This Saturday, Sept. 14, Jews around the world will gather in synagogues for Yom Kippur, a day of fasting and judgement. Despite the solemnity of the season, somehow I feel like this year I do not have as much to atone for as usual. Don’t get me wrong: there’s still plenty of wrong I’ve done this year for which I must make amends. But relatively speaking, this year feels markedly light.

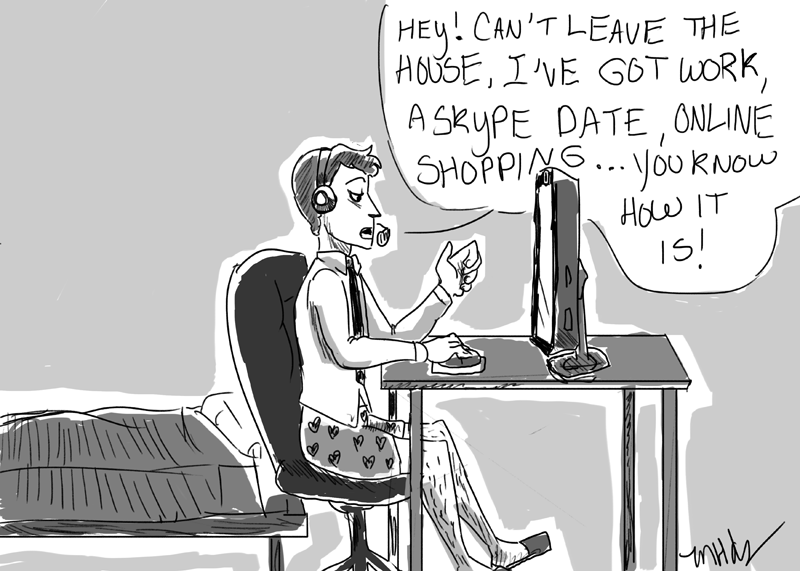

Maybe it’s my aging brain, unable to recall things from more than a few months ago. But maybe it’s not just me. I can’t quite put my finger on it, and maybe it’s already cliché to ascribe all phenomena to it these days, but I can’t help but feel that technology has something to do with it. To put it simply, having spent the overwhelming majority of the past year looking at some screen – usually a computer, smart phone, television or a simultaneous combination of all three – I cannot help but feel that I have not really done all that much. When I reflect on the year that has passed, I am struck by how much time I spent online reading (articles, blogs, tweets, status updates, etc.), watching movies and television and corresponding with others via an endless number of platforms. The internet is for, well, lots of things; but unless absorbing information is somehow wrong, I am not sure all those hours spent online were altogether transgressive.

Perhaps the area of my greatest virtual malfeasance was the covetous feelings I sometimes had when scrolling through my social network news feed – Facebook, for example, has the tendency to make others’ lives seem so fabulous. I’m guilty there. But surely, regret over hours spent scrolling through videos of cats or lists of graduate student quirks cannot be the basis for the spiritual renewal that is called for on Yom Kippur.

If I’ve done little online for which I must repent this year, I’ve also done less wrong than usual this year “in real life.” Again, I cannot attribute this to anything positive I did consciously. I was simply too busy in my virtual world (sometimes worlds) to venture out into the real world and commit those wrongs to which we all fall prey, like being a bad friend or telling a white lie. (On the latter, perhaps technology has been a boon: although researchers have found that lying in an email comes easier than face-to-face lying, others have hypothesized that email lying rates are lower because people know that the record of their statements is preserved.)

There is much yet for researchers to explain about the relationship between technology and religion. To date, technology has raised important and largely unforeseen questions for traditional religious practice, the best known issues being bioethics and so-called “cyber-rituals.” But what I am describing seems less direct, and yet, more all-encompassing. Technological innovations have changed our daily routines, and thus, looking back on the year that was, I feel as if the usual benchmarks will simply not do. During this season of holy days, I am forced – like others, I imagine – to ask if my newfound virtual life has been a worthy one. The weights of the scale are encoded, as it were, with ones and zeros, and I cannot make heads or tails of them.

One fleeting feeling gives me hope. It is the possibility and promise of strong re-engagement with the world in which I have worked, over many years, to figure out good from bad. Maybe this year, I need to atone for not doing enough good rather than not doing that much bad. Guilt by neglect, if you want to call it that, for having spent so much time in virtual worlds of my making. This year, I repent for sins of omission rather than commission.

Jason Schulman is a graduate student in the History Department.

Cartoon by Mariana Hernandez

The Emory Wheel was founded in 1919 and is currently the only independent, student-run newspaper of Emory University. The Wheel publishes weekly on Wednesdays during the academic year, except during University holidays and scheduled publication intermissions.

The Wheel is financially and editorially independent from the University. All of its content is generated by the Wheel’s more than 100 student staff members and contributing writers, and its printing costs are covered by profits from self-generated advertising sales.