We rarely value the artistic merit of functional objects. However, respecting both the function and the beauty of an object begets a deeper understanding of that object, artistic or otherwise.

Many ancient civilizations, including the Incan people who lived in the southern highlands of Peru, recognized the beauty in functionality. Ceremonial and aesthetic objects would often mirror the shapes and materials of everyday functional objects: the paccha, for example, was a ritual watering device used in ancient Peru to initiate the agricultural cycle of maize growth. A nearly 580-year-old paccha is currently on display at Emory’s Michael C. Carlos Museum, and it should be praised for its intricate technique and brilliantly symbolic depiction of the critical maize cycle.

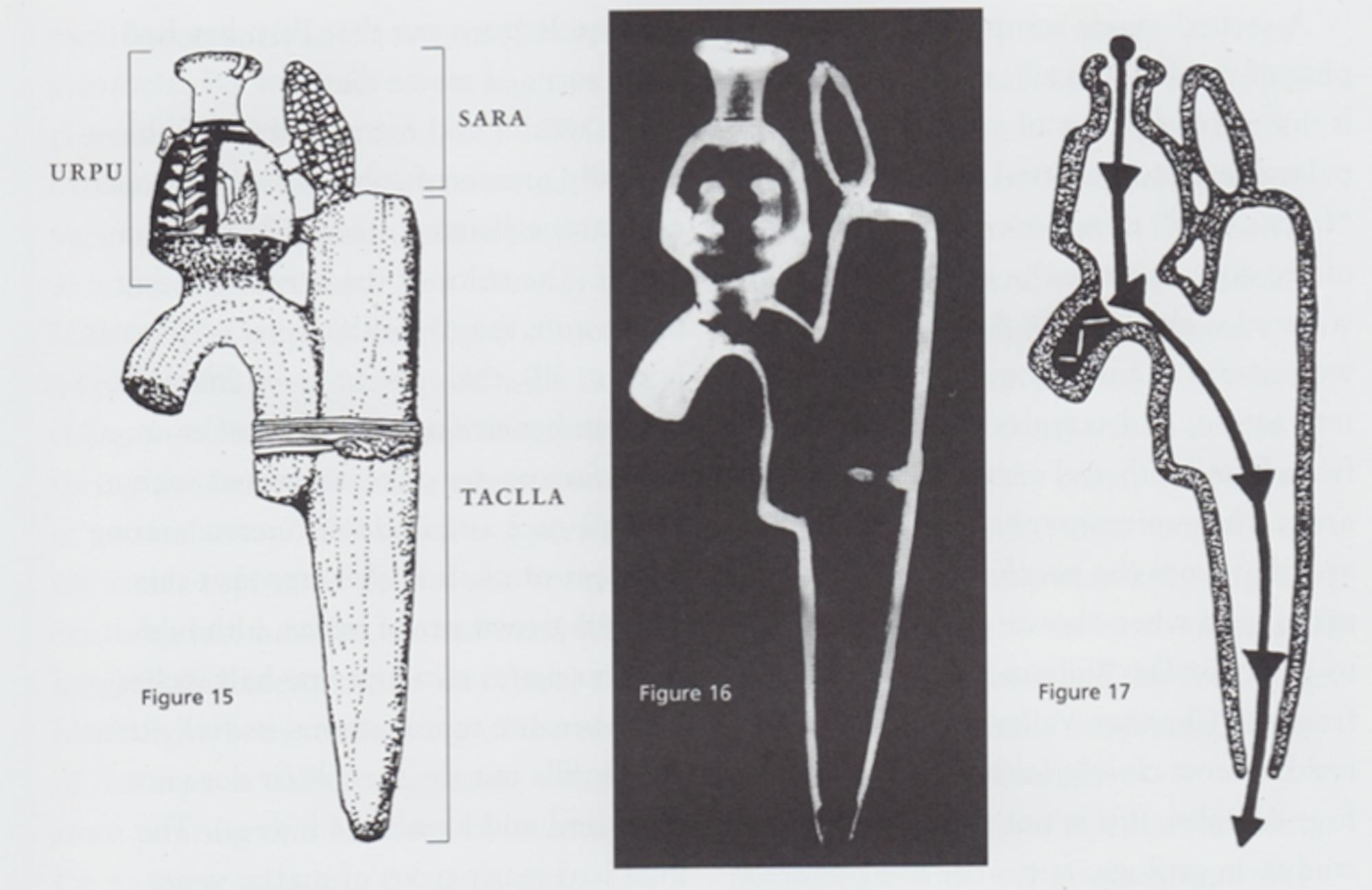

The long, brown ceramic body of the paccha resembles the shape of a taclla, the foot plow used by the Incas to plant maize. The golden vessel at the top of the paccha is an urpu, a common Incan container used to store maize and brew chicha, a form of maize beer. The top of this ceremonial object is crowned with a small ear of very naturalistic corn painted in black slip, representing the final harvest of the corn crops. By placing the maize storage container and the maize itself atop the maize planting tool the Inca exemplify their advanced and elaborate storytelling skills, highlighting the cycle of maize and making what could be a functional foot plow into a powerful ritual object.

The paccha relies upon sophisticated symbolism — it showcases the shapes of everyday agricultural tools to aid the growing and harvesting of maize. Though not lifesize, the paccha depicts the details of a taclla foot plow, an urpu used to hold maize drink and an ear of corn.

As Peri Klemm (02G) noted in her thesis, specialists at Emory worked to uncover the use of this object by examining the residue left in the bottom hole of the paccha. The tip was quite worn and discolored as compared to the rest of the sculpture, and they found traces of chicha, a fermented maize drink, in the bottom hole as well as sand particles from the Chancay area of coastal Peru, an area conquered by the Inca. The paccha was a ritual watering device for the Earth; the Incas would thrust it into the soil they had just conquered, allowing the dirt to “drink” from the watering of chicha into the ground as the agricultural year began. While the soil was generally watered with traditional irrigation, this first drink of water for the new soil was seen as a way to honor the Earth through a gift and ensure that maize would grow successfully. It’s simply miraculous how something as small as grains of sand and discoloration can reveal the entire purpose and intention behind such a beautiful ritual.

The paccha celebrates the beauty of functional everyday objects and the role of each of those tools in the maize-growing cycle, a cycle critical to the Incan empire. When considering the popular art of today and the canon of art history, ritual objects that mirror everyday function are often overlooked. A modern appreciation of such cycles and ritual, especially through art, can enrich our connection to the Earth and our fellow humans like the Incan people. The paccha is a work of art — it deserves the same level of time in the spotlight and praise as a Rembrandt or Andy Warhol for its use of symbolism and exemplary artistic skill.

The infusion of exigency and symbolism, while not often seen in contemporary artwork, is a valuable and critical characteristic of exquisite and impressive Inca artworks like this paccha.

This article is part of an ongoing column on underrated and unsung visual artwork. Read the other articles here.