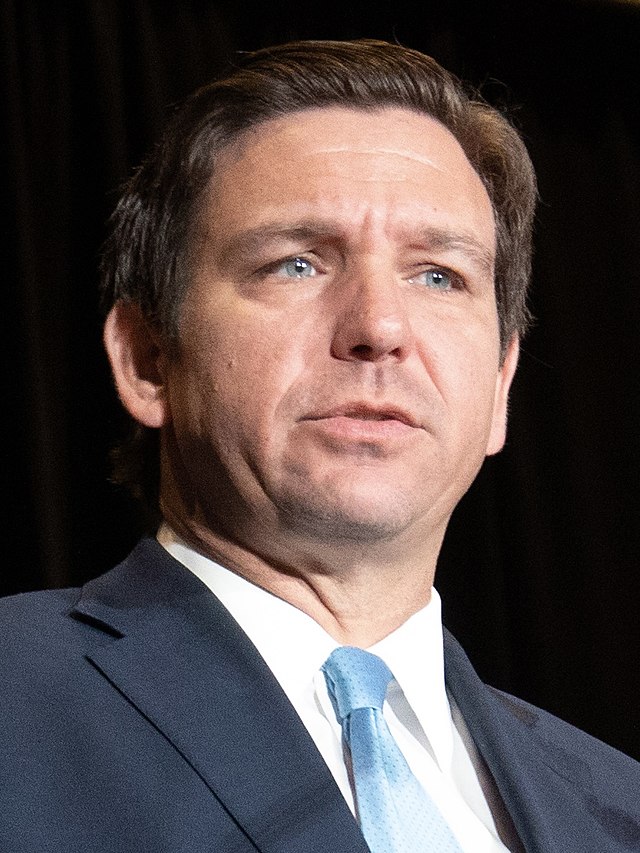

Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons/Office of Ron DeSantis

Florida Gov. Ron DeSantis has spent his last four years developing a national profile as a right wing hardliner whose traditional brand of conservatism contrasts with former President Trump’s identity-based populism. He has become a darling of the right, with national media deeming him a “superstar” and predicting he can assemble a “Reagan coalition” in 2024.

One of the central pillars of DeSantis’ platform is an effort to dismantle a system of “indoctrination” in U.S. schools. Several pieces of legislation have glided through both Republican-held chambers in Florida and onto the Governor’s desk in recent months, including the “Stop Woke Act” and the “Don’t Say Gay” bill. DeSantis’ most recent initiative rejected an AP African American Studies class which he claimed would advocate for “abolishing prison.”

The theory behind these measures is that the U.S. is currently placing too much trust in teachers to avoid ideologically driven conclusions and political agendas in the classroom, resulting in biased curricula. However, taking legal action to prevent bias simply shifts that trust onto politicians who benefit directly from the advancement of political agendas. Teachers’ motive to push an ideology is almost always indirect, while lawmakers depend on political agendas to maintain their status and salaries. In other words, education usually comes from teachers, and indoctrination usually comes from government. This sort of effort signals a new, corrosive form of government overreach establishing itself at the heart of DeSantis’ Republican party.

As Ronald Reagan, one of the right’s most iconic “superstars” famously put it, “The nine most terrifying words in the English language are ‘I’m from the government and I’m here to help.’”

DeSantis’ “Stop Woke Act” takes an exclusionary approach to shaping curricula, forbidding teachers from discussing a set of social concepts that are considered damaging and prejudiced in the classroom. Most of these forbidden concepts are already shunned in education, including teaching that some races are “morally superior to others.” However, these stipulations become more vague as one reads further into the bill.

For example, the bill forbids teachers from suggesting that certain “virtues” such as “excellence” and “racial colorblindness” are “racist.” “Colorblindness” has long been scrutinized as a social justice ideal, considering that disregarding the role race plays in society ignores a long history of systemic racism. Equating this questionable virtue with “excellence” and entangling any criticism of it with accusations of racism will likely lead to avoidance of conversations about race in general. Because of its vagueness (among other constitutional issues), the bill was recently struck down by a Florida judge.

Just a month prior to the passage of the “Stop Woke Act,” the infamous “Don’t Say Gay” bill was signed into law, prompting national criticism and condemnation. The function of this bill can be summed up in its preamble, which states its purpose as the prohibition of “classroom discussion about sexual orientation or gender identity.” There is some disagreement about how exactly this would manifest, but advocates of the bill claim it is aimed at protecting students from sexual information that may be confusing or disturbing at a young age. However, the bill’s explicit focus on LGBTQ teachers suggests some inherently inappropriate or taboo element to these sorts of relationships, and threatens to scandalize conversation that would be perfectly normal in a heterosexual context. For example, an elementary school teacher simply referring to their same-sex spouse may be seen as a violation of the law, despite a long accepted practice of discussing basic family dynamics with students.

In order to assess the implications of this legislation, it is important to consider the meaning and morality of a political agenda in the classroom, and imagine what sources are most likely to produce this bias.

First, a reminder that the difference between education and indoctrination is that indoctrination trains people to accept a certain set of beliefs uncritically. To be uncritical (and disregard information that may lead to an undesired conclusion) is usually a symptom of some ulterior motive that supersedes the desire to understand an unbiased truth. This serves as a working definition for a political agenda. An agenda is uncompromising; it is concerned only with a goal, like ideological conformity for the sake of political obedience or consensus. By this definition, a political agenda is an educational contaminant. DeSantis’ stated ideal of a curriculum of “facts” rather than ideology must reject any editorialization on the part of teachers with an agenda in order to ensure that students remain critical, rather than indoctrinated.

An ideological statement is characterized by a synthesis of several facts, leading to a broader moral conclusion, often considering alternatives and historical implications. It may be hard for students to determine when a teacher has veered into ideological territory. This means that political opinion may go unidentified and be conflated with fact, or, if identified, may throw underlying facts discussed into question because of the impression of a general political bias. These statements are also a warning sign that an agenda may be at play. However, just because these assertions can be defined does not mean they can be prohibited, because reverse engineering legislation to forbid ideological conclusions may end up stunting teachers’ ability to relay underlying facts.

For example, let’s say a teacher is giving a lesson on how capitalism incentivizes companies to use cheap labor from countries with fewer labor protections. This seems like a factual assessment of cause and effect. Let’s say the teacher then makes a blanket statement that because of this, “capitalism is harmful.” This seems inappropriate because the statement is promoting an ideology or agenda. However, if legislation stated that teachers must not make claims like “capitalism is harmful,” then that underlying fact about incentives toward cheap labor (which, on its own, does serve as evidence that capitalism is harmful) is legally questionable and may be disregarded altogether.

Bias in schools is one of the many issues too delicate to be handled by the government. Its broad application and crushing enforcement is too blunt to untangle each individual knot of ideology within a teacher’s worldview. DeSantis must know this. To legislate classroom discourse according to ancient conceptions of pure relationships or vaguely worded virtues that crush and confuse reasonable conversation about the history of race in this country is a step towards indoctrination, not away from it.

Justin Leach (25C) is from Wayne, Pennsylvania.

Justin Leach (25C) is from Wayne, Pennsylvania.