Jimmy Carter, the 39th president of the United States who began his journey to the White House as a little-known governor from Georgia, died on December 29. At 100, he was the oldest and longest-retired president in U.S. history. Carter served 41 years as a distinguished professor at Emory University.

Carter’s son, James Carter, confirmed to the Atlanta Journal-Constitution that the former president died at his home in Plains, Ga. around 3:45 p.m.

“My father was a hero, not only to me but to everyone who believes in peace, human rights, and unselfish love,” Carter said in a press release. “My brothers, sister, and I shared him with the rest of the world through these common beliefs. The world is our family because of the way he brought people together, and we thank you for honoring his memory by continuing to live these shared beliefs.”

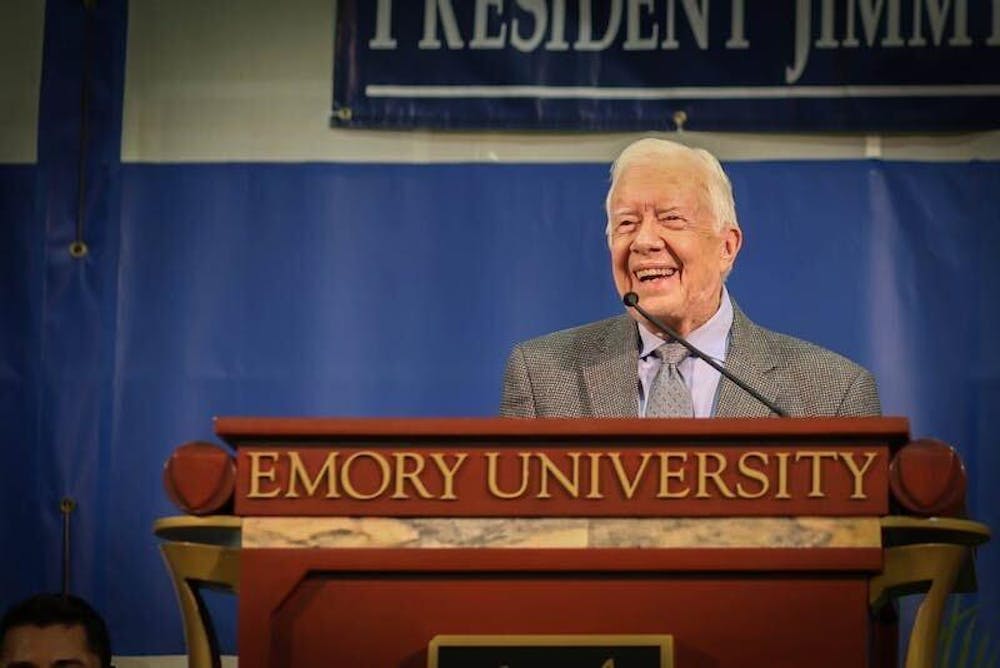

University President Gregory Fenves wrote in a message to the Emory community that Carter was a proud representative of the state of Georgia and highlighted his “deep connection” to the University.

“Today, Emory University has lost a remarkable friend and beloved professor—and the world has lost a beacon for peace, human rights, and justice,” Fenves wrote. “Across our community and the world, we are mourning the death of President Jimmy Carter and celebrating his remarkable life of 100 years.”

Carter’s health began deteriorating in recent years. Carter received surgery at Emory University Hospital in 2019 to relieve pressure on his brain from a subdural hematoma, caused by falls. Four years earlier, Carter was diagnosed with metastatic melanoma that spread to his liver and brain. He beat the cancer after receiving a novel treatment at the Winship Cancer Institute.

The Carter Center announced on Feb. 18, 2023 that the former president decided to forgo any further medical treatment and entered hospice care at his home in Plains.

The first president to not secure a second term in office since former U.S. President Hebert Hoover in 1932, Carter’s Oval Office legacy would ultimately be overshadowed by his prolific post-presidential career. Carter served a single term from 1977 to 1981, losing to former U.S. President Ronald Reagan in a historic electoral landslide in which Carter received just 9.1% of the electoral vote.

A year after leaving office, Carter and his wife, Rosalynn, founded the Carter Center in 1982, an Atlanta-based non-profit dedicated to bolstering democracy and human rights internationally, improving global health and fostering conflict resolution. During the Carter Center’s early days, Carter worked with two other staff members in an office on the 10th floor of the Robert W. Woodruff Library while the permanent building was still under construction.

He later received the Presidential Medal of Freedom in 1999 — which former U.S. President Bill Clinton bestowed upon him and his wife at the Carter Center — and won the Nobel Peace Prize in 2002 for his international humanitarian work.

Carter has been an esteemed figure at Emory since his first visit to campus in 1979 during his struggling reelection campaign, where he received an honorary doctor of laws degree at the Cannon Chapel groundbreaking ceremony. In a tradition dating back to 1982, the same year he left the presidency and joined Emory faculty as a university distinguished professor, Carter held student town halls, in which first-year students could ask the former president about anything — from contemporary political issues to his favorite type of peanut butter.

A progressive in the South

Born on Oct. 1, 1924 in the small farming town of Plains, Carter was the first president born in a hospital and the only president to return to his hometown permanently after leaving office, residing at his family’s peanut farm until his death.

With a population of about 611 in 1920, Plains is a rural town nestled in the southeast region of Georgia. The town’s population has remained relatively stable 100 years later, home to 573 people in 2020.

During a conversation with Creative Writing Professor of Practice Hank Klibanoff’s Georgia Civil Rights Cold Cases class in 2018, Carter told students that his mother believed in racial equality while his father “went according to the custom of those days,” insisting on segregation. Carter’s mother, Lillian, was a registered nurse and would frequently cross segregated neighborhood lines to care for Black families.

After graduating valedictorian of his class from Plains High School in 1941, Carter attended Georgia Southwestern State University for a year and the Georgia Institute of Technology for a year before graduating from the U.S. Naval Academy in 1946, the same year he married Rosalynn. Carter traveled the world as part of the navy’s early nuclear submarine program, but returned to run his family farm after his father’s death in 1953.

In the 2018 class visit, Carter said that his time in the naval academy transformed his views about segregation and race relations, showing him the value of treating others equally and the profound harm of discrimination. As a young child, Carter said he did not fully understand the implications of racial segregation, believing that Black children chose to attend different schools.

A devout Baptist, religion was an open and driving force in Carter’s life, deeply influencing his political career and humanitarian work. In his 2018 book “Faith: A Journey For All,” for which he won a Grammy in 2019 for Best Spoken Word Album, Carter presented his companionship with God as the basis for his responsibility to share love with others. Carter taught Bible classes throughout his career as a politician — including while in the White House — and after his presidency.

“I think that everyone should try to follow the tenets that are spelled out in all of the major religions,” Carter told the Wheel in a 2015 interview. “That is, a commitment to peace, to humility, to service of others, forgiveness, compassion for those who are suffering and love, which is the kind of love that Jesus demonstrated in his own life and teachings.”

Carter began building his political career after returning to his family farm, successfully running for a seat on the Sumter County Board of Education in 1955 and winning a Georgia State Senate seat in 1962. In the face of national calls for desegregation and the overturning of Jim Crow laws, Carter encountered significant pressure from his community to uphold the status quo. In 1958, his family farm was boycotted because he was the only white male in Plains to refuse to join the White Citizens Council, an organization that resisted desegregation.

However, during an early but important stage of Carter’s political career — a stage he regretted and shied away from speaking about in later years — he discovered that winning a Georgia election during the height of a conservative backlash to the Civil Rights Movement required racist appeals to white voters.

After losing the Democratic gubernatorial primary in 1966 to the avowed segregationist Lestor Maddox, Carter repositioned himself for the 1970 election by courting white voters uncomfortable with desegregation and sought the endorsement of prominent segregationists.

Although the conservative appeal was successful for winning him the governorship, Carter’s record while leading the state was largely progressive. His inaugural address drew national headlines when he forcefully called for the end of segregation, a stark contrast to the campaign he just ran.

“He's done what no other Georgia Governor has ever done,” Leroy Johnson, a prominent Black Georgia state senator, told The New York Times at the address. “He's attacked head on the question of racial discrimination. We are accustomed to hearing this kind of talk from white politicians behind closed doors before an election, not out in public after an election.”

In his short stint as governor, Carter sought progressive reform, increasing the number of African American people employed by the state’s government by 25% and cutting down on wasteful government bureaucracy.

A historic campaign and rocky presidency

Recognizing Americans’ distrust in establishment politics after the Watergate scandal, Carter, who had served a single term as governor, used his lack of national standing to his advantage. He ran in the 1976 presidential election as a political outsider disconnected with the corruption in Washington.

However, Carter’s name recognition was so low that when he declared his candidacy in 1974, the Atlanta Constitution ran a headline which read, “Jimmy Who Is Running For What!?” With nine other candidates in the Democratic primary, some of whom were well known on the national stage, many viewed Carter’s campaign as a long shot.

But Carter quickly learned how to navigate a newly-reformed Democratic primary, discovering that winning in early primary states would build momentum, attract media attention and generate donations and endorsements he could not solicit from the party. Carter catapulted to the top of a crowded field by focusing his campaign efforts on Iowa and New Hampshire — two early primary states where the Democratic National Committee’s new transparency reforms worked to his advantage.

“Carter’s impact on the shape and structure of the modern nomination system cannot be overstated,” political scientist Elaine Kamarck wrote in her authoritative book on primary elections, “Primary Politics.” “His two campaigns for the Democratic nomination taught subsequent generations of candidates the new rules of the road.”

After receiving the Democratic nomination, Carter beat Republican incumbent and former U.S. President Gerald Ford, winning nearly every state in the South and some electorally-important states in the North.

Carter’s presidential legacy was marked by a series of increasingly challenging domestic and international dilemmas that ultimately dropped his approval ratings and cost him a second term.

In perhaps the most consequential foreign policy action of his presidency, Carter facilitated the Camp David Accords between former Egyptian President Muhammad Anwar el-Sadat and former Israeli Prime Minister Menachem Begin in 1978. Both foreign leaders worked out a peace agreement that included the withdrawal of Israel from the Sinai peninsula, the opening of diplomatic relations between both nations and the establishment of U.S. monitoring posts. Carter was the first U.S. president to settle a dispute between two nations since former U.S. President Theordore Roosevelt in 1905.

Sadat and Begin were awarded the 1978 Nobel Peace Prize for the resulting deal, but Carter received little political attention at the time for his efforts.

As an early advocate for policies to fight climate change, Carter focused on achieving U.S. energy independence. He established the U.S. Department of Energy in 1977 and allocated more funding toward renewable energy programs, famously installing solar panels on the roof of the West Wing.

Carter’s successes, which often failed to receive broad or praiseworthy attention from the public, were squashed by a far-reaching oil shortage in the summer of 1979 and the Iranian hostage crisis in November of that year. Oil production from the Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries dropped dramatically as a result of instability in the Middle East, causing rising gas prices and long lines at gas stations across the country. At the onset of the Iranian revolution, Carter’s administration failed to rescue 52 American citizens and diplomats taken hostage at the U.S. Embassy.

The dueling crises at the end of his term made his reelection campaign nearly impossible. Carter lost the 1980 presidential election to Reagan in a landslide defeat, receiving only 49 of the 538 electoral college votes.

Post-presidential political involvement

In recent years, Carter frequently weighed in on the American political landscape, at times vehemently criticizing U.S. President-elect Donald Trump, and at others, taking a lighter tone compared to his Democratic peers. Carter made a brief video appearance at the 2020 Democratic National Convention where he endorsed current U.S. President Joe Biden to be the Democratic presidential nominee. Carter also endorsed Sen. Raphael Warnock (D-Ga.) in the 2020 special election.

Following the Jan. 6, 2021 U.S. Capitol insurrection, Carter denounced the attack as “a national tragedy” and said the riot “is not who we are as a nation.”

“Having observed elections in troubled democracies worldwide, I know that we the people can unite to walk back from this precipice to peacefully uphold the laws of our nation, and we must,” Carter wrote in a Jan. 6, 2021 statement.

Carter also discussed politics on Emory’s campus over the last few years. While answering student questions during his visit to Klibanoff’s class in 2018, Carter said he believed that U.S. Supreme Court Justice Brett Kavanaugh, who was accused of sexually assaulting Christine Blasey Ford while in high school, is “temperamentally unfit” to serve on the Supreme Court.

That same year, Carter wrote a letter to then-Georgia gubernatorial candidate Brian Kemp asking him to resign as Georgia secretary of state before the midterm elections, arguing that Kemp had a conflict of interest in overseeing an election for which he was also a candidate.

Town halls, a tradition of honesty

In one of the University’s longest-running traditions, Carter would welcome first-year students to campus with a town hall at the beginning of the fall semester. He began this event in 1982, and continued to speak at town halls through 2019. In 2020, the Carter Town Hall opened with a recorded video conversation between Carter and Jason Carter, while the 2021 and 2022 Carter Town Halls featured civil rights icon and former U.S. Ambassador to the United Nations Andrew Young and American professional soccer player and women’s rights advocate Megan Rapinoe, respectively.

Emory students remember a former president who never shied away from answering a question honestly, whether it be politically contentious or humorous.

At one town hall that received national attention, Carter broke a promise by publicly revealing his opinion of the 1998 Clinton-Lewinsky scandal in response to a student question, months after the disclosure of an affair between then-President Clinton and White House Intern Monica Lewinsky.

Carter said in September 1998 he was “deeply embarrassed” by Clinton's actions and by the political crisis that followed, also alleging that the president “had not been truthful” in a sworn deposition about the affair.

Prior to the town hall, Carter had remained silent about the scandal rocking the administration. He told students that before the town hall he promised Ford, a former presidential opponent whom he later grew friendly with, that he would not comment on the matter.

“I have to admit that this puts me in a difficult position,” Carter told the student. “Because, for the last 16 years, at town hall meetings and in classrooms, I’ve never failed to answer a question that a student has asked me, and I’ve never failed to answer it as truthfully and as completely as I could. … If it's not already in the newspapers, I will call President Ford and tell him I answered your question.”

Carter held his 20th town hall just three days after the Sept. 11, 2001 terrorist attacks on the World Trade Center. He called for national unity and to bring the terrorists to justice, noting that the overwhelming majority of Muslims “are as deeply committed to peace and justice as I am.”

Many student questions over the years took a personal tone, allowing Carter to reflect on his political career, give advice or weigh in on debates over the trendiest condiments.

At a town hall in 2018, he was asked if he preferred crunchy or smooth peanut butter. “For sandwiches, I prefer creamy peanut butter,” Carter said to applause from the crowd. “And for munching during the day on a cracker or something like that, I prefer crunchy.” When asked in 2019 what his thoughts are on almond butter, Carter bluntly replied, “I haven’t tasted it, and I don’t intend to.”

One student asked at the same town hall if Carter could recount the most important day of his career.

“The most memorable day of my career, of my life, was when my wife said she would marry me,” he replied.

Carter is preceded in death by Rosalynn, his wife of 77 years. She died on Nov. 19, 2023, and Carter attended her memorial service at Emory University’s Glenn Memorial United Methodist Church on Nov. 28, 2023. He is survived by their children Amy, Jack, Donnel and James, 11 grandchildren and 14 great-grandchildren.

Jack Rutherford (he/him) (27C) is a managing editor at The Emory Wheel. He is from Louisville, Ky., majoring in economics on the pre-law track. When not working for the Wheel, he can normally be found rowing with Emory Crew, where he serves as president, or at an Atlanta Opera performance. In his free time, Rutherford enjoys listening to music and walking in Lullwater.