“Gatecrashers: The Rise of the Self-Taught Artist in America,” on view at the High Museum of Art, is a beautiful and earnest portrayal of America — its pain, its beauty, its wrongs, its comforts, its hope and its downfalls. Through their unique narratives and individual hurdles, which mirror what many see in the United States already, the exhibition’s featured self-taught artists represent a cultural history that is distinct, complex and emotional.

The collection of artists displayed in this exhibition were vastly more diverse in race, class, gender, style and lived experience than I had seen in a special exhibition before, standing in stark contrast to the popular Calder-Picasso exhibit housed just a few floors above. Featured artists John Kane, Horace Pippin and Anna Mary Robertson “Grandma” Moses each experienced barriers to art training and were self-taught, rising to popularity in the first wave of mainstream interest in self-taught art. That ascension in artistic popularity occurred in the U.S. between 1927 and 1950, a time during which the public sought original art separate from European tradition that represented the character and cultural history of this vast country. The exhibition followed the trajectory of these artists over time, inspired by the first groundbreaking exhibitions of self-taught artists at MoMA in 1938, 1939 and 1942.

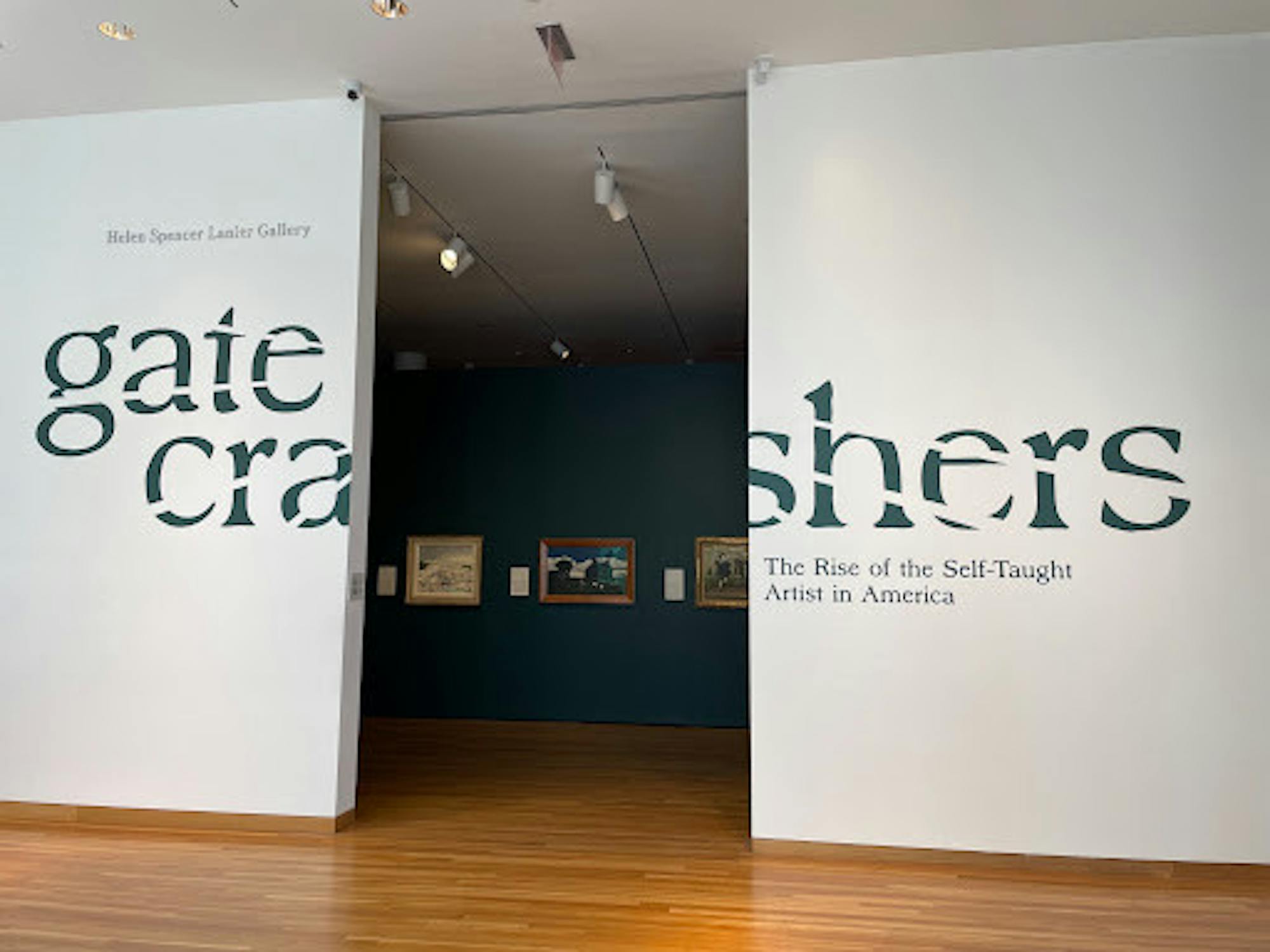

While Kane, Pippin and Moses may have been the three most prominent names in the world of self-taught artists from the U.S., the curators clearly did not want to turn this exhibition into a narrow look at their lives and oeuvres. Instead, the curators also celebrated the lesser-known self-taught artists of that same period, including Josephine Joy, Morris Hirshfield and Pedro López Cérvantez, situating these artists in conversation with one another. The dynamic between the more popular and the lesser-known artists, as well as their varied artistic techniques and biographies, brought the exhibit to life. Despite featuring over 60 works in a small gallery space, I felt as if the exhibition passed in the blink of an eye. The gallery design allowed this exhibition to flow smoothly, with an eye-catching first entrance leading into winding galleries painted in deep, viridescent earth tones.

Both the artworks themselves and the historical context provided by the labels and wall text enrich the viewer’s experience, especially as you learn of the “firsts” accomplished by many of these artists breaking down barriers in the elitist world of high art. Each canvas was more than a pretty sight; they were a collection of histories, narratives and, quite frankly, victories. A prime example of this is Joy, the first female painter to have a solo exhibition at MoMA, despite not being classically trained.

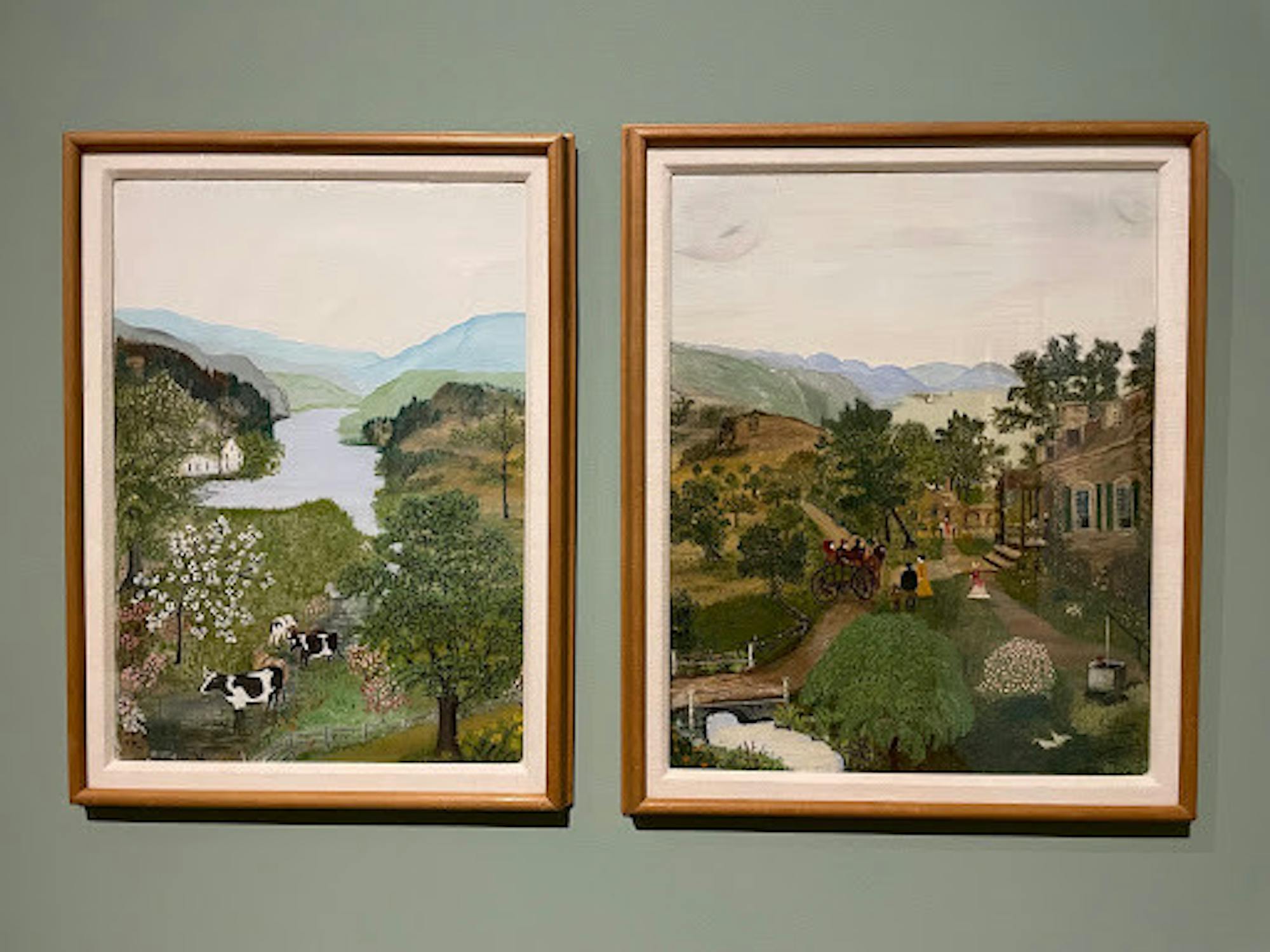

These featured artists were so defined by their outside employment that their first exhibition catalogues used their trades, not their art, to identify them. “Grandma” Moses was identified as “farm wife,” as she tended to her many children and worked on her farmland while creating detailed, unique artworks. While her artworks appear simple from a distance, they are comfortingly detailed up close. There is a nostalgia imbued into her work, even if you have never known the places or the people she portrays. Moses’ depiction of rural American life was unusual for the high art scene of her time, and many were struck by the tranquility and naïve style of her work. Her landscapes are dreamy, yet her artistic practice is quite raw and real.

While the exhibition did celebrate these quotidien portrayals of the peaceful countryside, the curators were clearly not ignorant about the hostilities toward self-taught artists and artists of color in the U.S. The artworks of Pippin, the first Black man to be the subject of a monograph, added significant nuance to this narrative of the U.S. Pippin had fought in the all-Black 369th Infantry Regiment in World War I, and after suffering a gunshot wound to the arm, he used art to help his rehabilitation, creating artworks with a wood-burning technique that recalled the branding of enslaved people in the U.S. Artworks like “The Whipping” stood alongside the tranquil countrysides of Moses, the smooth New Mexican landscapes of López-Cervántez and the plaid-wearing men of Kane, impelling visitors to not just accept a singular perspective on the history of the U.S.

Not only were the sundry artworks quite intentionally tied together by the curators, but the entire exhibition was repeatedly linked to the work of contemporary self-taught artists in the High Museum collection at large. Placards labeled “Collection Connection” were featured along the way, explaining how current self-taught artists have used means similar to those in early 20th century U.S. These labels inspired me to explore the rich “Self-Taught and Folk Art” gallery on the top floor of the museum as well.

Everything from gallery design to label writing and artist representation was considered with great intentionality, helping educate the viewer and place the more than 60 artworks in their context. Without using the heft of “big name” artists or famous subject matter, “Gatecrashers: The Rise of the Self-Taught Artist in America,” closing December 11th, is a success and one of my favorite exhibition experiences at the High this year.

![IMG_0064[31].jpeg](https://snworksceo.imgix.net/whl/bd1509fc-0fff-41c3-8a17-14169776d877.sized-1000x1000.jpg?ar=16%3A9&w=500&dpr=2&fit=crop&crop=faces)