On Emory University’s Atlanta campus lies the 25-acre Yerkes National Primate Research Center. The thriving center of biomedical and behavioral research has existed since 1930 and is a research hub home to approximately 1,000 nonhuman primates.

It’s also named after one of the most prominent eugenicists of the 20th century.

Robert Yerkes spent decades conducting racist research advocating for the sterilization, isolation and murder of those who weren’t socially “useful.” And his name is just one of several with legacies marred by racism that continue to hold places of prestige on Emory’s campus.

In 2020, University President Gregory Fenves appointed the University Committee of Naming Honors to review contested honorary names. The committee submitted a report to Fenves in May 2021 recommending to remove the names of L.Q.C. Lamar, Robert Yerkes, Atticus Haygood, George Foster Pierce and Augustus Longstreet from all honors.

Fenves only acted on Longstreet, renaming Longstreet-Means Residence Hall to Eagle Hall and Longstreet Professor of English to Emory College of Arts and Sciences Distinguished Professor of English.

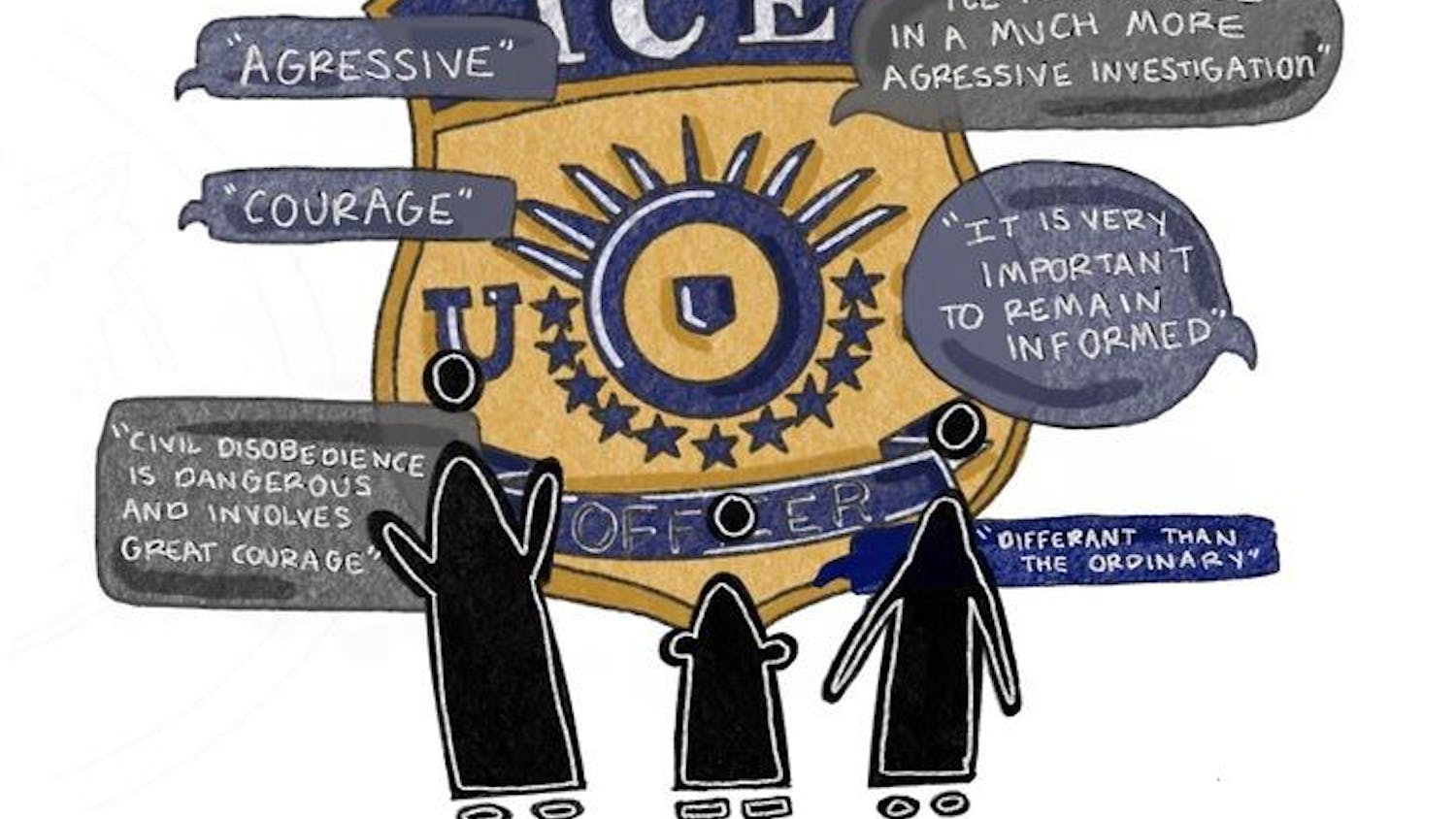

A group of alumni, faculty and students — dubbed the Emory Community Members for Historical Accountability — have advocated for name changes to the Research Center and the L.Q.C Lamar professorships. The group said it sent multiple letters since May to Fenves requesting to remove controversial names.

Several group members, including Professor of Law George Shepherd who published an article and emailed Emory officials advocating for the removal, told the Wheel that Fenves has not responded to their requests.

Assistant Vice President of Emory Communications and Marketing Laura Diamond wrote in a Feb. 11 email to the Wheel that Emory is “actively evaluating the recommendations of the University Committee on Naming Honors, consulting with experts and considering the perspectives of Emory students, faculty, staff, leadership, and alumni.” She said Fenves will update the community by the end of the semester.

Aside from the Yerkes center, the group took issue with two professorships in Emory’s School of Law named after Associate Justice of the U.S. Supreme Court Lucius Quintus Cincinnatus Lamar (1845C). Lamar was a slave-owner and a leading figure in Mississippi's secession from the Union during the Civil War.

Currey Hitchens (09L), a leader of the group, said Fenves’ decision to remove Longstreet’s name and not others was “baffling” because names in professorship titles like Lamar’s could easily change.

“There's a lot that goes into an actual change of this sort, including consulting with experts and considering perspectives of students, faculty, staff, leadership and alumni,” said Professor of Law Fred Smith Jr., who chairs the naming committee. “[Fenves] just reached that conclusion more quickly than he reached other conclusions, but he's still actively evaluating the recommendations.”

Jason Esteves (10L), another member of the group, said such a response “will not suffice” until the administration decides to remove other names.

“Lamar was a slave owner, he was leading secession,” Esteves said. “It's still unclear why we wouldn’t apply the rule across the board versus picking and choosing who to honor as a University.”

Contending with Yerkes’ and Lamar’s legacies

In 1941, as the Nazis murdered millions of Jewish people, Yerkes wrote in the Journal of Consulting Psychology that the U.S. should follow Nazi Germany in its “human engineering” efforts.

“Nazis have achieved something without parallel in human history,” the article read. “What has happened in Germany is the logical sequel to psychological and personnel services in our own army in 1917-1918.”

That same year, Yerkes advocated for the “elimination of the biologically unfit” and argued that providing resources for disabled people was an unnecessary economic waste.

He wrote in Symposium on Recent Advances in Psychology, published by the American Philosophical Society, that if a person’s “being held no promise of complete, serviceable biological development … it would seem socially defensible that his life should be ended gently.”

His writings greatly influenced the U.S. eugenics movement, which involved forcibly sterilizing 64,000 people.

In 1956, Emory agreed to assume ownership of the primate research center Yerkes started, just 15 years after he published his support for the killing of the disabled.

Director of Yerkes National Primate Research Center Paul Johnson wrote to the Wheel that he appreciated the committee’s report and took the concerns seriously, but it was “difficult to give a precise timeline at this time.”

The historical accountability group wrote in a July 7 letter to Fenves that Lamar championed white supremacy through means such as negotiating the Compromise of 1877, allowing white southerners to restrict Reconstruction in the South.

Lamar also supported the Dawes Act, which allowed the U.S. government to seize 100 million acres of Native American land.

Though the University removed Lamar’s namesake from the official Emory law school name, group members cited these as reasons not to support him.

“He was a traitor against our nation, he was fighting to continue to enslave Black peoples because he believed that there were less than others,” Hitchens said. “He fought for that even after the Civil War.”

Continuing to honor Yerkes and Lamar is embarrassing to Emory’s legacy and antithetical to the University’s values, Shepherd said.

“We just need to think carefully about who Emory wants to honor,” Shepherd said. “Does it want to honor racist, antisemitic people?”

Esteves said there were ways to recognize history without honoring men who contributed to historical atrocities.

“You can honor them by studying their history and studying their accomplishments, and by doing that, inherently recognizing what they’ve done right,” Esteves said. “To have the distinction of having a program or a building named after them, that is amongst the highest of honors, and that should be bestowed on people who represent the values of that institution.”

The Atlanta perspective: Confederate emblems and Atlanta’s ‘city personality’

Emory’s attempt to reckon with its Confederate past comes after the broader Atlanta community sought to rename streets and take down monuments glorifying the Confederacy.

Professor of Practice at Georgia State University Douglas Blackmon lived only a block away from the Confederate monument during the neo-Nazi attacks in 2017.

“We have a history that is deeply rooted in terrible things that were intent on destroying American democracy,” Blackmon said. “These were traitors against our country of today, in order to preserve the cruel system that moral people all over the world already knew was wrong.”

The tragic events in Charlottesville reinvigorated discussions about keeping relics of Confederacy through names, prompting the Atlanta City Council to form Atlanta’s Confederate Monuments Advisory Committee. That committee developed “recommendations for moving forward with city-owned Confederate-related monuments and street names.”

However, the committee only existed for six weeks as a short assignment at the end of former Atlanta Mayor Kasim Reed’s second term.

The construction of Confederate monuments and street dedications, Blackmon said, occurred during the height of post-war grief and the beginnings of what became a large-scale white supremacist campaign. For instance, in the 19th century, Confederate Avenue was constructed in southeast Atlanta and led directly to an area associated with old Confederate soldiers’ homes. That street became United Avenue in 2019 after the monument advisory committee recommended a name change.

The committee also recommended that Atlanta form criteria to determine if a street name should be changed. That criteria has yet to be changed.

People have turned a more “critical eye” to monuments that weren’t clearly tied to the Confederacy in recent years, Associate Professor of Political Science Andra Gillespie said.

“This is an opportunity to learn more about our history, and learn more about the flaws and the blind spots of people who lived before us,” she added.

President of the Atlanta History Center Sheffield Hale began working on Confederate monument issues in 2016 after a white supremacist killed nine churchgoers in Charleston, South Carolina in June 2015.

Hale became a member of the Confederate Monuments Advisory Committee in 2017 to engage the city residents in meaningful conversations. Some controversial monuments are protected by state law and are not under the committee’s purview.

“It’s really hard to have a conversation when there’s not truly an option,” said Claire Haley, the Atlanta History Center’s vice president of public relations. “Even if they go through a thoughtful process and determine that it’s not appropriate for the community, they can’t do anything about it.”

Blackmon said the state law did not always seem to be enforced, noting that the state did not take action after a monument was removed in Oakland Cemetery.

Hale helped evaluate the Peace Monument in Piedmont Park, erected in 1911 as a reconciliation effort between the North and South that excluded Black people amid the restrictive Jim Crow era.

“We should preserve certain monuments because they are markers of important things that happened,” Hale said. “On the other hand, none of the African Americans had a vote at that time about whether it should be there or not.”

Hale said that when the committee suggested it be removed, Georgia law halted any further action. The best they could do was install panels contextualizing the history behind the structure.

Blackmon said some opposition to the committee stemmed from the inconvenience of renaming businesses.

During committee hearings, however, Blackmon said that many opposers supported the “lost cause” mythology and made arguments that taking down monuments would erase history.

“Many people internalize it as an attack on their identity as white people,” Hale said. “We’re not trying to say anything disparaging about their ancestors, we’re just trying to deal with this monument and what it means today.”

Such opposition, Blackmon said, supports the fact that Atlanta is still surrounded with endless reminders of the city’s role in preserving slavery.

Blackmon said Atlanta has developed a sensibility that urges people to ignore what the monuments actually mean, because it’s so unpleasant. However, he said the current conversation is an opportunity to “awaken” people.

“You could easily arrive in Atlanta and see all these street names and say that it’s a bastion of white supremacy,” Blackmon said. “But that’s not what Atlanta is, and we shouldn’t encourage people to somehow be OK with this depiction of our city.”

Correction (2/18/2022 at 6:07 p.m.): A previous version of the article stated that University President Gregory Fenves appointed the University Committee of Naming Honors to review contested honorary names in 2019. He in fact appointed the committee in 2020.