Theater Emory’s “We Are Proud to Present a Story About the Herero of Namibia, Formerly Known as Southwest Africa, From the German Sudwestafrika, Between the Years 1884-1914” is set on a platform stage in the middle of the room, with a table of bottles and boxes beside the stage. The play’s six characters march onto the stage in unison, facing the audience. An actress clears her throat, and we are thrown into an introduction to the play, one to which the other five characters quickly protest. Still, our narrator (Jeanette Illidge), who dubs herself Black Woman, and the five others with similar monikers, launch us into a PowerPoint presentation about the history of Namibia — specifically, its history under colonial rule.

The play was written in 2012 by New-York based playwright Jackie Sibblies Drury. It tells the story of six actors attempting to put on a play about the German genocide of the Herero people, as documented by a German soldier in letters to his wife. Directed by Emory faculty member Eric J. Little, the production took place on Oct. 25 and 26 in the Mary Gray Munroe Theater, and will be showing on October 31 and Nov. 10 and 11. The play is dynamic and candid, brought to life by vivid direction and acting, and resonates with current issues.

The characters, caricatures of their race and gender, comply with the canon of the letters to varying degrees. Some believe that they must follow what the letters read. Others work off-script. This raises the one of many tensions of the play: can the genocide of the Herero be portrayed truly, and accurately, by a white man? The German soldier does not detail the crimes he commits against the Herero people in his letters to his wife, but his letters remain the only accessible written document of German presence in Namibia.

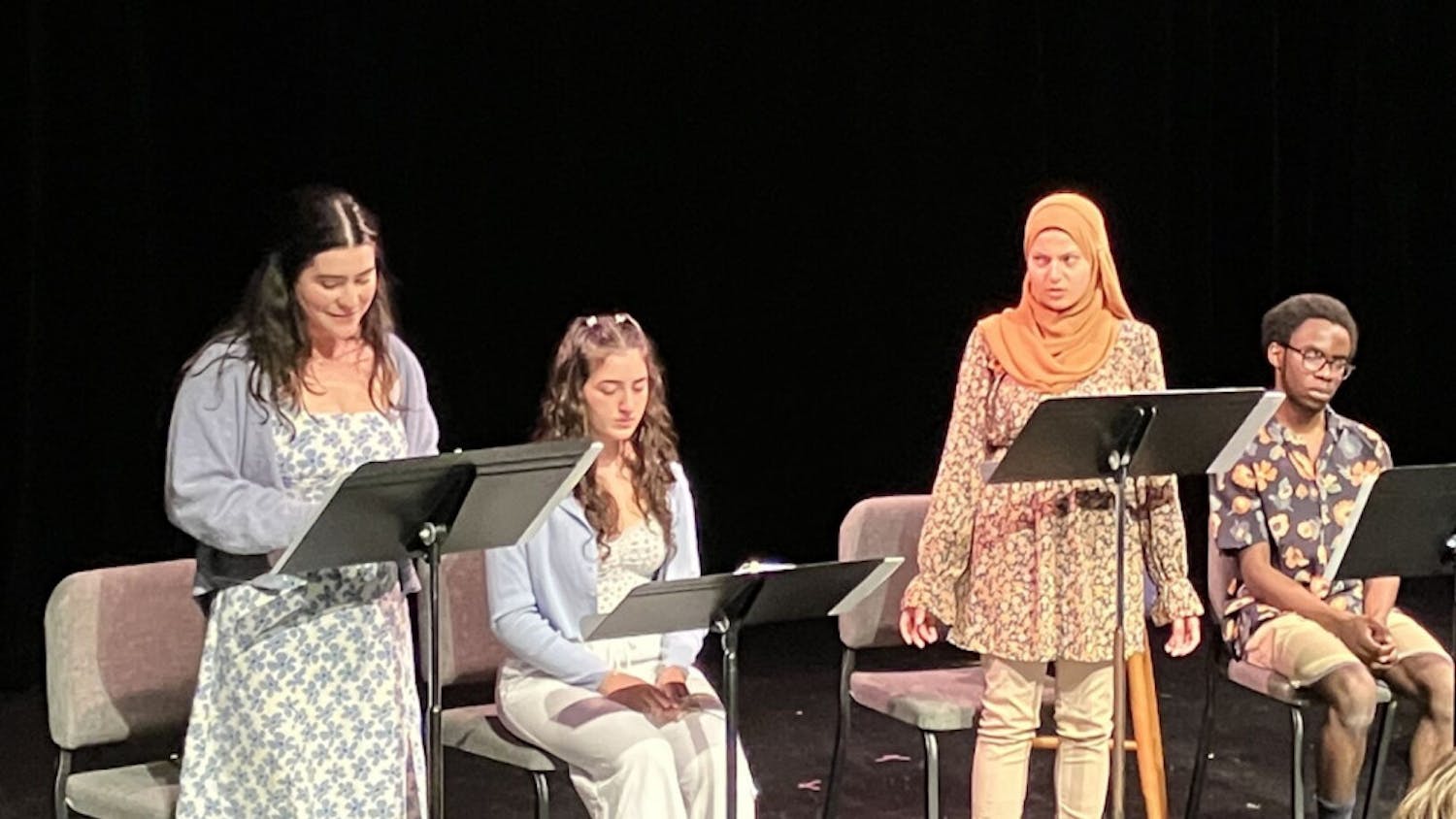

Though the characters’ play is seemingly hindered by those diametrically-opposed views, the story does not unfold in such easily-defined lines. White Man (Colin Sphar) and Another White Man (Peter Buzzerio, 21C) vye for the leading role, while the white woman, Sarah (Sophia LiBrandi, 22C) pursues her own spotlight. Black Man (Ashton Carter) demands that they tell the story of Africa, not a narration of soldier’s letters. While Another Black Man (Randy Boyd) agrees, his views are limited by his own ignorance. Black Woman stands between the five of them, desperate to find compromise. Their perspectives diverge and conflict, but their motivation is singular: they seek to portray the story as best they can.

The story of “We Are Proud to Present” is captured beautifully. The minimalist stage — fitting for a play rehearsal — lends a canvas to the rich auditory and visual direction. Little ingrains a sense of musicality throughout the entire play, whether it’s in haunting drum-beats and chants, or in one of the few outright musical numbers, which includes Drake’s “In My Feelings.” The actors make use of the whole space of the theater but always leave the stage feeling balanced, providing a sense of continuity throughout the play. The lights wash the stage in stark contrasts, between light and dark, vibrant color and none.

The play-within-the-play ultimately progresses to modern conflicts, with scenes that are unapologetic in their subject matter, and even less so in their presentation. Mentions of the Holocaust give the viewer reference to the scale of the tragedy and we are reminded that the loss of Herero lives is of equal gravity. As the play-within-the-play strays from the German soldier’s letters and Namibian genocide, we are led through the Jim Crow era to modern day. One moment echoes the shooting of Trayvon Martin, which had occurred while Drury wrote the play, as Little explained after the show. Another scene boasts language similar to that expressed by people who wanted confederate statues to remain, again rehashing the debate about the best way to preserve history.

The scenes are violent, emotionally and physically, and exhausting for both viewers and actors. The characters face their own prejudices, and in doing so force the audience to consider their own, too. It is easy to turn away from such a challenge, but impossible to look away from this play. The play’s actors slowly lose the ability to differentiate reality from fiction, a change most notable in Black Man. The violence is not contained within the play-within-the-play; the characters are victims of it in real life, afraid of others and themselves. Their attempt to progress, and society’s, feels futile. The virulent racism in Namibia resonates through history — both within and outside of Drury’s script.

The weight of the storyline could only be carried by strong actors, and those willing to delve into their own psyche. Carter rises to the challenges of Black Man’s role brilliantly. LiBrandi captures both the comedy and resolve of her character, Sarah. Boyd’s Another Black Man is charismatic and memorable. The play is demanding on all parts, for its characters, actors and audience, but the experience rewards those who accept the challenge, granting them an unflinching look at racism, history and the intersection between the two.