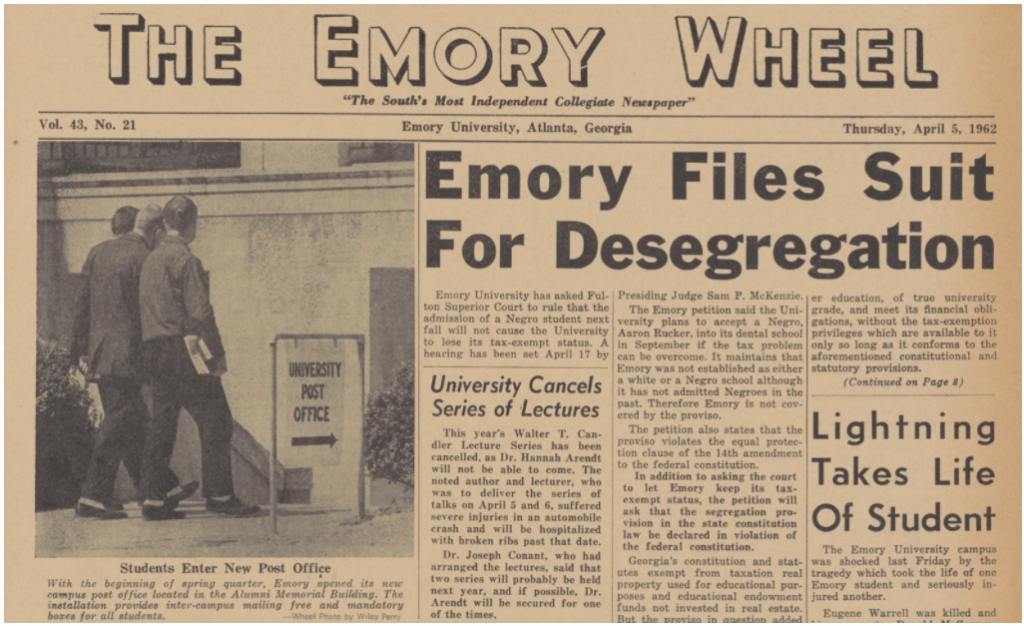

April 5, 1962. The Wheel reports that Emory has sued to permit its integration. Courtesy of the Rose Library.

Content warning: This article references and includes images of the Ku Klux Klan and past articles containing racial slurs.

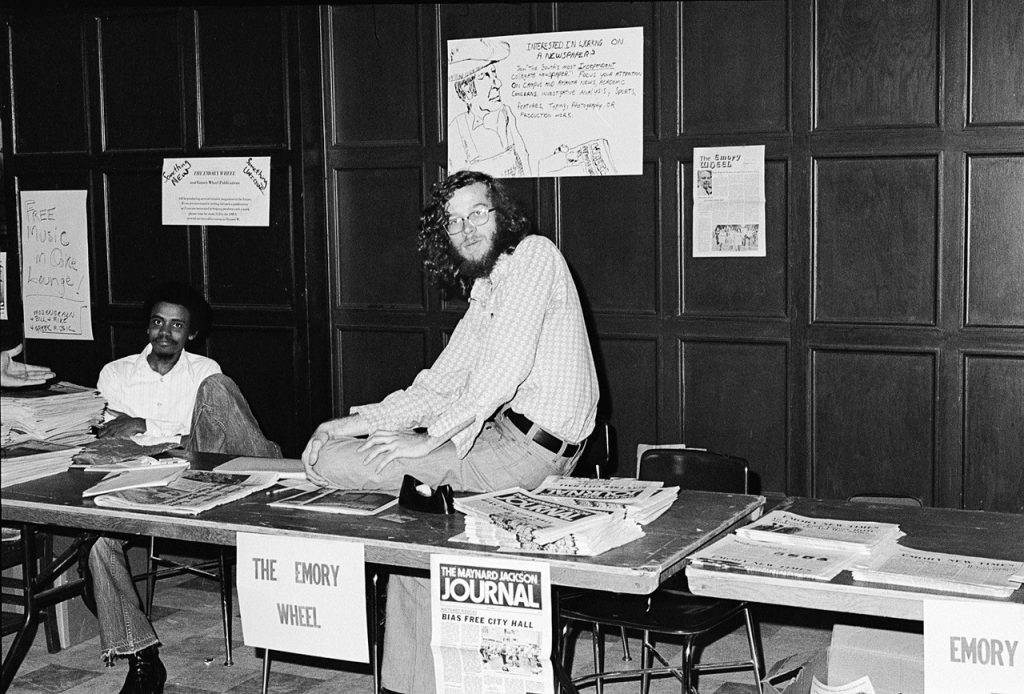

In 1973, two students sat at a table during Emory’s student activities fair, pictured below. One, sitting atop the Wheel’s booth and piercing the camera is white student Geoff Gay (74C), who was editor-in-chief. The other is a Black student whose name remains lost in Wheel history.

Many former editors whom we contacted for this piece couldn’t place his name; former Photo Editor Richard Sexton (75C) only referred to him as a ”really sweet guy.” Everyone seemed to remember that there was one Black writer, but no one could give him the humanity of a name. Where Gay sat in the center of the frame, literally and figuratively dominating the Wheel’s presence at the fair, the Black student reclines off to the side, a minor player in the photo and, in all likelihood, the Wheel itself.

Fall 1973. Former Editor-in-Chief Geoff Gay (74C) and unknown writer. Courtesy of the Rose Library.

This photo is nearly 50 years old, but it nevertheless evokes the current state of Emory student journalism. Just as the Wheel provoked the formation of a competing, more conservative paper in the 1970s, so it did just last year. Just as the Wheel marginalized Black, Indigenous and people of color (BIPOC) then, so it does today. Throughout our investigation for this piece, we have sought buried truths from throughout the organization’s history in hopes of sparking not just a conversation about the problems they reveal, but also action — real, sustained action that will change future generations for the better.

While many stories, such as Emory filing a suit for desegregation, made front-page news, many more slipped beneath the waves of history. In this piece, we investigated The Wheel’s coverage, culture and DEI efforts since 1963. We found that, for decades, BIPOC have been silenced and their stories have been ignored. Before our words are diminished as mere anger, we must ask ourselves, what are the uses of anger? In memory of civil rights advocate Audre Lorde’s revolutionary work, “My response to racism is anger. That anger has eaten clefts into my living only when it remained unspoken, useless to anyone.”

Coverage

In the late 1960s, the Wheel took some significant steps toward becoming a more inclusive organization. As early as 1968, a group of Black students authored demands to the University through the Wheel. The Black Voice, a column featuring Black students’ opinions, first appeared in 1975, according to then Editor-in-Chief Brenda Mooney (76C). For the moment, hate speech began to ebb. As early as 1969, the Rev. Dr. Otis Turner (69T, 74G) became one of the first Black students, if not the first, to write regularly for the Wheel. Yes, the Wheel improved during Emory’s integration, but its minimal steps toward inclusion still masked rampant prejudice. For an overwhelmingly white paper that routinely published the N-word, desegregation was only just beginning.

Content warning: Below are images of the Ku Klux Klan (KKK).

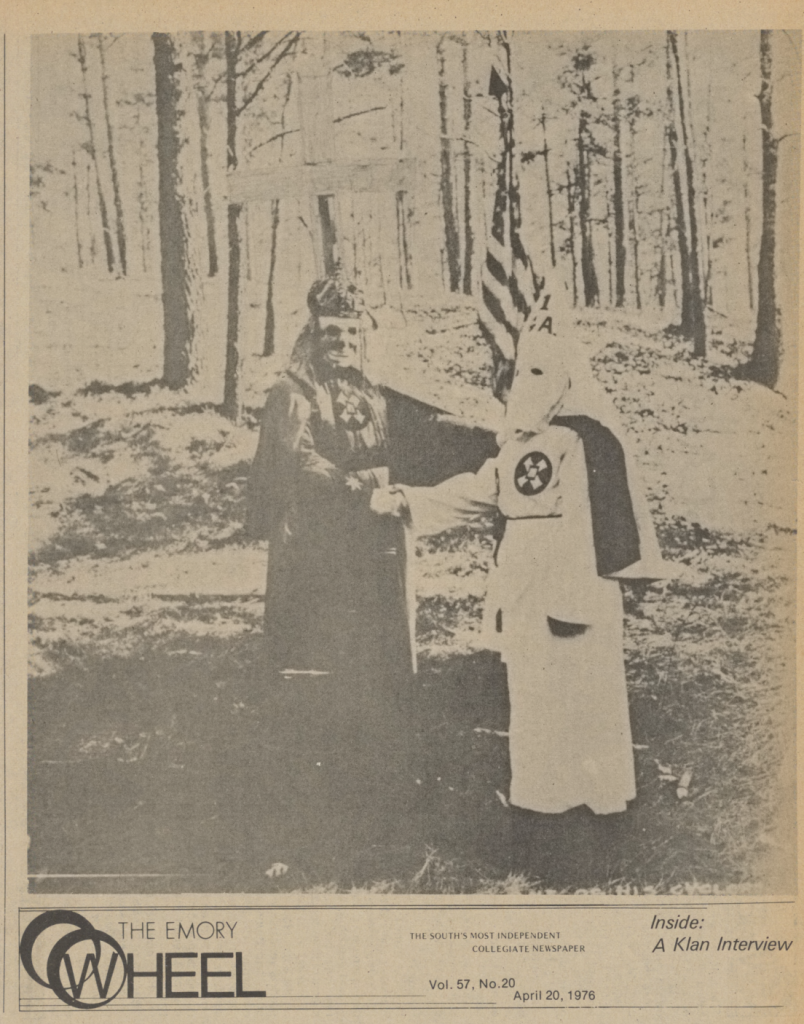

April 20,1976. The Wheel publishes Sverdlik’s interview with a member of the Ku Klux Klan. Courtesy of the Rose Library.

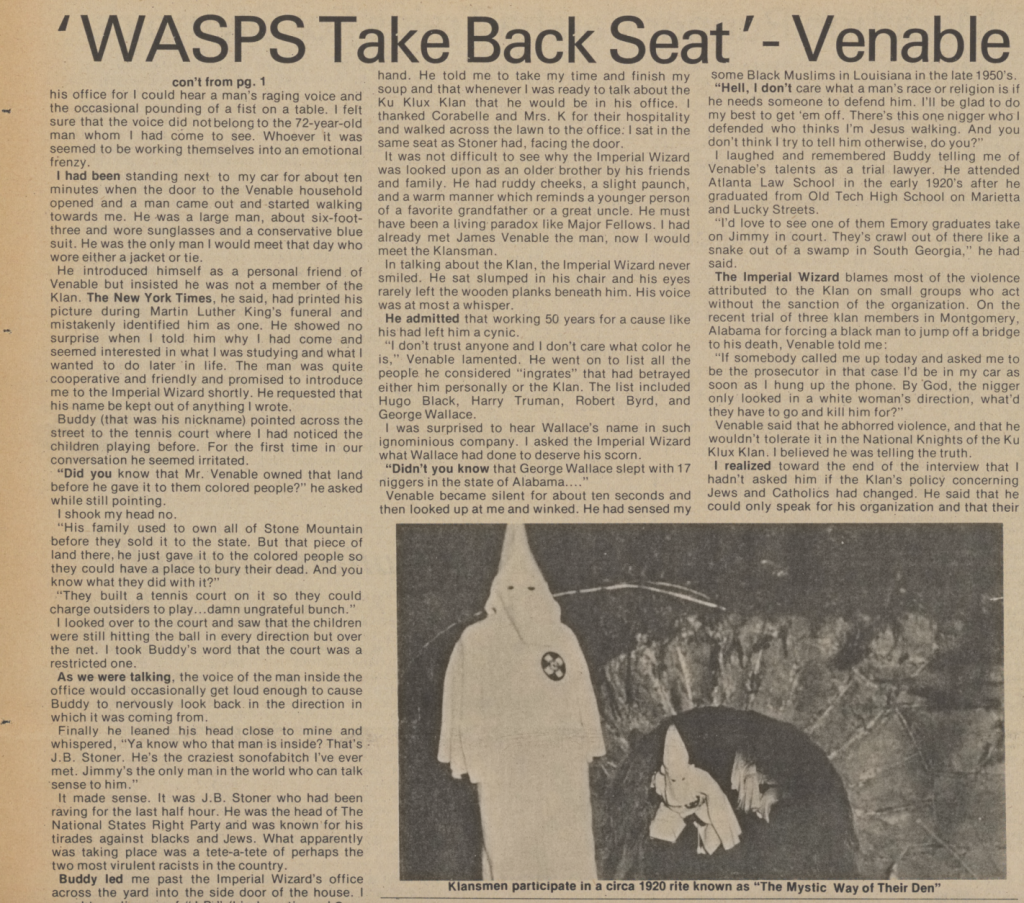

April 20, 1976. The Wheel publishes an image of Ku Klux Klan members with the American flag. Courtesy of the Rose Library.

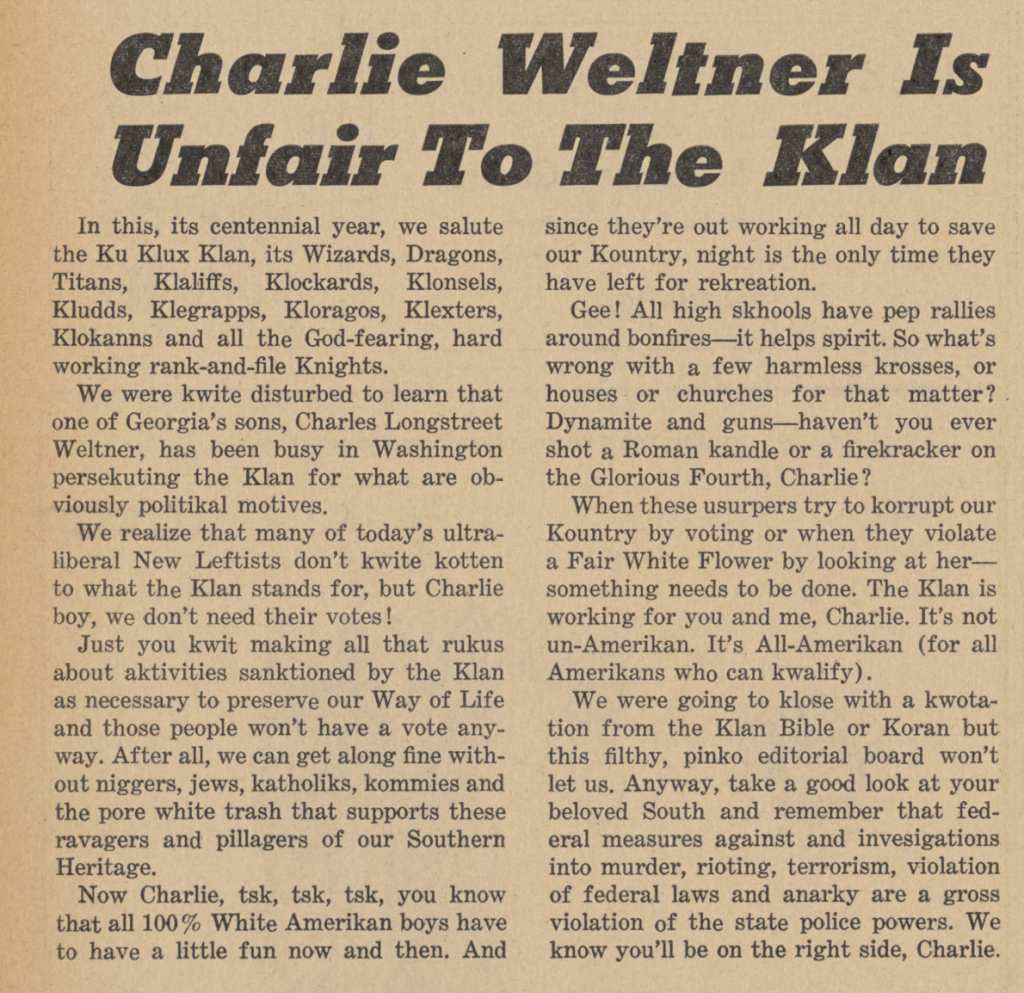

March 3, 1966. An unsigned satire article written from the perspective of the KKK appears in the Wheel. Courtesy of the Rose Library.

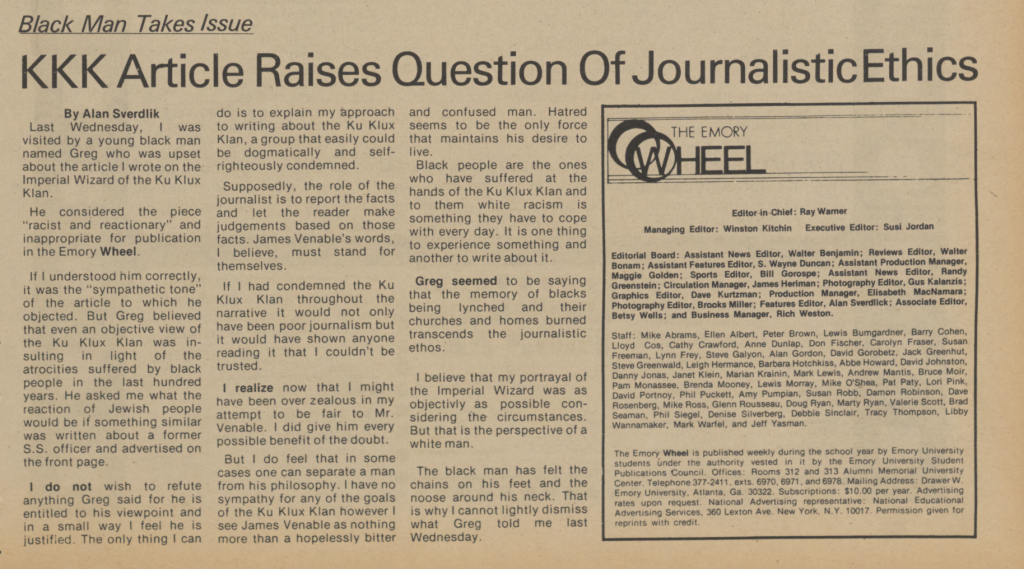

April 27, 1976. Sverdlik’s response to a Black student, Greg, who criticized his article. Courtesy of the Rose Library.

That veneer of inclusion was grossly disrupted by the continuous publication of hateful ideas following Emory’s official integration, which occurred in 1963. In 1976, Features Editor Alan Sverdlik (77C) published a feature on the oldest living member of the Ku Klux Klan. A week later, he wrote an equivocal article responding to a Black student, referred to only as Greg, who argued that both the “sympathetic tone” of Sverdlik’s article and its publication constituted blatant misconduct by the Wheel. Greg was right. Sverdlik’s article was clearly neglectful in both giving a platform to a Ku Klux Klan member and failing to acknowledge the lasting harm of doing so. Even worse than Sverdlik’s detached response to Greg, however, was the fact that Wheel editors had published that piece in the same issue as several articles amplifying Black students’ voices. Among them were articles concerning the Emory Black Student Alliance’s demands for change, the establishment of the first predominantly black fraternity, the ideas of Betty X (Malcom X’s widow) on Black power and Black first-years criticizing Emory’s isolating culture. This was not the first time Wheel editors published members of the Ku Klux Klan in the form of op-eds or interviews, nor would it be the last.

In addition to spotlighting white nationalism, the Wheel also produced sexist, photographic coverage of women, especially Black women. In one especially heinous tradition, editors in the 1960s and 1970s chose a weekly “Wheel Girl” to feature, including an overtly sexualized photo and a short, reductive biography of a female student each week. While only about 10 Black students attended Emory in 1967, three Black women became Wheel Girls from 1968 to early 1969. Though such depictions may appear inclusive, they’re really just tokenizing. The Wheel objectified Black women at alarming rates, a visual representation of the Wheel’s racist values.

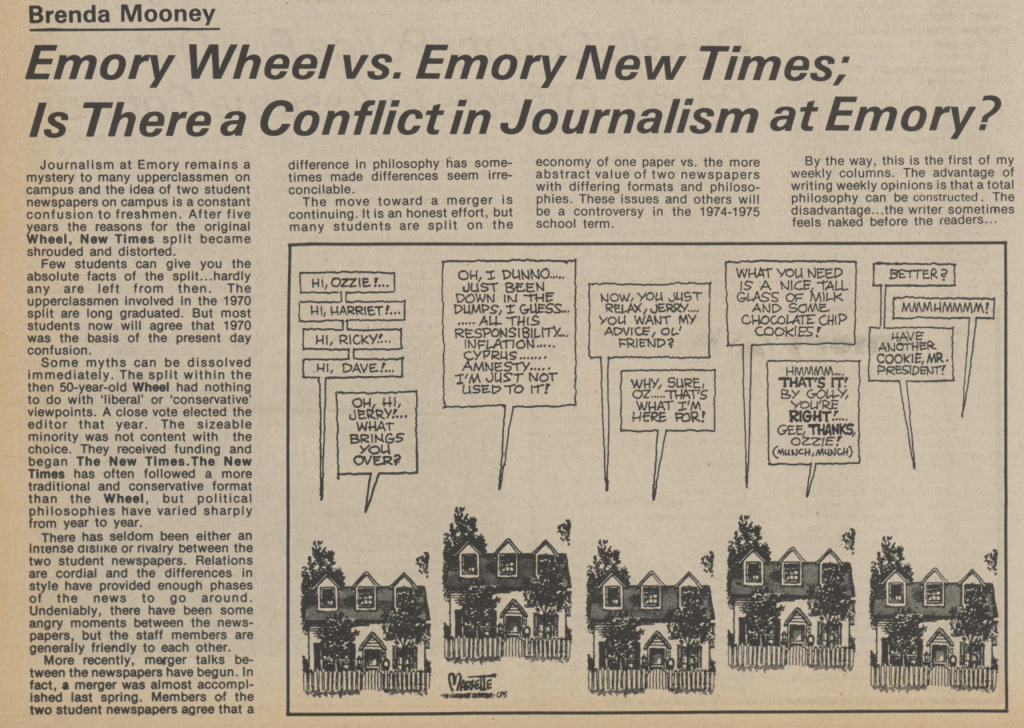

Still, the Wheel’s publication of anti-war articles, discussion of sex-positive issues and celebration of a few Black writers still earned it a strongly progressive reputation in the 1960s and 1970s. According to several former Wheel editors, a second student newspaper known as the Emory New Times split from the Wheel in 1969 in response to the paper’s progressivism.

While the leaders of both papers claimed their differences centered on journalistic practices, the reality appears much different. Sexton, for example, explained that New Times editors “thought [Wheel staff] were a bunch of hippie wackos, left-wing communists who were not of the frame of mind that they were.” Five years after the split, the two papers finally agreed to merge in the fall of 1974. Mooney, who ran for editor-in-chief against a former New Times editor, described her campaign as a “race between the ideologies.” In reality, both organizations simply justified their hateful speech in the name of free speech. As such, conflating the Wheel’s left-leaning reputation and its failure to disavow hatred, however, would be a disservice to the communities it harmed.

The story of the New Times and the Wheel may be decades old, but it should sound very familiar — just last year, another group of conservative staff left the Wheel because of ideological differences and formed a new organization, the Emory Whig. After a few right-wing opinion writers concluded that the Wheel had unjustly suppressed their ideas, they decided to create a new organization for themselves in the name of exercising their freedom of speech. Yes, the Wheel rejected their articles on rare occasions, but it almost always did so with justification. One current Whig writer once submitted a draft that, among other things, used racialized language to malign prominent Black Americans and insinuated that systemic racism did not exist. That is not the exercise of free speech. It’s hatred.

And BIPOC are always expected by white-dominated societies to face the hatred they receive. As Lorde wrote in “Uses of Anger,” “Oppressed peoples are always being asked to stretch a little more, to bridge the gap between blindness and humanity.”

Sep. 24, 1974. Mooney argues that the Wheel-New Times split did not concern ideology. Courtesy of the Rose Library.

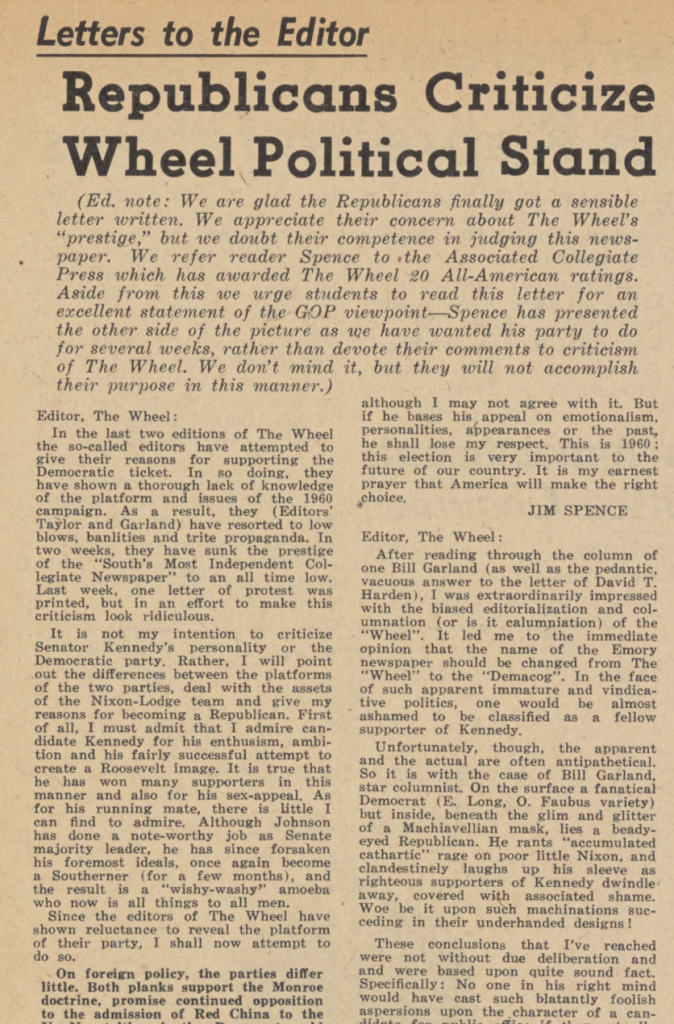

Oct. 27, 1960. Republicans criticize the Wheel’s progressivism in letters to the editor. Courtesy of the Rose Library.

So where do we draw the line between hate speech and promoting free discourse? As current and former editors, we have had to make tough decisions about the articles, ideas and writers we platform. It isn’t always so cut and dry. Often, we must contend with the costs of publishing an article, either to our own identities or to those of others, and weigh them against the social benefits of showing to the world the ideas within. The line between hate speech and protected speech is often obfuscated by coded references to journalistic ethics and standards of objectivity.

Content warning: The below image contains racial slurs.

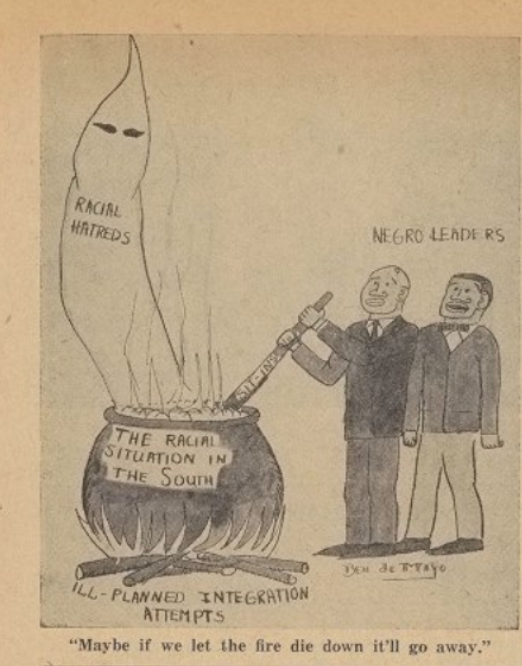

Nov. 10, 1960. A Wheel cartoon attacks integration efforts in the U.S. South. Courtesy of the Rose Library.

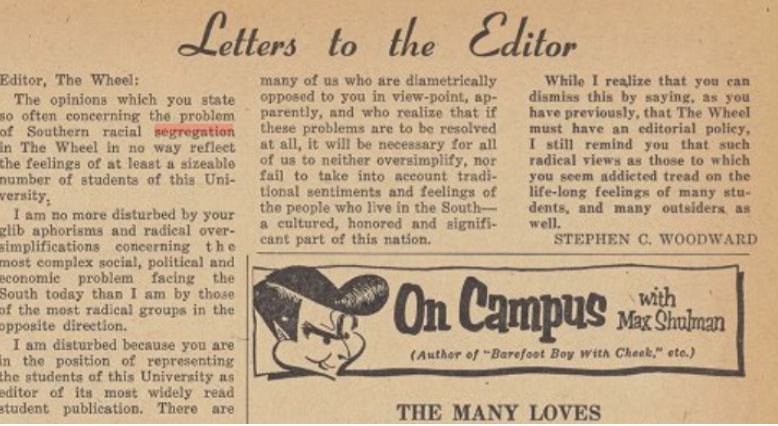

1956. Stephen C. Woodward (56C, 59M, 62MR) condemns the Wheel’s support of desegregation in a letter to the editor. Courtesy of the Rose Library.

For instance, when editors received cartoons like the one above, which vilifies Black civil rights leaders, they had to evaluate the tradeoffs of publication. To these editors, free speech outweighed the costs of publishing a glaringly racist cartoon and effectively trivializing integration. Many similar tradeoffs also risked alienating and harming BIPOC and continue to do so. On the other hand, when deciding to publish pieces supporting the end of “separate but equal” policies, the Wheel was branded as radical and extremist by people like the editors of the New Times. We still face such dilemmas daily. As editors, we have both the power and responsibility to balance practicing ethical journalism with honoring the freedoms of expression and speech. And evidently, the Wheel will always be subject to criticism on either side of the debate. However, we must choose to be on the right side of history.

Both at Emory and throughout the world, the press is powerful. Just last year, the willingness of Newsmax, One America News Network, Fox News and others to feature and even condone false claims of voter fraud and calls for violence led to a riot at the Capitol. We may not have the reach of those organizations, but our ethical mandate is the same. As journalists, we are defenders of human rights.

“But it was a different time”

For many former editors and writers whom we interviewed, especially those from the 1960s and 1970s, historical relativism was an easy way out of the hard truth. Racial justice might be more comprehensible in hindsight, but what was unethical decades ago remains unethical today. In other words, the desegregation-era Wheel existed in another time, but it did not exist under another moral standard. The only real difference was the extent to which white people failed to notice that dissonance.

The “different time” argument not only rings morally hollow, but it also erases the work of those few who did oppose the prevailing winds of apathy and prejudice. People like former Editor-in-Chief Rodney Derrick (69C), who worked for the Black Panther Party, became a member of the Black Workers Congress and organized fellow white students to march with mistreated Black high school students, deserves laud, not minimization by default. Turner, who was also the first Black student admitted to the Candler School of Theology, was a pioneer; he was responsible for some of the first Black-authored columns in the Wheel’s history. Activists like Turner and Derrick did their part for history, and we should not forget the meaning of their work.

To suggest that racism of the last 70 years was merely a by-product of its time would be to dehumanize and invalidate the lived experiences of BIPOC in the face of desegregation.

Culture

If we look only at the extent to which BIPOC students are represented within the Wheel’s staff, the last five decades appear transformative – while the paper was almost entirely white for decades after Emory’s integration, nearly half of current Wheel editors are BIPOC. But those gains are neither evenly distributed nor as encouraging as they initially seem. Most non-white editors at the Wheel are Asian American, as have been many recent editors-in-chief. For other minority groups, representation has remained the same. Other BIPOC, such as Latinx and Indigenous students, have little to no representation at the Wheel. The Wheel had one Black editor in the 1960s, and that lack of representation remained true for most of the century. As Amos N. Jones (00C) noted, “I was the only non-white person for a long time on the Wheel.” Boris Niyonzima, one of the founding Black members of the Wheel’s Editorial Board, recalled in his own op-ed the glaring whiteness of the Wheel: “I am the only black person and often the only person of color. That is a daily ritual.”

Today, still, the Wheel only has one Black editor. In some ways, our growth as an organization has been tantamount to naught. This lack of growth was even reported by our University’s former president James Wagner in 2008, when recounting that whiteness accounted for the Wheel’s failure to cover the presidential inauguration of Barack Obama. Wagner and his task force on dissent, protest and community noted that there were “no black students on the board [of editors] and that there was in fact no black voice in the decision” to omit Obama’s inauguration.

Even Asian American students who have joined the Wheel suffer; visual diversity does not necessarily herald the advent of equity, inclusion or belonging. We cannot speak for the broad range of lived experiences at the Wheel, nor should we attempt to do so. But two of us, as South Asian editors, have been met with the “model minority” assumption throughout our time at the Wheel — backhanded comments that “we’re not really minorities” and the unspoken assumption that we’re “passive,” which justify a racialized work distribution and diminished opportunities. Meanwhile, our white counterparts are able to navigate the structures of the Wheel without the same assumptions weighing them down. Throughout our time at the Wheel, we’ve seen or witnessed Asian writers or editors be passed over for opportunities for no clear reason. We’ve heard fellow editors abhorrently question whether or not Asians face racism at all, underscoring a destructive white adjacency that some use to negate wrongdoing on their part.

When BIPOC have attempted to share their stories, they have often been shut down, or worse — they have received threats against their life. Stories that should have been told from BIPOC perspectives were told from those who could not do the subject of the piece justice. Pabbaraju recalls continuously being shut down trying to cover articles concerning race, such as those about Greek life, terrorism and Islamophobia. When Pabbaraju suggested the Editorial Board cover the model minority myth in regard to Harvard University’s (Mass.) affirmative action lawsuit, she was met with apathy, and the resulting piece didn’t deeply delve into those issues. Former Assistant News Editor Namrata Verghese (19C) once tried to cover BIPOC responses to pro-Trump chalkings only to be told that she couldn’t be objective as a person of color. These are just a few of the many challenges BIPOC face in a newsroom built to focus on the white Emory experience.

Multiple former editors in interviews described the Wheel’s culture as extremely “professional.” But it is important to note that these cultures of professionalism are often coded in whiteness. As Balarajan noted in a column earlier this year, standards of professionalism — from dialect to hairstyles to names — are built to uphold white-dominated spaces. While on the surface, professional standards might not seem especially harmful, we must evaluate its adverse historical and institutional impact on BIPOC.

Former Opinion Editor Zach Ball (20C) described the Wheel’s culture as “obliviously exclusive” to low-income students who work additional jobs and lack the means for the hefty time commitment of an editor’s role. He stated the stereotypical Wheel editor or writer is someone who is affluent, white, cis-heterosexual male, and those assumptions undergird how the Wheel operates. Such defaults closely mirror the recruitment measures from the 1960s: while former white editors such as Sexton were able to join the Wheel through word of mouth from a fraternity brother or a dorm mate, Black contributors such as former cartoonist Rob Cleveland (76C) had to actively seek out the Wheel to get involved.

Other white editors, such as former Managing Editor Isaiah Sirois (19C) and former Arts & Entertainment Editor Joel Lerner (20Ox, 22C, 23PH), have described the working environment as “toxic.” Adesola Thomas (20C) stated that while she appreciated the opportunity of being a Wheel editor to diversify content, “in hindsight [she] realized how difficult it was to do the Wheel in addition to being a full time student and having a job.” Several former editors, many of which left the Wheel within the last two years, have cited tenuous working conditions, which can require between 30 to 40 hours a week, as an unreasonable expectation. In addition to these barriers, BIPOC have the burden of navigating white-dominated spaces where their voices are often drowned out or ignored altogether.

Content Warning: The below image contains racial slurs.

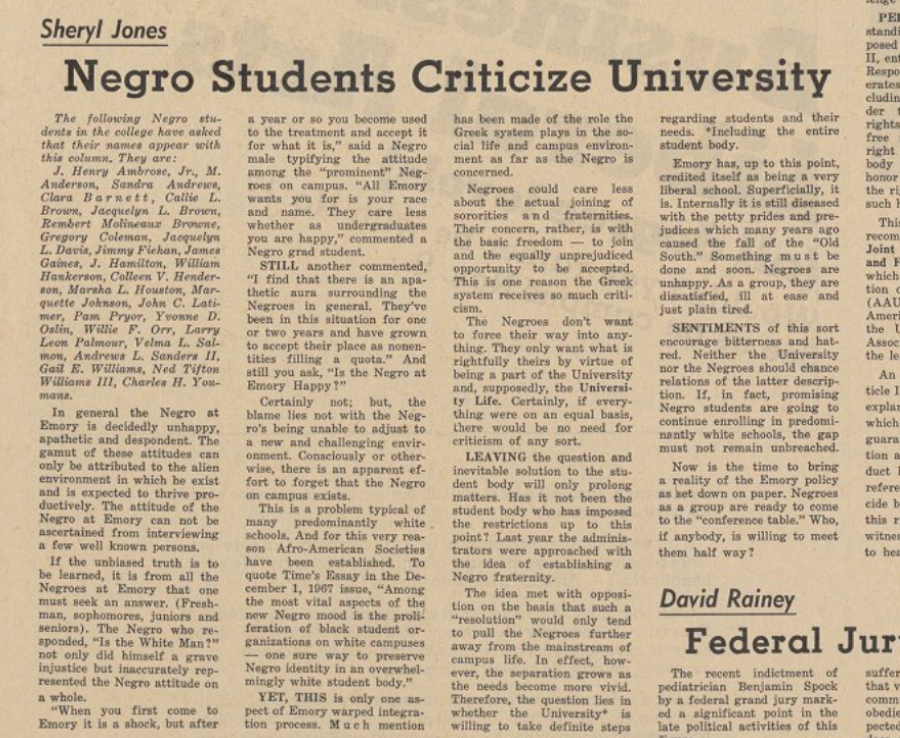

Jan. 18, 1968. Black students jointly condemn Emory’s failures on racism and inequity. Courtesy of the Rose Library.

The etiology of the Wheel’s toxic, white-dominated culture is complex. But of all the factors behind it, the most influential is likely the paper’s decades-long affiliation with Greek life. As writer Sheryl Jones described in a 1968 article along with several other Black students, Greek life is an inherently segregationist structure reflective of the University’s warped integration process. She stated that Black students “could care less about the actual joining of sororities and fraternities. Their concern, rather, is with the basic freedom — to join and the equally unprejudiced opportunity to be accepted.”

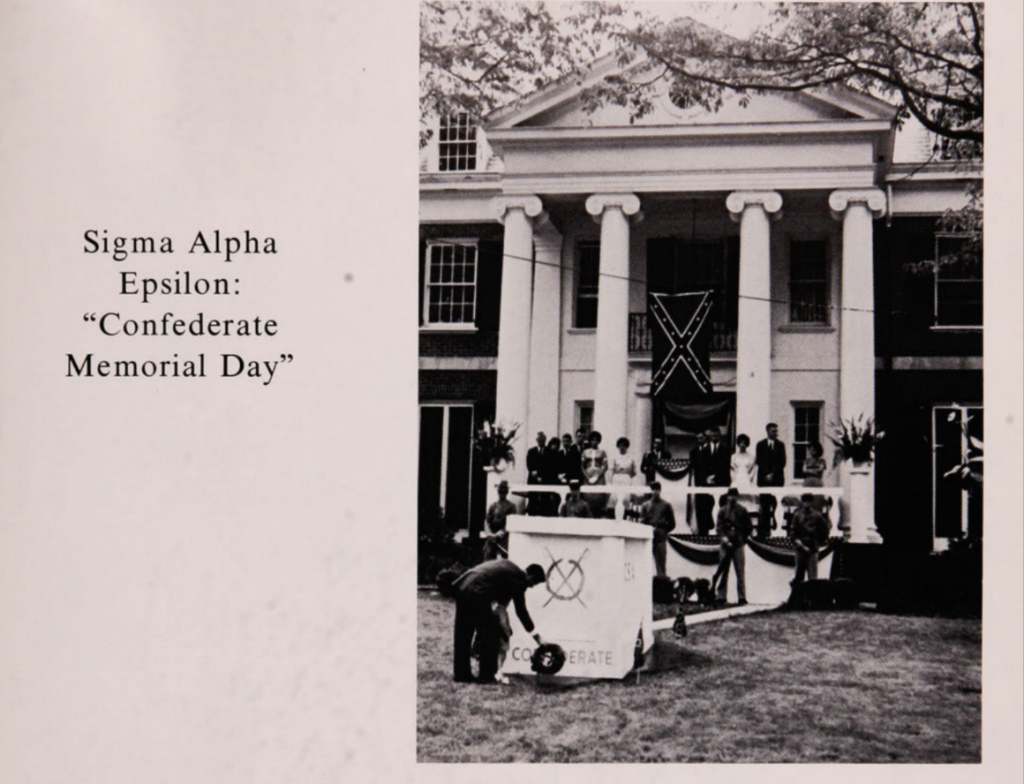

Even non-Black students in the early 1960s recognized the structural racism rampant in Greek life. As former Arts Editor Stan Stockdale (67C) explained, “fraternity rush was eye-opening because some of the fraternities were very open and apparently proud of their racist attitudes.” Given this summer’s illumination of racist practices and exclusionary cultures of many sororities and fraternities, the Wheel’s intersection with Greek life has frequently lent credence to the white-washing of our news.

Many former editors described learning about the organization from older members of their fraternities, and several current editors can say the same. As Lerner pointed out, that so many current editors are or recently were members of Greek life indicates that phenomenon is ongoing. To be clear, we are referring to groups affiliated with the Emory Panhellenic Council (EPC) and Emory Interfraternity Council (IFC), not multicultural organizations, which arose in response to BIPOC’s continued exclusion from social fraternities and sororities. Emory’s social Greek life scene is predominantly white; if we recruit our members from such organizations, we should not be surprised when the Wheel’s demographics and power distribution mirror those of a fraternity or sorority.

Yet the Wheel’s enduring ties to Greek life have ramifications extending far beyond its internal dynamics. Our coverage suffers, too. Just last month, four out of the Wheel’s six executive board members had to recuse themselves from a news article revealing sororities’ gross inaction on diversity, equity and inclusion (DEI) issues because they themselves were or are members of Greek organizations. While most of the editors who had conflicts of interest had either quit their organizations or were currently involved in multicultural Greek life by the time of publication, that should not discount the real harm they have done to communities of color by supporting racially discriminatory institutions and politicians, some of whom have taken photos with KKK members and condemned the Black Lives Matter movement. It does not change the fact that reporting on Greek life issues ethically becomes nigh impossible when so many of the people who oversee that reporting have conflicts of interest with it. We cannot ethically recruit so many of our members, elevate so many of our leaders and taint so much of our coverage with conflicts of interests from social fraternities and sororities when that so consistently reinforces the Wheel’s toxic intolerance and overwhelming whiteness.

Content Warning: The images below contain racial slurs, depictions of racial violence and racism.

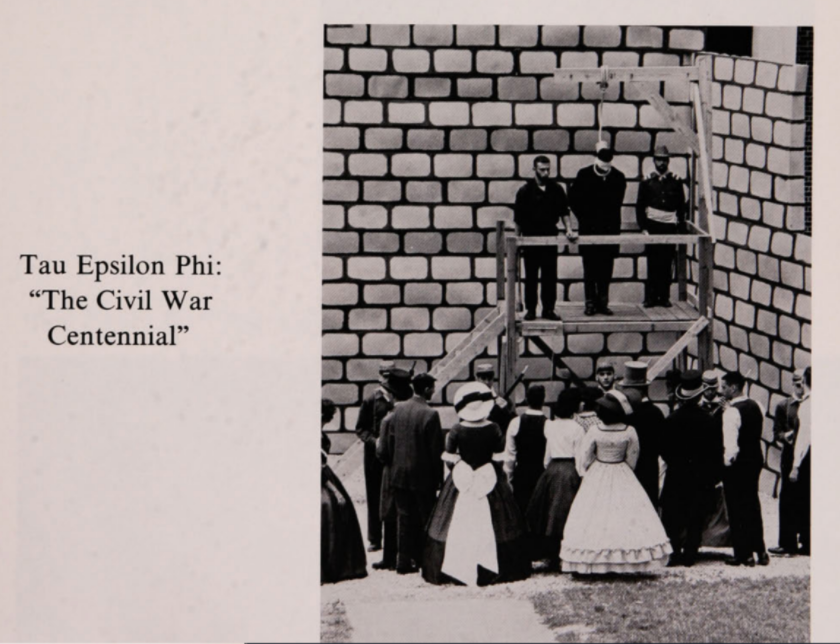

1962. Tau Epsilon Phi hosts “The Civil War Centennial.” Courtesy of the Rose Library.

1962. Sigma Alpha holds a “Confederate Memorial Day.”

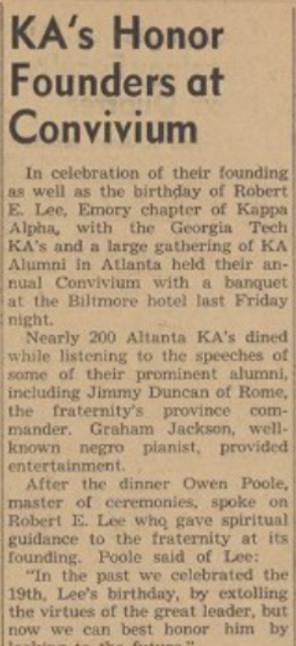

1945. Kappa Alpha (KA) celebrates their “spiritual founder,” Confederate Gen. Robert E.Lee. Courtesy of the Rose Library.

Greek life’s hierarchical culture teaches tolerance of inequity, and the extent to which that pernicious influence has prevented improvements at the Wheel is impossible to understate.

Relationships with communities of color

In many ways, this piece is a miracle. In any other year, it and the larger project “1963” would have perhaps failed to get off the ground for any number of reasons. Following George Floyd’s death last May, white people’s racial consciousness momentarily increased. But BIPOC were already talking about these issues and lived with racial consciousness out of survival. Only after this summer’s protests did discussions of race only became more palatable and less threatening for white audiences. Moreover, last summer allowed white editors to publish race-centered pieces without fear of, as past Wheel editors-in-chief have said, “ruining the respectability of the paper.”

This piece itself faced many roadblocks, such as unfair double standards that affected who we were allowed to interview and biased limitations on the piece’s length and depth. Our efforts reflect a sentiment expressed by journalist Farai Chideya: “So many times, when I tried to cover racial resentment or white nationalism, my editors acted like they were protecting the truth from me. Instead, they prevented Americans from learning the truth.” We solely attribute the publication of this piece to our personal tenacity, our willingness to challenge unjust power structures and the experiences of alumni. For 100 years and counting, the Wheel has suppressed and neglected stories about race that matter, and we are finally, though not completely, bringing many of those to the surface where they belong.

When the Wheel chose not to cover Obama’s inauguration as the first Black president in U.S. history, many Black students protested the Wheel. President Wagner’s task force commented that a student who recalled “the editors’ reasoning [for excluding such coverage], talked about how extensively and painfully they discussed the issue and made the decision.” Additionally, Wagner’s committee also found that a subsequent sit-down between the Wheel and protesting students left an “impression … that [the conversation] didn’t resolve much.”

The Wheel also maimed its relationships with communities of color when editing stories centered around race. Current Editorial Board member Sara Khan (23C) recalled facing setbacks and barriers when writing about her South Asian identity for opinion and arts & entertainment articles. She stated, “in one article I wrote, an editor questioned whether or not my personal accounts of arranged marriage were valid. Although I am happy so many writers are addressing race now, there is still work to be done. Unless the Wheel can prioritize POC editors’ opinions in the editing process for race-related articles, the organization will drive away people of color with their primarily-white, close-minded board of editors.”

Khan is not alone with this sentiment. Balarajan, for instance, wrote weekly columns on topics of national politics from the lens of a woman of color. Frequently, Balarajan found her articles about race going through four white editors. The editing process in itself is overwhelming and can often result in code-switching to surrender to whiteness — a form of erasure. When white editors over-edit our language and experiences, it becomes a form of code-switching, as they invalidate our experiences or make it more palatable to the white ear. Only we, as BIPOC, have the lived experience and language to discuss issues that are deeply personal to us.

This form of code-switching is often evident through our Editorial Board’s stance on issues, which have been too neutral on injustice in the past. Such inaction disrupted our relationship with communities of color and reflects the privilege that the Board upholds. Some writers have the ability to distance themselves from hatred because it doesn’t affect them personally. When conservative commentator Heather Mac Donald came to campus last year, she gaslighted minority students by claiming they were “taught to think of themselves as victims and see bigotry where none exists,” and delegitimized sexual assault survivors, stating that “the vast majority of what is called campus rape is voluntary hookups.” The Editorial Board failed to take an active stance condemning such rhetoric and instead published a watered-down article lamenting the event’s negative impact on free speech.

Too often, journalism avoids condemning and thus bolsters hatred in the name of false objectivity. In that case, our organization has chosen silence, thereby taking the side of the oppressor. But Mac Donald isn’t the only one — when former far-right Breitbart News Editor Milo Yiannopolus came to Emory, the Editorial Board failed to take a strong stance against his views. Instead, the Editorial Board condemned protesters at the University of California, Berkeley, for violating speakers’ free speech at a similar event. However, our Editorial Board has taken stances in this past semester that were suppressed just months ago: calling for the abolition of Greek life, criticizing Emory for failing the Indigenous community and reflecting on the Capitol riot’s embodiment of white supremacy. These takes would not have been possible without the substantial additions of BIPOC voices over this past year. Cleveland said it best: “If you look at your staff at the Wheel and it’s diverse, those stories are going to come.” However, he warned, “you still don’t want to take it for granted. Just because you have a diverse staff, [it won’t mean progress] if all your stories [are] about the magnolia festival.”

Still, the stories we are allowed to tell are at the discretion of leaders whose judgment is often clouded by misguided concerns of neutrality. We have a responsibility to always speak out against injustice, to challenge other organizations that choose to enable platforms for downright racist rhetoricians and those who hammer the nails of white supremacy into the coffin of journalism. Journalism isn’t dying, it is liberating itself, finally beginning to promote anti-racist, accessible content on social media.

As student journalists, we have an opportunity to make just such change at Emory, and we have taken it.

What now?

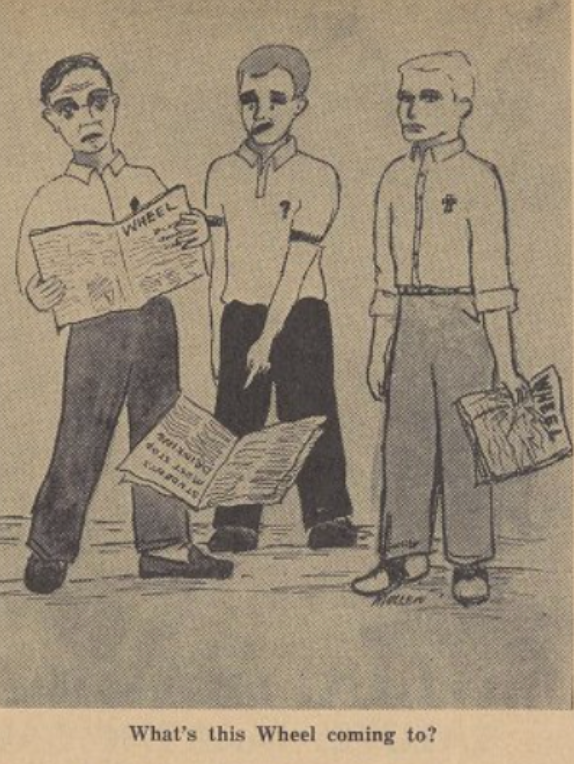

Feb 2, 1962. Comic deriding the Wheel’s evolution. Courtesy of the Rose Library.

Amid last summer’s Black Lives Matter protests, student organizations panicked. Clubs mobilized to prove their commitment to anti-racism. Emory Greek Life made the grand sacrifice of ruining their social media aesthetic to post brief apologies. And the Wheel, unsurprisingly, found itself at a loss on how to reconcile with 100 years of racism.

Its solutions, like sending mass, impersonal emails to BIPOC organizations and students on campus requesting that they write for us, reveal the Wheel’s focus on tokenizing BIPOC rather than enacting substantial internal reform. More than that, it poorly addresses the problem that it purports to solve and is emblematic of the core issue that we expect communities of color to do the internal anti-racist work for us. As Lerner stated, “I wouldn’t dare try to sit down with the editors of BLACKSTAR* because that’s insulting. No, they don’t want to work with us because we haven’t made those internal changes.” In this case, the Wheel’s solutions were eerily similar to what Lorde warned in her article: “I still hear, on campus after campus, ‘How can we address the issues of racism? No women of Color attended.’ Or, the other side of that statement, ‘We have no one in our department equipped to teach their work.’ In other words, racism is a Black women’s problem, a problem of women of Color, and only we can discuss it.”

While the Wheel found it admissible to engage in DEI work following this summer’s protests, BIPOC editors and writers have been doing the work for years — what was truly lacking was institutional support. Adesola Thomas (20C) recalled that she used her editorship to prioritize “diversity [in] our content … [and] highlight the work students of color were putting forth. I was really dedicated to bringing more women onto our staff, more POC, more students who are typically underrepresented in the A&E staff.” However, she also stated that while she “knew that staff writers and the people who wrote for our section valued what we were trying to do, personally it was taxing and exhausting.”

Even with this summer’s springboard to challenge institutional racism, the Wheel’s efforts were lackluster, half-hearted and, frankly, performative. Lerner recalled recommending the creation of a DEI editor position back in June only to be shot down. While the Wheel named a DEI editor and assembled a corresponding task force in the fall, the committee was designated as “opt-in,” as editors are still not required to join. Moreover, the opportunity to join the DEI task force was only publicized twice in passing. This leads to an undue burden on BIPOC editors to commit their time and energy to effect change while most white editors and writers can refrain from engaging in anti-racist work. Of the 31 current editors, many of whom are white, only four non-executive editors chose to join. Lydia Abedeen (21C), after declining the position of DEI editor, stated that “one voice responsible for such a task, responsible for representing such a populace, is not enough. The Wheel needs to stop tokenizing minorities on their staff and start reaching out if they really, truly want to spark change.”

The Wheel’s DEI task force may have had a rocky origin, but that should not diminish its responsibility of undertaking anti-racist work. To its credit, the task force has already begun finding ways to pay editors and create more associate editor positions to reduce editors’ workload; the latter may happen as soon as this semester. But a small group of editors broadly charged with improving diversity, equity and inclusion at the Wheel can only do so much. People think simply setting up a task force will be effective at doing the work needed to be more equitable. But who runs it, what it does and why it works are all important factors to consider. Every editor should be a part of the task force, and as the official voice of the Wheel, the Editorial Board needs to be involved, too. As such, the DEI task force should not even really be a task force; it should divide into smaller project teams that can execute anti-racist work.

Beyond the task force

We all have a stake in the results of DEI efforts, so we should all help the Wheel get there. We should not promote writers to editors unless they are committed to the efforts of anti-racism because they are the first line of checks in ensuring we do not publish hate speech. We also need more than one DEI editor. Placing the whole burden on one individual, no matter their ability, expects too much — how can one individual, despite being from a marginalized background, understand, identify and rectify errors that pertain to the lived experiences of identities that are not their own? Ongoing anti-racist trainings and discussions should be mandated for all editors and writers, as they are the first line of review for every article. We all have a responsibility to actively be anti-racist, and therefore the onus should fall on both writers and editors equally. Moreover, if the Wheel can bring on two assistant editors for almost all of its sections, it can spare room on the masthead for one or two more DEI editors. Claiming we have to limit leadership positions is elitist, anyway.

DEI work should also not begin and end with only a committee or position: doing so would be optic or performative at most. We need a massive overhaul at every level of the Wheel. Both on the task force and generally, leadership matters. In fact, our investigation found that one of the strongest predictors of the Wheel’s inclusivity for students of marginalized communities has been the extent to which editors-in-chief prioritize it. For example, Mooney created the Black Voice column during her time as chief. Before Mooney, many who were on staff earlier in the 1970s made it clear that as the paper’s leaders took no DEI-related action whatsoever, the Black presence on the masthead was negligible. When asked if Wheel leaders had any substantial conversations about DEI during his tenure, former Assistant Editor Dr. Robert Aldrich (75C) flatly stated, “No. Not at all.” He graduated just one year before Mooney. However, it should be noted that Black writers weren’t actively recruited by the Wheel under Mooney — the paper simply made space for them.

To prevent stymying anti-racist work due to a lack of institutional memory, the DEI editors should be involved in all major decisions the Wheel makes, including but not limited to promotions, structural changes and coverage. When it comes to promotions, for instance, we must evaluate who is in the room reading applications for leadership positions, what questions are on the application and for whom the application is marketed. Only then can we ensure equity and inclusion for those navigating the Wheel’s internal structures.

Additionally, the Wheel should onboard between one and three publicity and outreach editors who would be responsible for rebuilding the Wheel’s relationships with marginalized communities and making it more hospitable for the members of those groups. That’s how we’ll be able to bring them into our organization, their voices onto our pages and their stories into the mind of the Emory community. Right now, the Wheel’s general-purpose recruitment efforts consist of a biannual set of interest meetings. With the exception of recruitment for the Editorial Board, which is its own intense process, the rest of the year is focused on coverage. Getting involved in the Wheel should not be conditional on knowing a current editor or happening to drop in on one of the two interest meetings each year.

To mitigate both classism and inhospitality to BIPOC, the Wheel also needs to pay editors. Generations of Wheel staff have testified to the fact that the enormous time commitment of being an editor often prohibits low-income students from joining. Working so many hours per week for free prevents them from taking the jobs they need to support themselves. Many more BIPOC students participate in federal work study than do white students, and Black women have the highest rate of taking on college loans. More BIPOC students are first-generation — 42% of Black students and 48% of Latinx students are first-generation, compared to just 28% of white students. In this way, reducing the Wheel’s financial barriers would also soften its racial ones. Additionally, the Wheel must mitigate unequal access to opportunities by offering funds to pay writers to cover events. For low-income writers, the cost of an Uber and tickets to an arts festival can be a deterrent from expanding their journalistic abilities and rising up at the Wheel. As such, we miss out on their talent and voices.

Such a move isn’t unprecedented — plenty of other college newspapers and even Emory publications compensate writers and editors for their contributions. Harvard’s student newspaper, the Crimson, pays one-third of its staff. Yes, finding the money will be difficult, but not impossible. To do so feasibly, the Wheel should remain digital first, fortify ad revenue and host numerous large-scale fundraisers throughout the year.

The Wheel is Emory’s paper of record; it writes the first draft of the University’s history. But as our investigation and the rest of “1963” has revealed, it hasn’t exactly succeeded in doing so respectfully, objectively or humanely. By dusting off the uncomfortable parts of the Wheel’s history and telling the stories that it once deemed unfit to tell, we have tried to ensure that future generations do not repeat the mistakes of the past or present.

We shouldn’t always look to skewed precedent to guide our organization, as BIPOC were largely excluded in those conversations. Recent conversations around the Wheel constitution’s delineation of staff voting rights, for example, were held around the idea of an exclusionary “precedent.” The Wheel’s past was largely constructed by white, cis-heterosexual male editors. If we want to build a more inclusive organization for the future, we should be wary of hewing too closely to that history.

Now, equipped with a clearer picture of its harmful legacy and carrying what we hope is real momentum, the Wheel must finally commit to becoming the equitable organization that it always should have been.

When we wanted to find out what Emory students were thinking during desegregation, we turned to the Wheel archives. What we found was a largely white-centered point of view. This is a fact, one which still plagues the organization to this day. But our critique of the Wheel should not be discounted for our anger.

For it is not our anger that platformed the Ku Klux Klan at the expense of the humanity of BlPOC students. For it is not our anger that hides behind a DEI task force to feign addressing structural and cultural racism. For it is not our anger that name-calls, jeers, mocks and makes snide comments toward students radically overhauling the Wheel. For it is not our anger that mistreated generations of marginalized Wheel alumni. For it is not our anger that wrote BIPOC students and their stories out of existence.

By Brammhi Balarajan (23C), Shreya Pabbaraju (21C) and Ben Thomas (23C).

Brammhi Balarajan and Ben Thomas are the Wheel’s Opinion editors. Shreya Pabbaraju previously served as managing editor for Opinion and Arts & Entertainment.

Rachel Broun (23C), Martin Li (22Ox) and Sophia Ling (24C) contributed reporting.

Lydia Abedeen (21C), Robert Aldrich (73C), Zach Ball (20C), Randy Blazak (83Ox, 85C, 95G), Benie Colvin (66C), Mark Chester (74C), Rob Cleveland (76C), Debbie Cook (67C), Rodney Derrick (69C), Ben Dansker (74C), Alan Gordon (77C), Amos N. Jones (00C), Sara Khan (23C), Joel Lerner (20Ox, 22C, 23PH), Brooks Miller (77C), Stephen Mizroch (72C), Brenda Mooney (76C), Mark Rovner (77C), Mike Sager (78C), Richard Sexton (75C), Isaish Sirois (19C), Bruce Sternberg (67C), Stan Stockdale (67C), Adesola Thomas (20C) Otis Turner (69T, 74G) and Namrata Verghese (19C) were interviewed or supplied insight for this piece.

This article is one part of “1963,” an investigative opinion project. Read the rest here.

Brammhi Balarajan (23C) is from Las Vegas, majoring in political science and English and creative writing. She is the Editor-in-Chief of The Emory Wheel. Previously, her column "Brammhi's Ballot" won first place nationally with the Society of Professional Journalists. She has also interned with the Georgia Voice.

Such important work worthy of reading. Thankful that these authors have gone out of their way to address these horrific realities. I especially cannot get over the part about editing out BIPOC voices through multiple rounds of white editors. Thank you!