Among the sins of the art world, few are as awful as intentional exclusion and marginalization of minorities. For centuries, both the medium of textiles and the narratives of people of color have been systematically excluded from the top-tier of the art historical canon, which has largely been dominated by oil paintings and classical sculpture created by white European men. Recently, this pattern has begun to change, and a particularly important exhibition in that transition is the “Bisa Butler: Portraits” exhibition at the Art Institute of Chicago, open through Sept. 6.

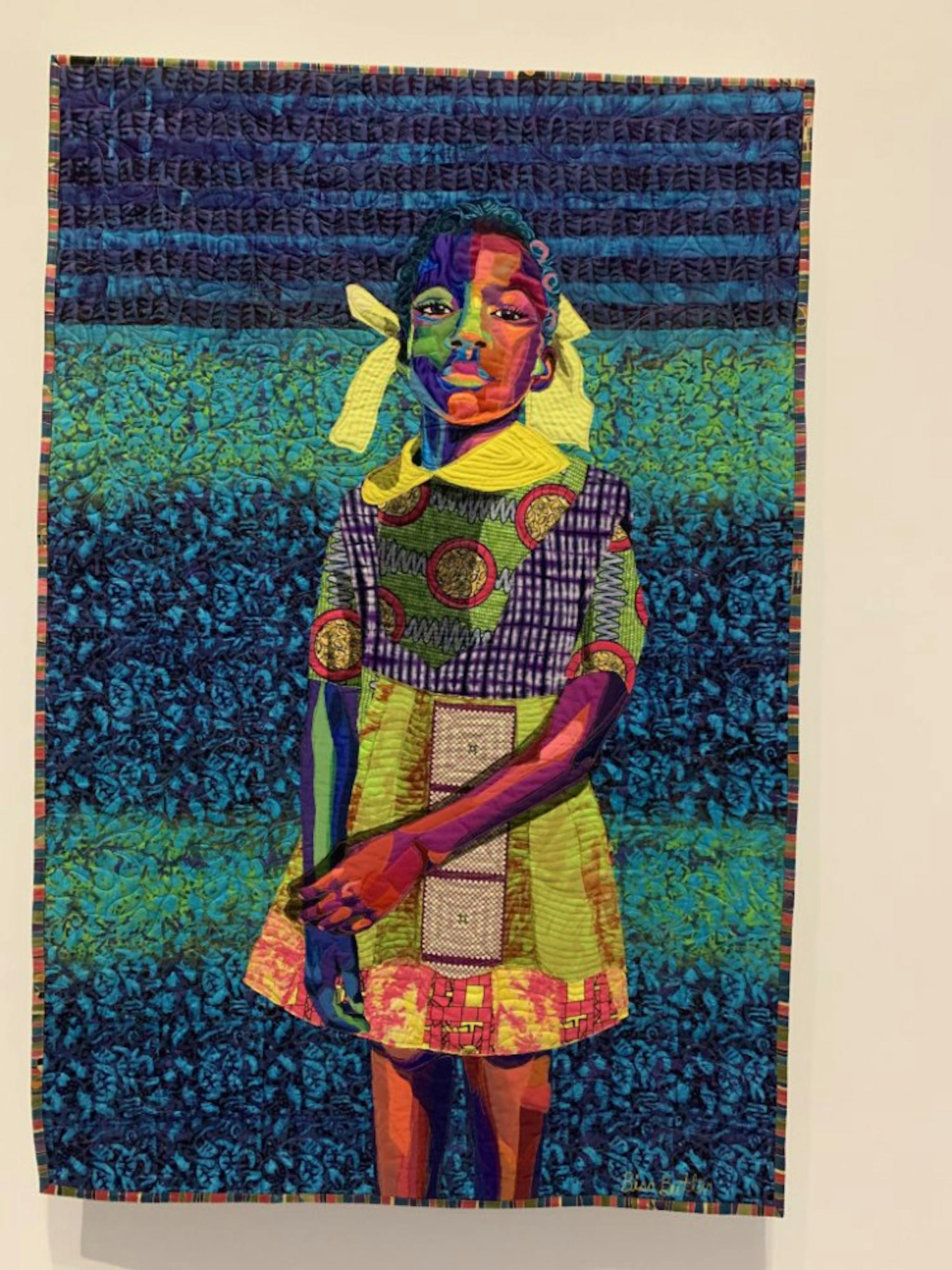

Butler is known for utilizing the scale, detail, layering and depth of fabric to create visual and emotional dimension, depicting Black Americans of all ages, time periods and perspectives. She has portrayed a wide range of historical and contemporary Black narratives, ranging from a stylish newlywed couple in the 1930s to her close friend, a Jamaican immigrant depicted in “The Princess.” These narratives are traditionally marginalized in American society as a whole and especially in the world of “high art.”

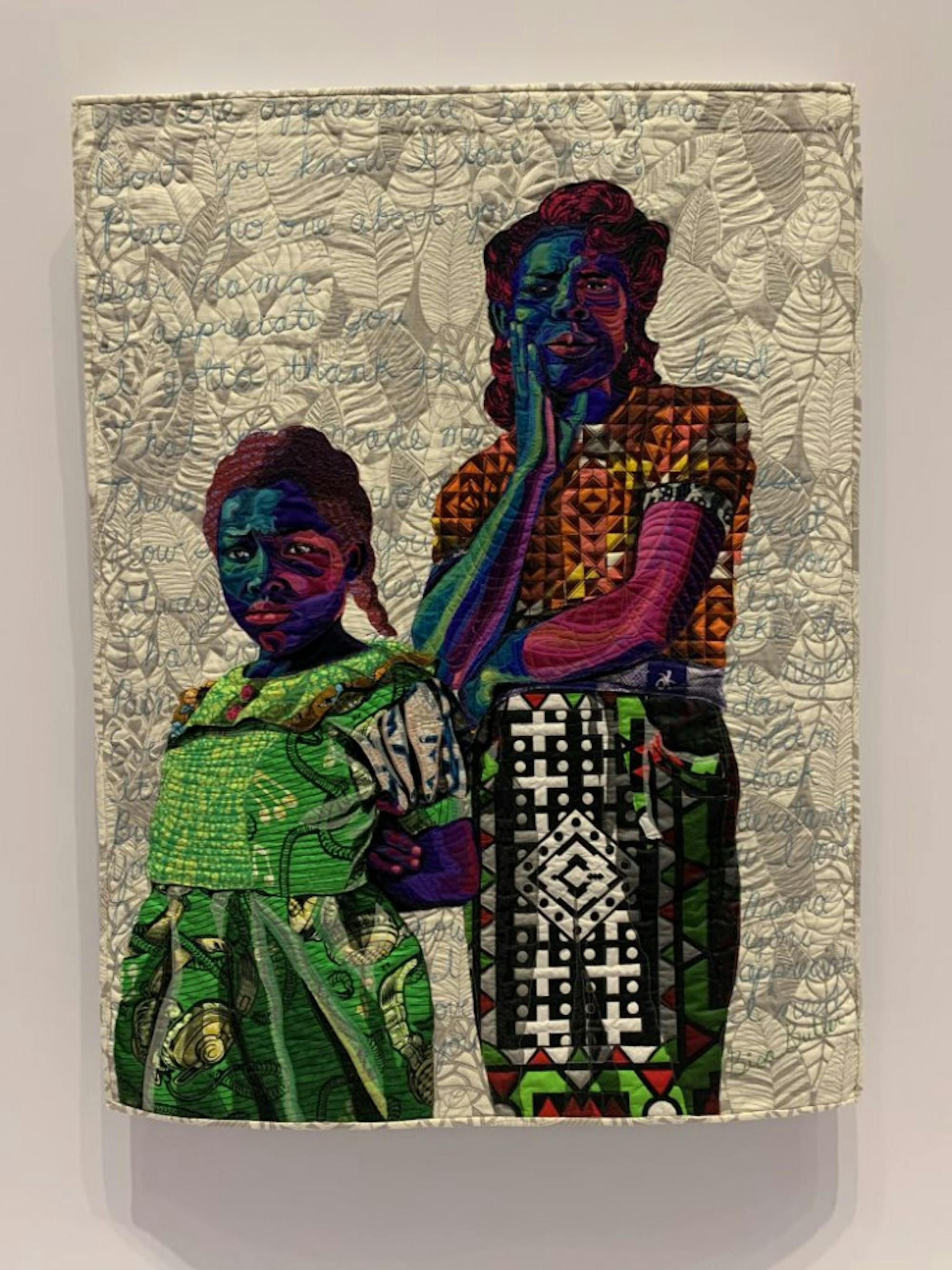

Butler learned her craft from professors and artists who participated in the AfriCOBRA movement, a Chicago-based artist collective that focused on solidarity and self-confidence in the Black community. These teachers emphasized a responsibility to highlight the strength of Black Americans, and as Butler explains in the exhibition introduction video, they believed in not simply saying “look at our struggles,” but also “look at what we can do.” In each of her artworks, the subject stares back with determination, and Butler depicts them with the boldest of colors and the most impressive of techniques. “Dear Mama,” was one of the most unflinchingly emotional examples of Butler’s portraiture strength. The child’s cursive handwriting in the background outlines a thank you letter to her mother, and the two figures of mother and daughter appear to look toward their futures with an equal expression of pessimism and optimism. Butler outlines the strength in being able to see danger and still move forward.

While Butler was initially trained as a painter, after making a quilt to honor her grandmother, she decided to continue exploring textiles. Butler found that fabric offered a certain opportunity for dimension and scale beyond the constraints of painting. This medium also reflects the quilt-making practices of enslaved Africans, and Butler often includes traditional African textiles, like Kente cloth, in her work. Having just visited the Arts of Africa galleries at the Art Institute and seeing similar motifs and textiles between both galleries, I found this choice particularly resonant. One of Butler’s first textile portraits was of her paternal grandfather whom she never met, and she used her grandmother’s African fabrics to make the portrait. In that way, Butler’s portraits represent how African ancestry and culture has informed the legacy of Black American art and life in the United States — a sentiment apparentin her artist's statement where she explains how her subjects are "adorned with and made up of the cloth of our ancestor."

In that sense, Butler connects to an entirely different art historical canon and perspective, one that centers Africa in the narrative of art. She uses common motifs and artistic practices from the continent as inspiration, as opposed to common, predominantly white, Western classical inspirations. Butler reflects some classical ideas of Renaissance ornate textiles, but disrupts the Western canon by including ancient Kente cloth and emphasizing modern, diverse subjects. Her textiles are seemingly of the past, the present and the future.

Each of the thirty artworks in the gallery are paired with a song on a completed Spotify playlist for the exhibition, which is an innovative, modern approach to the complete sensory experience of a gallery. The songs ranged from Beyonce hits to Muddy Waters blues tunes, immersing listeners in an era and energy completely separate from the space around them. “The Princess” was paired with “BROWN SKIN GIRL,” and the song shared the same vision of hope with an underbelly of sorrow that you can see in the eyes of Butler’s subject, transporting you into the heart of the textiles.

The Spotify playlist, the diverse subjects of Butler’s textiles, the descriptive gallery labels and the vastly unique visual experience of vivid, yet realistic textile portraits created an overall more accessible and intriguing gallery experience than I have seen in most major museums. As I looked around the exhibition, I saw people of all races and ages, some in families talking about the gallery and others sitting quietly by themselves listening to the playlist. The space felt free — free for people to be who they were, free to walk through as they wanted and free to take in the art in the ways that worked best for them. The exhibition, especially in tandem with the playlist, felt like an artistic experience that anybody would want to participate in; it was neither elitist nor confusing, but deeply moving.

Ultimately, Butler’s use of an underrepresented medium to reveal underrepresented narratives in portraiture is quite poetic in its own right and merits not only this grand solo exhibition, but a lifetime of respect and inclusion in the art historical canon. This exhibition is a step in the right direction for the future of more equitable, immersive and accessible museums.

This article is part of an ongoing column on underrated and unsung visual artwork. Read the other articles here.