Art history is a small yet significant department here at Emory, and its professors possess a rich and diverse array of expertise that is impressive in its own right. However, it is the student engagement with the rich knowledge base available in the art history department that brings the professors’ expertise to life. The conversations, research and reciprocal growth that flourish between student and teacher is invaluable.

On the evening of April 19, the Art History Club hosted its speaker series entitled “Professor’s Choice,” featuring lectures by department professors Elizabeth Pastan and C. Jean Campbell, as well as a brief lecture by Cody Houseman, a PhD candidate at Emory specializing in Roman and Greek art. This lecture series exemplified the impressive sharing of expertise from student to teacher and the conversations that can ensue.

Houseman began the event with a brief discussion about his PhD research in sculpting techniques and inscriptions on Roman cinerary urns. Houseman is in his seventh year of the PhD program, so the depth and breadth of his research were apparent. His examination of evidence was fascinating, including his analysis of not only cinerary urns, but carving tools and sarcophagi as well, noting the symmetries, measurements and writing evident in each.

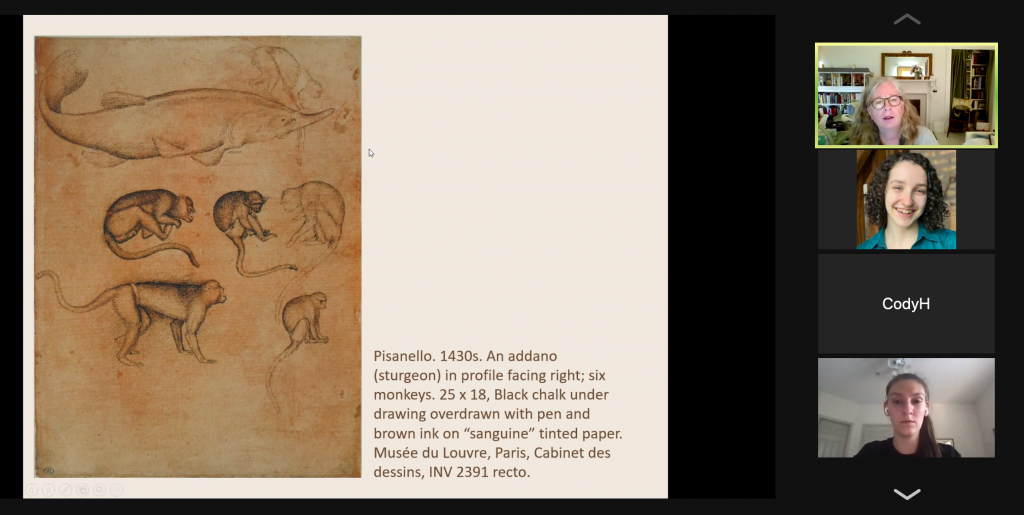

Campbell’s section followed Houseman’s, and despite their different areas of research, there were key similarities between their historical evidence examinations. This section was titled “Drawing Methods and Materials,” and Campbell dealt with late medieval and Renaissance Italian drawing materials and themes of Pisanello, an artist about whom she is writing a book. Campbell examined Pisanello’s intentional use of specific drawing materials; in the first animal sketch that she introduced, she highlighted how he used black chalk layered with pen and brown ink to fix it to the “sanguine” paper, establishing a ground for the drawing and allowing the marks to stick to the paper. This intentional choice of material allowed the subject to shine, but oftentimes, the subject of the drawing also highlighted the material’s surface. For example, the bumpy vellum surface of his silverpoint drawing was emphasized by the curvature of snail shells drawn on the paper, as he pulled the fluidity of the preparatory medium into the finished drawing. The relationship between drawing and material was and still is reciprocal.

Campbell discussing Pisanello’s drawing of monkeys, 1430s. (The Emory Wheel/Zimra Chickering)

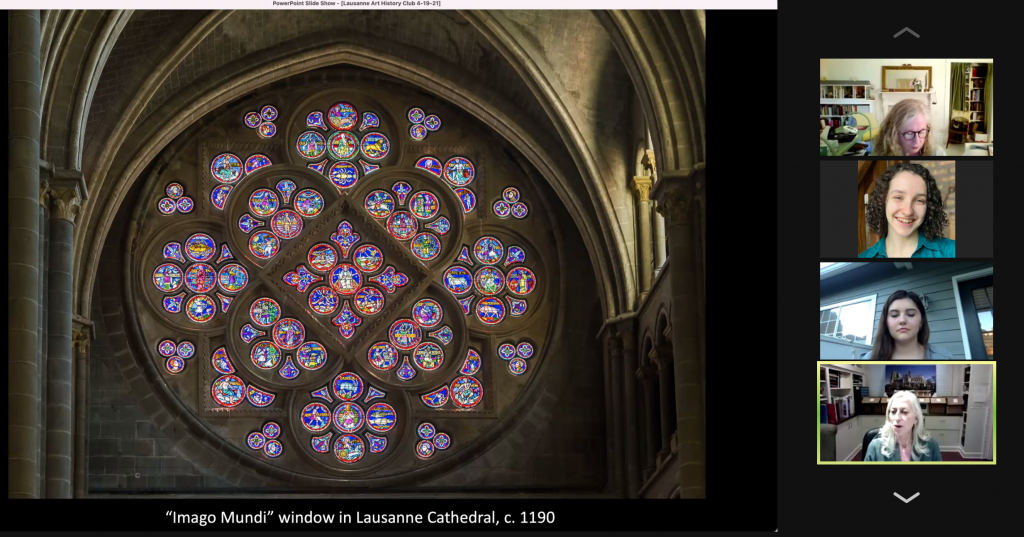

Following Campbell’s thought-provoking lecture was another intriguing discussion led by Pastan. Pastan has been teaching at Emory since 1995, and her comfort in front of the students shone, as she seemed extremely enthusiastic to share her expertise on medieval stained glass. Pastan’s section was titled “On the Rose Window of the Lausanne Cathedral,” and addressed the “Imago Mundi,” or window of the world, in the Swiss Lausanne Cathedral. Pastan noted that the “Imago Mundi” is the most cited Rose Window in the world because it maps out the universe through its incredible depth of symbolism. All of the circular symbolic elements within the window are relatively the same size, and many relate to the concept of time passing, featuring imagery such as the winds, the elements and the labors of the month. The “Imago Mundi” is the only window that uses this circular form of stained glass to create such an ornate depiction of the cosmos.

Pastan discussing the Lausanne “Imago Mundi.” (The Emory Wheel/Zimra Chickering)

Not only is the Rose Window beautiful inside, but its prominence on the exterior of the church serves as an outside advertisement, enticing people to enter. Interestingly, it is much harder to view the window from inside. You are provoked by the exterior, but you must have special permissions to see it on the interior; the window can only clearly be seen by the resident clergy and the people sitting in the front pews. Pastan explained the necessity of noting the setting and placement of an artwork, rather than just the artwork itself. She recalled the writings of art historian Yve-Alain Bois, explaining that if one reduces an artwork to a mere flat photograph, this temporal experience is denied. This emphasis on the physicality of such artworks is not commonplace but is a critical and enriching way of exploring art.

After leaving this lecture, I felt lucky to have experienced the new perspectives raised by these academics, whether it be the parallels of drawing and medium in the Italian Renaissance or the internal and external roles of a famous Gothic window. While scrolling on Twitter afterward, I happened upon a quote from one of my favorite artists, José Clemente Orozco, that perfectly described the energy and intention of this lecture series: “Art is knowledge at the service of emotion.”

Zimra Chickering (24C) is a born and raised Chicagoan who studies art history and nutrition science. She is also a student docent for the Michael C. Carlos Museum, Woodruff JEDI Fellow, educational committee chair for Slow Food Emory, and Xocolatl: Small Batch Chocolate employee. Zimra loves cooking, visiting art museums, photography, doing Muay Thai, drinking coffee, and grocery shopping. She uses writing as an outlet to reflect upon issues and oppurtunities within artistic institutions, and the unique ways in which food and art can act as communicators of culture.