The first article I ever wrote for the Emory Wheel’s queer column was about Georgia O’Keeffe, the iconic modernist painter who forever transformed American art with her exploration of color, scale, ambiguity and abstraction. For those unfamiliar with her name, you will likely recognize her famous flower paintings; she created about 200 large, vibrant, carefully composed artworks depicting detailed sections of a myriad of flowers throughout her life.

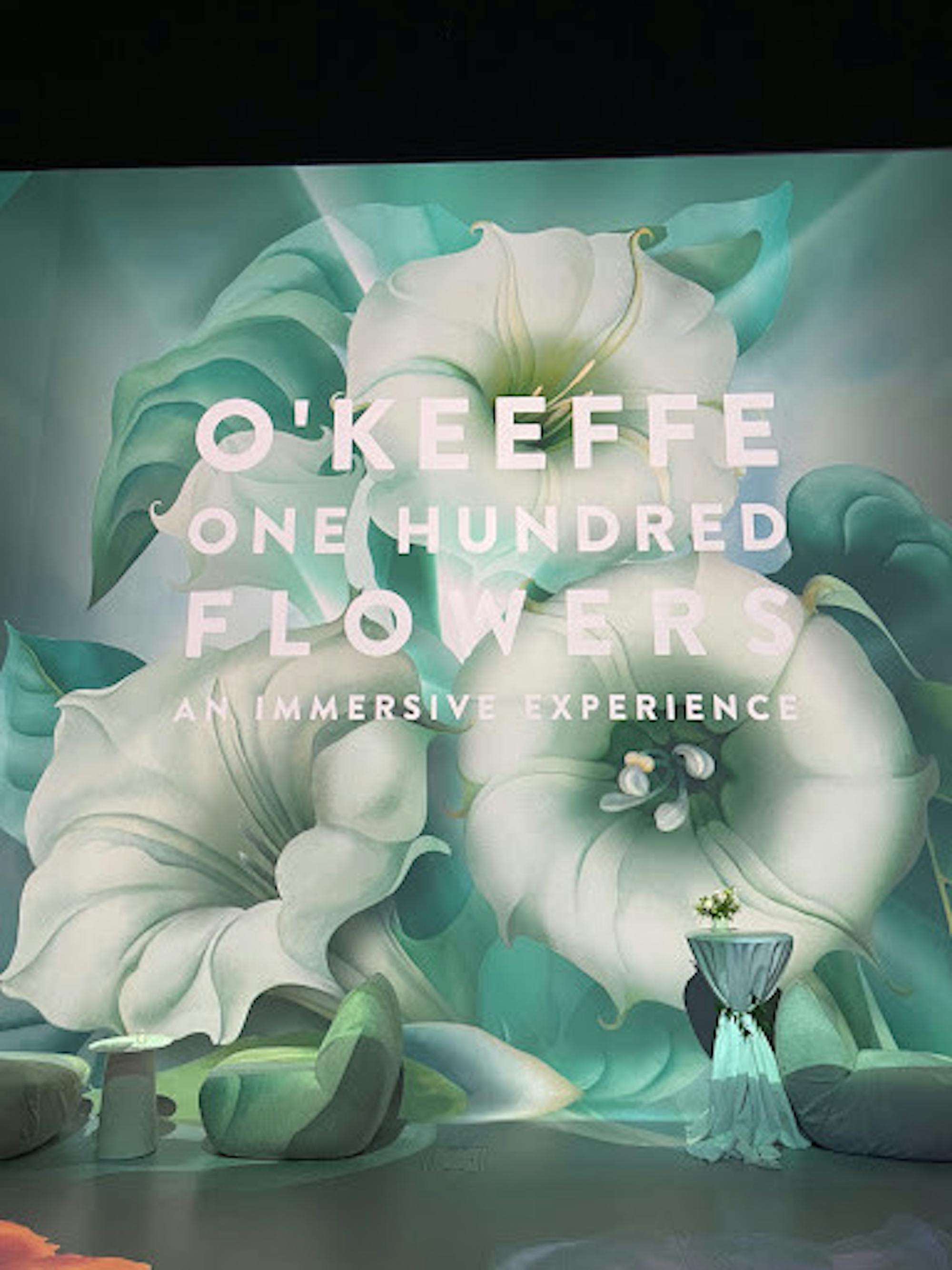

O’Keeffe’s flower renderings, and many of her other artworks, have been described by the exhibition organizers as “reshaping” the ways in which we see nature and the world around us. The recent Illuminarium exhibition, “Georgia O’Keeffe: One Hundred Flowers,” can be described as reshaping the ways we see O’Keeffe’s artworks. While one could see this reframing of O’Keefe’s art as both positive and negative — I still cannot decide which way I feel — it can certainly be described as innovative and very “of our time.”

This Illuminarium exhibition is an “immersive experience,” a new style of artistically curated space that has taken the world by storm. This particular experience featured a virtual moving collage of projected flowers from O’Keeffe’s artworks gliding along the walls of two rooms. The curated artworks are based on the book “Georgia O’Keeffe: One Hundred Flowers,” published in 1987 by Nicholas Callaway, who attended the opening event for the show. His best-selling book features the works of a female artist and its success indicates both how talented O’Keeffe is and how prohibitive the art world is to women, particularly women of color.

Upon entering the world of “O’Keeffe: One Hundred Flowers,” swaths of color, light, sound and smell immediately meet your senses. As O’Keeffe’s flowers move and dance across the contours of the room, patrons snap photos, grab drinks at the bar and chat loudly with their friends. The room smells like the vague suggestion of a daffodil, and the vibrant colors of O’Keeffe’s petals, leaves and filaments do their best to distract you from the industrial piping and neon green exit signs that dot the previously-drab space.

Immersive experiences have recently been made fashionable in the American mainstream, whether about Vincent van Gogh, Claude Monet or Gustav Klimt. These experiences are scalable, moveable, Instagram-able and, frankly, commercial. As Anna Weiner of the New Yorker so perfectly described, “What we were paying for was proximity—not to the paintings themselves, but to the idea of them.” The paintings are broken up into fragments of brushstrokes and colors, making it easier to commodify them as glorified moving wallpaper. It makes me question how much these artist-based immersive experiences are more a reflection of ourselves and less a reflection of the artist.

When standing inside these immersive experiences, it is difficult to contend with the expensive tickets and ultimately inaccessible art world, without feeling like a pawn of capitalism, drawn in by pretty flowers and then used for profit.

While, yes, I may have felt used for profit as I watched this expensive display of what should be free, publicly-accessible art, I did enjoy the artistic interpretation. As my Jewish mother always tells me: it is fine to hold two opposing thoughts at once! There is something that these immersive experiences, especially of such abstracted yet recognizable artworks like O’Keeffe’s, are capable of achieving for the visitor. These are multisensory and, quite literally, multidimensional experiences. “O’Keeffe: One Hundred Flowers” goes so far as to pump flower scents into the rooms and serve flower-themed drinks and food at the opening. Additionally, they played an all-female soundtrack and use LIDAR technology to make the flowers on the floor move with your steps. There were flowers everywhere you turned.

Clearly, new generations of consumers are sick of static museum spaces, as museum attendance is decreasing year after year. These immersive experiences offer something new, exciting and idiosyncratic. As Callaway believes, these shows are the future of how people want to consume art. There is a certain magic of perceived luxury as the pulsing, colorful walls and floors rotate around your feet, curating all of your senses as the perfumed air wafts the aroma of an iris under your nose. While these experiences don’t necessarily allow you to perceive an O’Keeffe artwork for what the artwork alone is, the show serves as a beautiful, reinterpreted, moving collage of her artworks.

Artistic, immersive experiences have also often been lauded for prompting visitors to go beyond passive observation, making them feel as though they can live and breathe within and around artworks. In that sense, I appreciate how these experiential formats de-center the stuffy, silent, “white box” style of modern Westernized museums. This concept of the sanitized museum, with blank, homogenous white walls and glass boxes, emerged in the 1930s and has been incredibly problematic since, they evoke elite, emotionless artistic spaces, creating barriers for non-white visitors and stifling certain artistic voices. If these immersive experiences are the correct first step to challenging those inaccessible spaces, then I applaud them.

As I sat eating my tulip-shaped tomato hours d’œurve, an iconic O’Keeffe quote flashed across the screen. “I’ll paint what I see – what the flower is to me… but I'll paint it big and they will be surprised into taking time to look at it.” This immersive experience, like O’Keeffe’s own paintings, will undoubtedly surprise you into taking the time to look. Once you start to truly look, it is nearly impossible not to talk, question and engage. While O’Keeffe may not have loved the capitalist endeavor that these immersive experiences are, I can imagine she would have enjoyed the debates and conversations about the future of art and consumption that arise.