning.

“I understand the wonderful platform that Emory provides,” he said. “If they do, they will instantly also develop an affection for this place.”

Executive Editor Rupsha Basu, Managing Editor Zak Hudak and Editor and Chief Dustin Slade contributed to this report.

This article was updated on September 12 at 11:46a.m. with updated graphics. “Embroiled in the controversy” is now replaced by “Wagner publishes controversial article” on the timeline graphic.

2015-2016 Executive Editor Karishma Mehrotra is a College senior and has been interested in journalism since her freshman year in high school. Her major is journalism and international studies with an unofficial minor in African studies. She became a writer for the news section of the Wheel when she began college and became news editor that year. She has interned at CNN, The Wall Street Journal, the Boston Globe, USA Today, the Atlanta Journal-Constitution, Palo Alto Weekly and KCBS Radio. She studied abroad in Ghana last semester, which inspired her to join the African dance group on campus, Zuri. She recently worked as a tutor at the Writing Center. She is also a Dean’s scholar.