Emory University’s first Chancellor and tenth President Warren A. Candler made it known that he believed women were not fit to be medical or law students at the 1919 Commencement.

Men and women sitting side by side during anatomy lectures or hunched over the same dissection experiment would create an “indelicate and injurious situation,” he said. Female lawyers would “not promote justice in the courts,” so allowing them into the law school would be a waste.

However, in March 1953, former University President Goodrich C. White announced that the Emory College of Arts and Sciences and the School of Business Administration were going to admit women starting fall 1953, making the entire University coeducational.

Yet, women had already been attending Emory for years, despite Candler’s earlier grievances. More than 1,500 women received degrees from the University before it was officially coed, as reported in an April 1953 issue of Emory Magazine, formerly known as the Emory Alumnus. Hundreds of other women attended the University without graduating.

“It was a hodgepodge,” Assistant Director and University Archivist John Bence said. “You sort of had to advocate for yourself, you had to convince an administrator. So there were multiple ways in, but the official policy sort of created that resistance as well.”

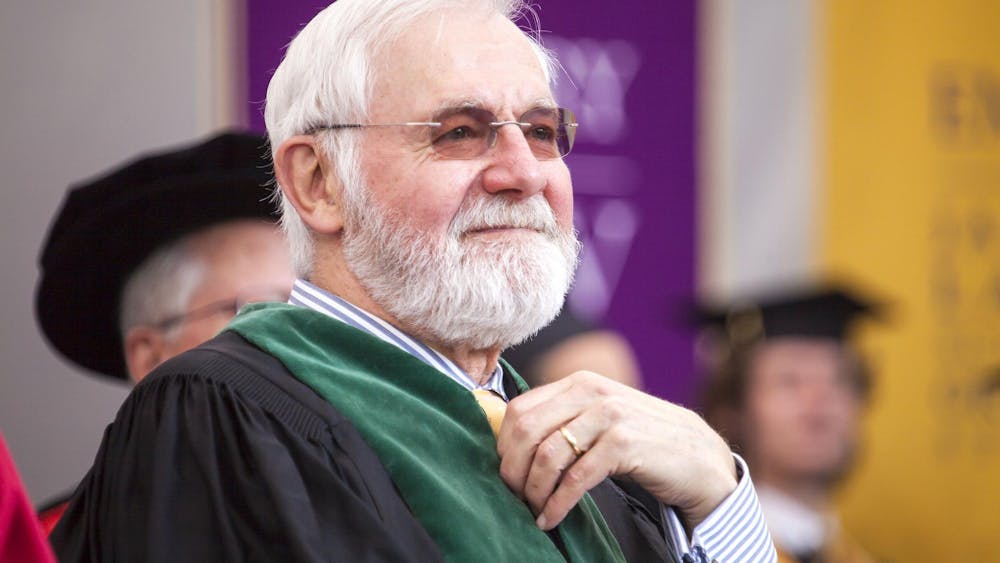

Women’s resistance to a male-dominated Emory was successful, Bence said. Out of the 4,282 students enrolled at the University in the year before the College and the School of Business became coed, 1,095 — more than a quarter — were women, University Historian Emeritus Gary Hauk wrote in a March 25 email to the Wheel. That number included students from the nursing, graduate and library schools, which were all coed prior to 1953.

Several women were also in majority-male schools, such as the medical school, law school or the College — but these women had to fight their way in, Bence explained.

Before 1953

While male students gathered in the dining hall to eat their lunches together, women like Sarah Watson Emery (33C) ate her peanut butter sandwich alone.

Emery ate in a small lounge on the second floor of the library every afternoon. The room — which only had one window overlooking the quadrangle — and its adjoining bathroom were the only places on campus dedicated to women, and Emery did not feel like she could eat her lunch elsewhere, according to an October 1989 issue of Emory Magazine.

“Even if I had the money, I never would have ventured into the cafeteria which the University ran for male students,” Emery said. “None of the women students ever went there, to my knowledge.”

While Emery attended the college before it went coed, the history of women at Emory began 69 years earlier when Mary Haygood Ardis (1888ex), the daughter of former University President Atticus G. Haygood, was permitted to take classes at Emory in 1884. She later transferred to Wesleyan College (Ga.), an all-women's school, to complete her degree. Ardis is now considered an 1888 graduate, Bence explained, because students who spend a few years at Emory are still listed as alumni with the “ex” code in directories.

The 1953 issue of Emory Magazine states that N.S. McIntosh, who is believed to have been a close relative of a professor, was also listed as a student at the time, but she did not graduate.

Although it is believed a few female relatives attended the University in the following years, women did not officially graduate from the University until Eleonore Raoul (1920L), who enrolled at the School of Law in 1917. Raoul’s historic attendance was a special case. According to Bence, she quickly enrolled the day Candler was out of town, a move that was vital to her education, as Candler was starkly anti-coeducation.

Her graduation in 1920, which was the first for women at Emory, created a path for other women to follow, despite the limit on female enrollment at the time. Cecilia B. Branham (1920G) received her master’s degree the same year from the newly established Graduate School.

The Candler School of Theology began accepting women in 1922 to “prepare them for Christian service in home and foreign mission fields,” the Emory Magazine reported in 1989. The Wesley Memorial Hospital, where many female students trained as nurses, relocated to the Emory campus in 1922, and the Library School of the Carnegie Library of Atlanta did the same in 1930. The Library School awarded women with degrees before the move, and previous female graduates were given retroactive membership into the Emory Alumni Association.

In May 1926, the Emory Magazine reported that former University Registrar J. Gordon Stipe announced that a limited number of “mature” women were eligible to attend the College of Liberal Arts to study education — a largely female-dominated field — following “insistent demands from the schools and teachers of the entire South.”

Ultimately, Bence said, most of the women who graduated before the official coed decision studied subjects typically seen as “women’s work,” such as nursing and teaching.

“As they opened professional training programs, and then as those sort of became part of Emory, they were certainly from the beginning conceived of as admitting women,” Bence said.

The surge of women attending Emory ended in 1938, when the University signed a contract with Agnes Scott College (Ga.), an all-women’s school, agreeing to no longer accept female undergraduates and instead registering them through Agnes Scott, Bence added. The women could take courses at Emory if they were not offered at Agnes Scott. The contract ended in 1952, according to the 1989 issue of Emory Magazine.

By 1953, only three women graduated from the business school, while about 40 women graduated from the dentistry and law schools. Only 17 women were permitted to attend the medical school, the first of whom was W. Elizabeth Gambrell (31G, 46M, 49MR), who was admitted in 1943. Just 200-300 women graduated from the College.

The women also faced unequal facilities on campus, Bence said. Most female students were from the Atlanta area, as Emory did not offer female housing. Female students were also all white, and it stayed that way until Verdelle Bellamy (63N) and Allie Saxon (63N) — both of whom were Black — graduated from the nursing school in 1963.

“Most of them were middle class white women who had time and resources,” Bence said.

The different avenues for female graduates creates a confusing history, and the 1953 issue of Emory Magazine reports that even Stipe was often “uncertain what the current policy was.”

Once women fought their way onto campus, however, Bence said that they were met with no female clubs or dorms, except for Harris Hall, which housed nursing students. The female college experience mimicked a job — most seemed to come to campus, attend class and then immediately leave.

Female students also experienced sexism on campus. The 1989 issue of Emory Magazine states that a faculty member told Emery not to apply for an English scholarship to pursue a master’s degree because women don’t “have professional academic careers. They just get married and have babies.”

After 1953

The decision to make Emory coed was partially made out of necessity, Bence said. Student enrollment at Emory plummeted as men were drafted or volunteered for military service after the United States entered the Korean War in 1950. Tuition had to be raised just to meet the University’s budget.

“As a result, they were sort of like, 'Oh, there's this dip happening, and we need more money,’” Bence said. “‘So why would we refuse people who are willing to pay and are qualified?’”

White’s decision to admit women was also influenced by the new Faculty Dean Ernest C. Colwell, who wanted to promote the humanities departments and figured women would be more likely to study the humanities than men, Bence added.

But the University’s decision to go coed did not translate to housing. An article announcing Emory’s decision to move coed in the March 26, 1953 issue of the Wheel quotes White, who said “We do not plan to build any new dormitories, add any new courses or change our educational structure because of this decision.”

Even with the lack of housing on campus, University administration was worried about women living off campus unsupervised, Bence said. He explained that a woman from Arlington, Va. wanted to attend Emory and rent out an apartment, but the administrators would not allow her to enroll because they were “so nervous” about her not living with her parents or in a dorm.

“That just shows you the strength of the sexual politics at the time about women's autonomy and paternalism,” Bence said.

The lack of housing affected women until 1958, when three dormitories were built. Sororities were established on campus the next year, following sorority alumni from other institutions reaching out to former Dean of Students E. Hebert Rece. The 1989 issue of Emory Magazine reports that Rece once wrote he was being “educated rapidly and painfully” about having female students.

“They are all over the place and in everybody’s hair now,” Rece wrote. “We are facing the question of sororities or no sororities. We keep trying to put it off, but it keeps pressing in on us.”

However, even after they received their own lodging, female students needed their parents to sign a permission card for “the late-leave privileges,” indicating that they were aware of and approved the hours their daughters might leave their dorms without supervision, according to the 1989 issue of Emory Magazine. Male students did not have to do the same.

The University also lacked women’s locker rooms, so they had to change into gym clothes in their dorms and wear long coats to walk to the physical education building. Women’s facilities were not built until almost 25 years later.

The 1989 issue of Emory Magazine noted that male students generally saw the decision to admit women as “favorable,” while few were far more “enthusiastic.”

“I think it’s absolutely wonderful,” Clyde Wilkes (56C, 58D) said. “I’ll go hog wild. I think it’s the greatest thing in the world — WOMEN!”

However, some men were reported to be dreading the arrival of their female classmates.

“It will have a definite debilitating effect on the intellectual standard of achievement,” Wallace C. Clopton (53G) said.

However, the women proved Clopton wrong. Almost 25% of the female students had B averages or higher, while the women as a whole had a B-minus average, which was “considerably above all-school and all-male marks.”

Mary Brooke DeLoache (55C), who transferred from Vanderbilt University (Tenn.) to become one of the first women to attend Emory after it went coed, told Emory Magazine she was motivated by professors’ and male students’ doubt.

“One of the things we did was make all A’s the first two semesters and prove them wrong,” DeLoache said.

Sexism was common on campus, and it was reflected in some 1953 University publications. The November 1953 issue of Emory Magazine described a female student’s appearance in detail, saying “her features, figure and charm make her a standout in any company. … Complexion: perfect.” The student, who also was also featured in a seven-page photo layout, was engaged, and the editors wrote that “Satan tempted” them to keep her wedding a secret, but they had “horrible dreams of unknowing young bachelor alumni in distant places quitting their jobs and rushing back to Atlanta to pay court.”

Bence noted that women in the 1950s were also given a book called “Dooley’s Rib” — an allusion to Adam’s rib, which Eve is said to have formed from — that told them what to pack and outlined the rules of the dorms.

“It’s just so alien to us today,” Bence said. “That’s a real time capsule.”

Most clubs also selected a girl to claim as their own, giving them titles such as “SGA Girl” and “Wheel Girl,” Bence explained. The clubs then hosted beauty pageants.

However, both DeLoache and Mary Welch McConaughey (56C) told Emory Magazine they found the University to be small and homey, fostering the “golden age” of their lives. DeLoache was elected senior class president and McConaughey performed in the women’s chorale. They ate lunch in the dining hall with other women instead of being isolated in one room.

“Emory was where I developed, where I found out what I wanted to be and who I was,” McConaughey said.

Madi Olivier (she/her) (25C) is from Highland Village, Texas, and is majoring in psychology and minoring in rhetoric, writing and information design. Outside of the Wheel, she is involved in psychology research, the Emory Brain Exercise Initiative and the Trevor Project. In her free time, you can find her trying not to fall while bouldering and obsessively listening to Hozier with her cat.