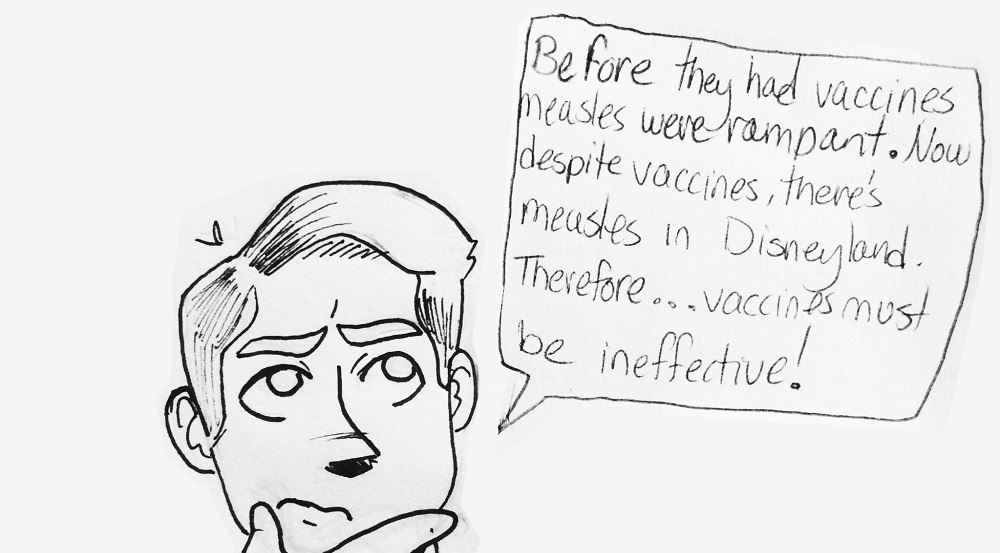

The recent outbreak of measles in Disneyland highlights the unprecedented rise in cases of measles and introduces a frightening possibility: if measles can come back, so can polio and tuberculosis. The prospect of their return makes the issue of addressing misconceptions about vaccines ever more important.

Last week, the Wheel published an editorial discussing the measles outbreak and vaccine controversy, where the writer, Maya Lakshman, notes “the lack of information provided about vaccines and the ways in which vaccines are administered.”

Fortunately, this is not true. The World Health Organization, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, the National Institute of Health, UNICEF, the Gates Foundation, the American Medical Association and reputable peer-review research journals agree that vaccines are beneficial and important to protecting individuals from disease. The information regarding their safety and efficacy are readily available to the general public on the websites of these trustworthy organizations. For those who are curious, decades of research provide insight into how vaccines work as well as their components.

[quote_box name=””]

While science’s greatest triumph in medicine was the development of vaccines, the fight is far from over.

[/quote_box]With this well-established research translated by health officials for the public, Lakshman must be careful in stating “the public has been split on the issue of vaccines” when it is quite the contrary. A new national survey by the Pew Research Center found that over 80 percent of adults in the United States view vaccines — such as the measles, mumps and rubella (MMR) vaccine — as safe for healthy children. Thanks to the efforts of public health officials, researchers and physicians, most of the air has been cleared about the safety and necessity of vaccines. However, the story was entirely different 17 years ago. In 1998, Andrew Wakefield published a study in The Lancet, a prestigious medical journal, claiming to have found a connection between autism and the MMR vaccine. Upon discovery that he falsified data, his paper was retracted and his medical license was revoked. Nevertheless, the damage was already done, and the anti-vaccine movement gained significant momentum.

This is where the other 20 percent in the Pew survey come into play. Half of that group believes vaccines are not safe, while the other half are not sure. It is urgent we convince those on the fence of the necessity of vaccines in order to achieve a vaccination rate of about 90 percent, which will be just enough to achieve what is known as herd immunity. Herd immunity revolves around the idea that when a large percentage of a population — “the herd” — is vaccinated, paths of infection are blocked, thus limiting the spread of disease.

This approach protects the entire population, and most importantly, those who are too young or too sick to be vaccinated. With over five million babies born every year in the United States, they face a risk should measles enter the community. Of course, when enough individuals are not vaccinated, holes begin to appear in herd immunity, which increases the risk of disease transmission. As demonstrated by the Disneyland measles outbreak that has led to cases appearing across the country at increasing levels, herd immunity for measles is beginning to collapse.

History has already illustrated the success of vaccination and herd immunity with the eradication of smallpox. A similar approach is being used for measles as well as other diseases. Measles was supposed to be a disease that we only read about in textbooks. Paradoxically, the success of vaccines may have contributed to the rise of the anti-vaccine movement. Most of the diseases that vaccines protect against have been pushed into hiding, resulting in generations of people who have never personally experienced the devastation they can cause. With the luxury of forgetting these diseases, it becomes easier to fall prey to fear and begin refusing vaccines, making it ever more important for scientists and doctors to educate the public on this matter.

Lakshman does bring up a valid point regarding the need for “a better … line of communication between [physicians] and patients.” However, the use of a single negative experience does not warrant the disaccreditation of the health care system or presumption of a “vaccine controversy.” There is no controversy; instead, we face the threat of misinformation that must be readily addressed by physicians and researchers alike.

We, the Emory community, have the responsibility to lead the way in this endeavor. As one of the leaders in health sciences education and research, we need to actively communicate with the public and engage in dialogues to break down the boundaries between the experts and everybody else.

While science’s greatest triumph in medicine was the development of vaccines, the fight is far from over. We now face an even more difficult challenge in preserving and garnering public support for vaccine programs long after these diseases have largely vanished from our everyday lives. We have carried out the research. Now we need the trust.

Roger Tieu is a College senior from Rochester, New York.