Last November, the Student Bar Association (SBA), Emory Law School’s student government, rejected a charter request by the Emory Free Speech Forum (EFSF), a nonpartisan student group committed to providing a platform for different perspectives on various issues.

Now, the governing body is under fire from national free speech organizations accusing the group — and by extension, Emory University — of infringing on their rights to free speech and academic freedom.

SBA, composed of around 30 students, held two chartering hearings for the forum, on Oct. 20 and Nov. 3, both times voting against the charter request. In a letter to the free speech group, SBA wrote that it denied the charter because the group’s goals overlapped with other established clubs. SBA also said it was also concerned with the lack of safeguards, such as moderators, to facilitate discussions.

Having a charter would mean that the organization could receive University funding, use University spaces and advertise at the school’s activity fair.

After leaving the first hearing, the forum’s president, Michael Reed-Price (24L), said he was concerned that SBA members were not as enthused about free speech as he expected.

“SBA doesn't have to agree with us, they just have to appreciate our ability to have these conversations,” Reed-Price said.

The group’s vice president MacKinnon Westraad (24L) said the forum’s purpose was to allow students “to hear the minority opinion, hear the opposing side, be enlightened on all sides of the story.”

Some First Amendment scholars have sided with the forum, arguing that SBA’s actions violated free expression principles because SBA functions as a governing body for the University.

Though the forum is not chartered, the organization still plans to hold meetings off campus.

SBA’s concerns

SBA, which unanimously rejected EFSF’s charter request in the first hearing, argued that certain debates about identity cannot occur in a safe way, as proposed by the forum.

“It is disingenuous to suggest that certain topics of discussion you considered, such as race and gender, can be pondered and debated in a relaxed atmosphere when these issues directly affect and harm your peers’ lives in demonstrable and quantitative ways,” SBA wrote in the letter.

The Wheel reached out to SBA President Jadyn Taylor (23L) and three other board members for interviews, all of whom denied to comment or did not respond.

Anticipating this concern, Reed-Price said the forum “made it very clear that our goal is not to inflame [but] to be bridge builders, be unifying, by letting different voices and perspectives be heard.”

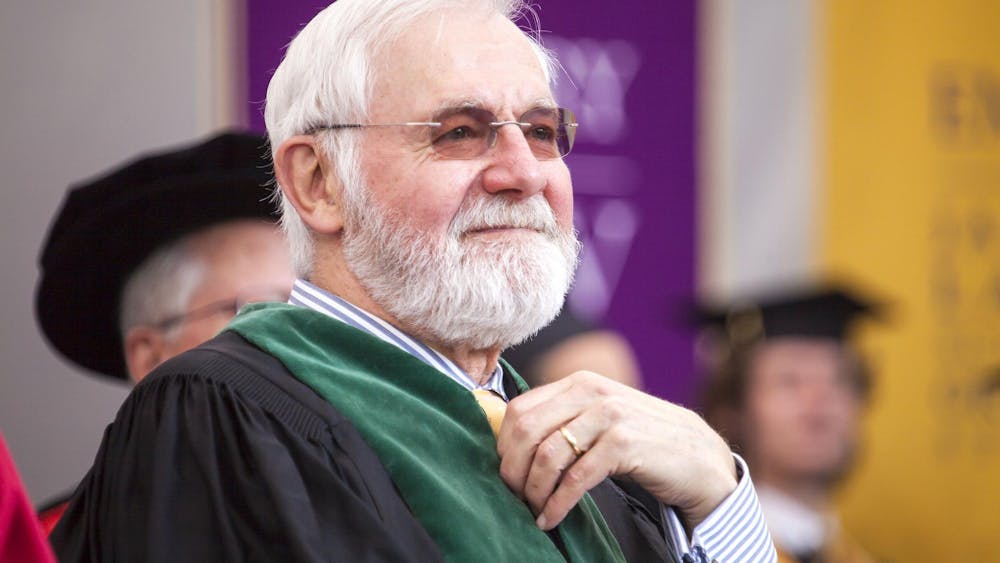

Asa Griggs Candler Professor of Law David Partlett, the forum’s faculty sponsor and former dean of the law school, said SBA’s decision was disappointing.

“I’m not at all a supporter of right-wing agendas, or any other agenda, but a support of people engaging in free speech and intelligent, cogent arguments around the issues of the day,” Partlett said. “If law students aren’t encouraged to do this, there is something wrong with legal education.”

Reed-Price said SBA’s indication that these topics shouldn’t be talked about is “a shame to the idea of a University where you examine ideas critically.” He also viewed SBA’s suggestion to implement mediators as “condescending.”

“A mediator is going to tell us how we can say things and what we can say, which is antithetical to the whole idea,” Reed-Price said. “We would just want … to be treated like adults who can handle ourselves having academic, intellectual conversations.”

SBA also wrote that the forum “overlap[s] considerably” with several other organizations at the law school, which came as a surprise to Reed-Price, who said there was no nonpartisan discourse, free speech or First Amendment organization at the activity fair.

He also believes the forum does not overlap with clubs like the Federalist Society and the American Constitution Society because it is nonpartisan.

Involvement of free speech experts

The forum took SBA’s critiques and edited its proposal, presenting it at a second hearing on Nov. 3. Westraad said the group was denied a charter shortly after without an explanation from the SBA.

Confused by the rationale behind SBA’s issues, the forum subsequently communicated concerns to law school administrators. The group's leaders scheduled a meeting with Associate Dean of Academic Programs Lesley Carroll, which was canceled at the last minute without explanation, according to Reed-Price and Westraad. They said they have not heard from the administration since.

The forum then contacted free speech organizations, the Foundation Against Intolerance and Racism (FAIR) and the Foundation for Individual Rights in Education (FIRE), for assistance in communicating with administrators.

Managing Director of the Legal Network at FAIR Letitia Kim wrote a letter to Taylor on Jan. 18, urging the board to reverse their decision to reject the free speech forum’s charter proposal.

“Over its history, the SBA has approved student organizations with a broad range of focuses, including aviation, LGBTQ+ issues, banking and finance, entertainment, national security and many others,” Kim wrote in the letter. “Noticeably absent is a group whose purpose is to share diverse perspectives, participate in civil dialogue despite those differences, and learn from each other. The EFSF would fill that space.”

On Nov. 1, FIRE Senior Program Officer Zach Greenberg wrote a letter addressed to Taylor and the rest of SBA explaining why he believes the governing body violated EFSF’s rights.

Greenberg said he believes the SBA violated Emory’s Respect for Open Expression Policy and Law Student Handbook by denying a charter on the basis of the group’s goals.

While Emory does not have to enforce the First Amendment as a private institution, Greenberg said the school’s open expression policies mean Emory is “morally and legally obligated to provide students free speech rights” through groups like EFSF.

“Student governments through the university cannot deny groups, cannot reject their recognition, because of the viewpoints or the mission statement of the group, which is good because groups should be recognized in a viewpoint-neutral manner,” Greenberg said.

After FIRE did not receive a response from SBA, Greenberg sent the letter to Bobinski but did not hear back.

In a statement to the Wheel, the law school said the University announced a pandemic-related moratorium on the chartering of new student groups, which is in effect until at earliest March 15.

The law school’s statement did not address last fall’s developments, when the initial hearings took place.

Value of free speech on campus

John Wilson, a former fellow at the University of California National Center for Free Speech and Civic Engagement, also said denying a charter to EFSF violates the principles of free expression. While he said that individuals like professors have power within their individual realms like classrooms, he said this power does not extend to institutions like SBA that have purview over organizations as a whole.

“What a free University has to stand for is giving people the freedom to do things that some people may think are hurtful or insensitive,” Wilson said. “The freedom of expression belongs to those individuals of the student groups, of those organizations and not to the institution.”

Professor of Law at the University of California, Los Angeles Eugene Volokh said that SBA operates on an institutional level since it exercises governance power within the University. Therefore, he said that SBA’s denial to recognize EFSF violated academic freedom, given the government’s hesitancy to see race and gender be freely debated.

Volokh continued that free speech at a law school is vital for students to become effective lawyers because an attorney needs to understand the other side’s arguments to best argue their own position.

“I’m afraid that the law school student government is promoting an attitude that is going to ultimately be more harmful to people’s abilities as lawyers and to those people’s clients precisely because it leads them to think that the right thing to do is to shield themselves and to shield others from views they find offensive,” Volokh said.

Students could also be reluctant to engage in challenging discourse out of fear that they will be boycotted or alienated by their peers, Volokh added. Therefore, he argued that free speech originating from a neutral body like EFSF is necessary to broaden the scope of campus discussions.

Beyond the material importance of difficult conversations and the vitality of upholding the First Amendment on college campuses, Reed-Price emphasized free speech as a quintessential mechanism to unite individuals.

“Free speech can be unifying and can be a real bridge builder because when you have these conversations you learn that people are more than their beliefs,” Reed-Price said. “Learning where people come from — standing in their shoes — is a great way to increase tolerance and understanding of other people.”

Madi Olivier (she/her) (25C) is from Highland Village, Texas, and is majoring in psychology and minoring in rhetoric, writing and information design. Outside of the Wheel, she is involved in psychology research, the Emory Brain Exercise Initiative and the Trevor Project. In her free time, you can find her trying not to fall while bouldering and obsessively listening to Hozier with her cat.