“Named for the second and fourth presidents of Emory College, Longstreet-Means Hall replaced a residence hall constructed on the same site in 1955.

Augustus Baldwin Longstreet was a well-known lawyer, minister and author, whose book “Georgia Scenes” became a best-selling picture of early Georgia life and earned him a place in the Georgia Writers Hall of fame. He was an advocate for states’ rights and an apologist for slavery. He helped keep Emory afloat with his own funds.

Means was a scientist and medical doctor as well as a Methodist minister. He taught science at Emory and later taught at the Atlanta Medical College.”

Accessible via Emory’s History and Traditions website, the above is a commentary on the origins of the freshman residence hall that students call “LSM.”

This commentary does not deny the horrors committed by Augustus Baldwin Longstreet and Alexander Means. It acknowledges the complexities of their legacy and service. Yet beneath seeming impartiality remains a dark and uncomfortable sense of what has been left unsaid — of what has gone unacknowledged.

Yes, these men were University presidents. Yes, they were instrumental in the development of Emory. And yes, they were slaveholders. But in the three paragraphs above, only the last fact is omitted.

Why did Emory’s trustees decide to bestow these names on this building just 10 years ago? I cannot say. All I know is that these names evoke a kind of pain and violence that is unbefitting of a University building and difficult for me to swallow. LSM’s name must change.

Of course, Emory’s history, like that of the United States, is steeped in the legacy of slavery.

“Emory acknowledges its entwinement with the institution of slavery throughout the College's early history,” the executive committee of the Board of Trustees wrote in its 2011 Statement of Regret. “Emory regrets both this undeniable wrong and the University's decades of delay in acknowledging slavery's harmful legacy.”

As historian Mark Auslander claimed in a report by Debra Krajnak, the founding of Emory by Methodists in 1836 was rooted in the contradictory practices of religion and slavery.

“There was no question that slavery was part and parcel of the founding of Emory College,” Auslander asserts, noting that although the College never owned slaves, records show it rented them.

Emory should continue to acknowledge its early contributors and all their inherent contradictions. But there is an important difference between acknowledgment and praise. On June 27, Christopher Eisgruber, the president of Princeton University (N.J.), announced the removal of Woodrow Wilson’s name from the University’s School of Public Policy and International Affairs as well as one of its residential Colleges.

“When a university names a school of public policy for a political leader, it inevitably suggests that the honoree is a model for students who study at the school,” wrote Eisgruber. “This searing moment in American history has made clear that Wilson’s racism disqualifies him from that role.”

The names and stories we choose to foreground are the ones that define us. Though we cannot change our history, we can shape its narrative. As long as the institution stands, we may never forget the important contributions made by Emory’s early leaders. While we continue to remember these leaders’ names, we must also remember the violence that they inflicted.

When we name a place after someone, we pay homage to them. Yet in honoring Emory’s early leaders without illuminating the truth of their crimes, we tell only half of the story. We ignore the violence of the past, and in so doing, we inflict further violence. We create more pain.

“Princeton honored Wilson not because of, but without regard to or perhaps even in ignorance of, his racism,” Eisgruber acknowledged. “That, however, is ultimately the problem. Princeton is part of an America that has too often disregarded, ignored or excused racism, allowing the persistence of systems that discriminate against Black people.”

In Auslander’s essay, “Dreams Deferred: African-Americans in the History of Old Emory,” he includes a list of names: “Albert (b. 1818), Fanny (b. 1828), Harriet (1852-1861), Iverson (b. 1858), Samuel Means, Henry Robinson (b. 1806), Cornelius Robertson (b. 1836), Ellen Robertson (b. 1835), Milly Robinson (b. 1811), Mildred Robinson Pelham (b. 1836), Thomas Robinson (b. 1850), Troup Robinson (b. 1852), Thaddius and Anna Tinsely.”

These are the names of Alexander Means’s slaves. They are not recorded in the above description of LSM’s origins. I’ve never heard of them. Their labor, however, has both directly and indirectly contributed to Emory’s development and well-being.

As Auslander states, “Excluded by law and custom from the ranks of students and faculty, African Americans were nonetheless a vital presence in the institution — in slavery and in freedom. They served as builders and laborers, groundskeepers and cooks, washerwomen and maids, mechanics and carpenters, chauffeurs and caretakers.”

He also states that “in some instances, it has been possible to trace the descendants of these enslaved men and women, among whom are African American families whose members have been involved with Emory for generations.”

For 10 years, LSM has feted the names of two slaveholders. For 10 years, this has been wrong. But right now, as people refuse to let the names of George Floyd, Breonna Taylor and Ahmaud Arbery fade into oblivion, they lay bare the stories of those lives lost in radical preservation of their humanity. Now is the time for reflection and change. Emory must take bold action and wholly come to terms with the immeasurable violence it itself has committed.

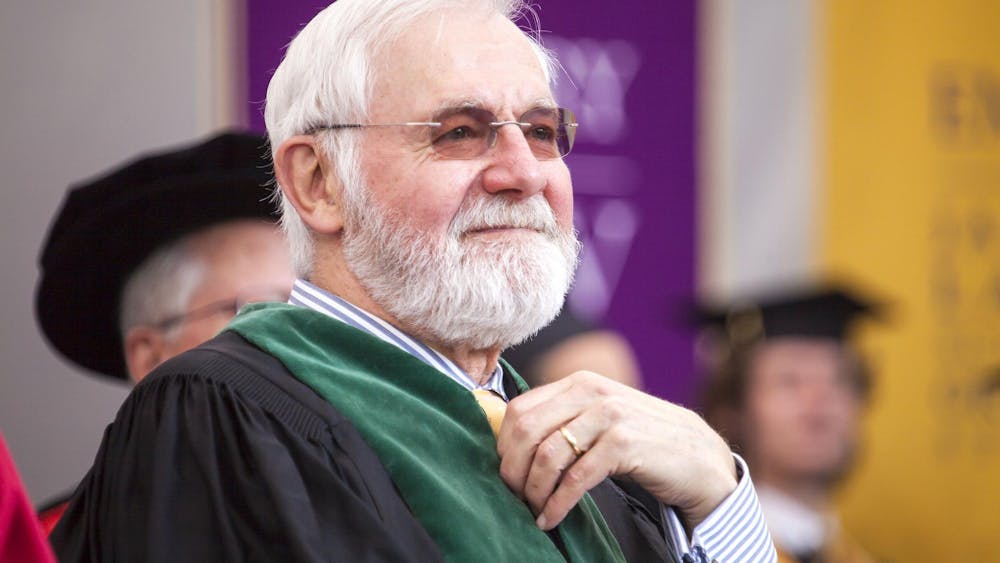

In his recent letter to the Emory community, president-elect Gregory L. Fenves wrote, “I have much more to hear and learn from you about Emory, and we — as a university community — have much more work to do to fulfill our obligation to be a university that leads and prepares those leaders needed for a more just society.”

I challenge Fenves to stick to his commitment to leadership. I challenge both him and the Board of Trustees to rename LSM and take the first step in this journey toward “a more just society.” I challenge the University to decide what narratives it wants to construct and what names it wants to honor.

Kamryn Olds (22C) is from Annandale, Virginia.