It was an attack that would leave 11 dead and a free world scarred.

It tainted the joy of the New Year, spreading fear and hatred in place of the hope and excitement that rolled in with 2015.

The shootings were rampant but focused, targeting Charlie Hebdo, a satirical weekly magazine and a name that few outside of the country of France had even heard of prior to Jan. 7.

Charlie Hebdo was known for its often offensive publications, which frequently depicted religious figures in compromising or unconventional situations. Before the attacks, the magazine had run a series of issues featuring the Prophet Muhammad in unconventional situations.

On the morning of Jan. 7 of this year, two masked gunmen stormed the offices of the magazine, ultimately emptying their firearms and leaving 11 dead and 11 injured. Immediately following the shootout, the men were reported to have shouted “Allahu Akbar” (Arabic for “God is [the] greatest”).

The next two days yielded hostage situations and similar shootouts where an additional five victims were killed and 11 were wounded.

Although the magazine faced backlash for years following its first publication, no single event or complaint exceeded the magnitude or aftermath of this one.

The basis for the attacks was presumed to be a result of an outrage over the magazine’s depictions of Islam. Before they were killed, the gunmen identified themselves as belonging to a branch of Al-Qaeda.

In the days that followed, the entire world rallied in support of France and the satirical magazine as “Je suis Charlie” (French for “I am Charlie”) circulated throughout social media. The next week, Charlie Hebdo managed to publish another issue, this time depicting the Prophet Muhammad with tears in his eyes, holding a sign scribbled with the words “Je suis Charlie.” The byline reads: “All is forgiven.”

The two perpetrators were French citizens, born and raised on the very grounds they so hatefully targeted. This was not a raid from an unknown, outside force. This was not an attack sanctioned by a distressed or broken country. The men who tried to destroy Charlie Hebdo were French; they were educated in French schools and grew up surrounded by an aura of equality, freedom and democracy. What this implies about the nature of nationalism and a country of mixed races, cultures and religions is a conversation of its own.

Today, almost two months after the shootings and the deaths of the two perpetrators, it is becoming clear as to exactly what the Charlie Hebdo attacks mean to history and to the modern world.

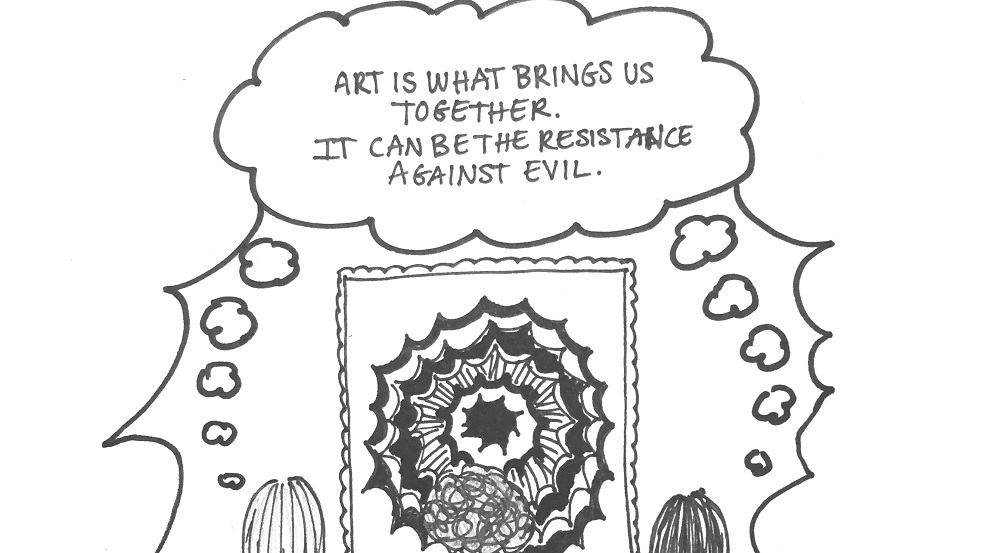

Primarily, the Charlie Hebdo incident has brought about a global consensus regarding the importance of the freedom of speech. Over time, “Je suis Charlie” came to mean more than just a statement against the attacks. It represented the right to express opinions and thoughts. It represented the ideals of a free and open world. It represented an unalienable human right and the basic entitlements of the human population.

Above all, it showed the world that there is no need to validate a pair of men who believed that destroying human lives would consequently destroy open expression.

In addition, the satirical magazine set a landmark example in regards to how terrorist attacks should be viewed. By depicting the Prophet Muhammad crying and bearing the same three words the remainder of the world held on to that week, the magazine directly implied that the attacks were not aligned with the understanding of the Islamic faith.

This is a standpoint that should be taken in regards to any attack or incident that may be coincidentally linked to a religion or a faith. At times, it is hard to separate the characteristics of the perpetrator from his inhumane actions; but, as the cover of Charlie Hebdo did following the attacks, it is very important to do so.

As was the case with 9/11 and many other attacks around the world, the shootings were not the result of a singular religion but of delusional and misled men who used Islam as a façade to validate their murderous rage.

Most importantly, the Charlie Hebdo shootings highlight the continued importance of having opinions in the modern world. As humans, we are entitled to feeling different ways about particular occurrences or incidents.

Charlie Hebdo reiterated the fact that regardless of what the stance may be, the world is and always will be in support of sharing it.

Still, regardless of these positive byproducts of Jan. 7, the attacks also bring to light one main question that remains unanswered: Where do we draw the line?

What are the limits to the freedom of speech? The Charlie Hebdo magazine went to long lengths to depict characters and symbols that certain religious and cultural groups found to be extremely offensive. But, if we limit journalism to be courteous of all people, would there be anything left to write? Would there be anything left to say? Doesn’t all writing that takes a solid stance ultimately oppose something?

Earlier this week, a friend of mine, Trisha, lost her father to Islamic militants who savagely stabbed him to death; he was a prominent writer and journalist, speaking out in support of atheism and the acceptance of all religions.

Although she had the right to, Trisha never attributed the attacks to the faith of the people who initiated them. Instead, she stood by her father’s platform, spreading the phrase “words cannot be killed” on his behalf.

As with the Charlie Hebdo incident, the attack on Trisha’s father emphasizes the level of atrocity certain groups of people are willing to reach in order to shut down a lasting concept such as free speech.

People should not have to suffer because they feel a certain way. People should not have to die because they want their voices to be heard. Something needs to be done.

Ultimately, the world needs to continue to stand against acts of hate that threaten or endanger what freedom and universal understanding represent.

And the free countries of the world need to continue to unite in the face of battling terrorism together.

Sunidhi Ramesh is a College freshman from Johns Creek, Georgia.

“By depicting the Prophet Muhammad crying and bearing the same three words the remainder of the world held on to that week, the magazine directly implied that the attacks were not aligned with the understanding of the Islamic faith.”

++

“There is an inspiration for attacks like those on writers, cartoonists, and film-makers: France’s Charlie Hebdo

journalists; Amsterdam’s Theo van Gogh; Denmark’s Kurt Westergaard, Carsten Juste, and Flemming Rose,

and Sweden’s Lars Vilks — as well as the assassination attempt on the Nobel Prize winning Egyptian

novelist Naguib Mahfouz and the fatwa for the murder of the British writer Salman Rushdie.

The inspiration for this behavior is not that the Prophet Muhammad was lampooned or criticized or mocked. The inspiration for this behavior is that Muhammad himself would have ordered or approved such attacks as revenge for

assaults on his honor.”

“… it is hard to separate the characteristics of the perpetrator from his inhumane actions; but, as the cover of Charlie Hebdo did following the attacks, it is very important to do so.”

++

What you are really saying here is this: Let’s ignore reality, Let’s pretend the endless barbaric attacks committed by Muslims and in the name of Allah are not connected to Islam’s core tenets of violent jihad, Islamic supremacism and are not patterned on Mohammed’s example. Instead let’s be PC and pretend all religions are the same even though in our hearts we know they are not.

++

You get an A+ in your PC course.

Let’s pretend the following information about Mohammed does not exist and let’s also pretend I run the risk of being killed by Muslims for speaking honestly about their religion including their sadistic prophet:

Dhu al-Faqar

was one of the 9 swords owned by the Islamic Prophet Muhammad, and with it he

claims he was “made victorious through terror.” Appropriately named “cleaver of

vertebrae,” the ancient weapon was used to butcher his enemies who insulted

Islam.

Islam also says that if you kill one man, you have killed of of mankind. The religion is not inherently bad. Just like there is constant war in sub-saharan African, There is not a constant war in the mid-east due to both internal and external reasons.

So nice to know how much Islam rejoices life. Lol

You, my friend, are a racist.

Do you really have to call me your friend? Who’s kidding who?

Well written article. I wonder what will be the next article

in your mind.