From Aug. 15 through Nov. 8, the High Museum of Art hosted an exhibition entitled “Picture the Dream: The Story of the Civil Rights Movement Through Children’s Books.” The dream referenced in this special exhibition’s title is the dream of equality that Martin Luther King Jr. preached in his famous “I Have a Dream” speech, whose history and future this exhibit reflected upon by highlighting its presence in source material ranging from children’s comics to picture books. The exhibition made the civil rights movement accessible, understandable and actionable for the museum’s younger visitors through its use of relatable imagery and visually-enticing artwork. “Picture the Dream” both honored the past and presented us with steps for the future.

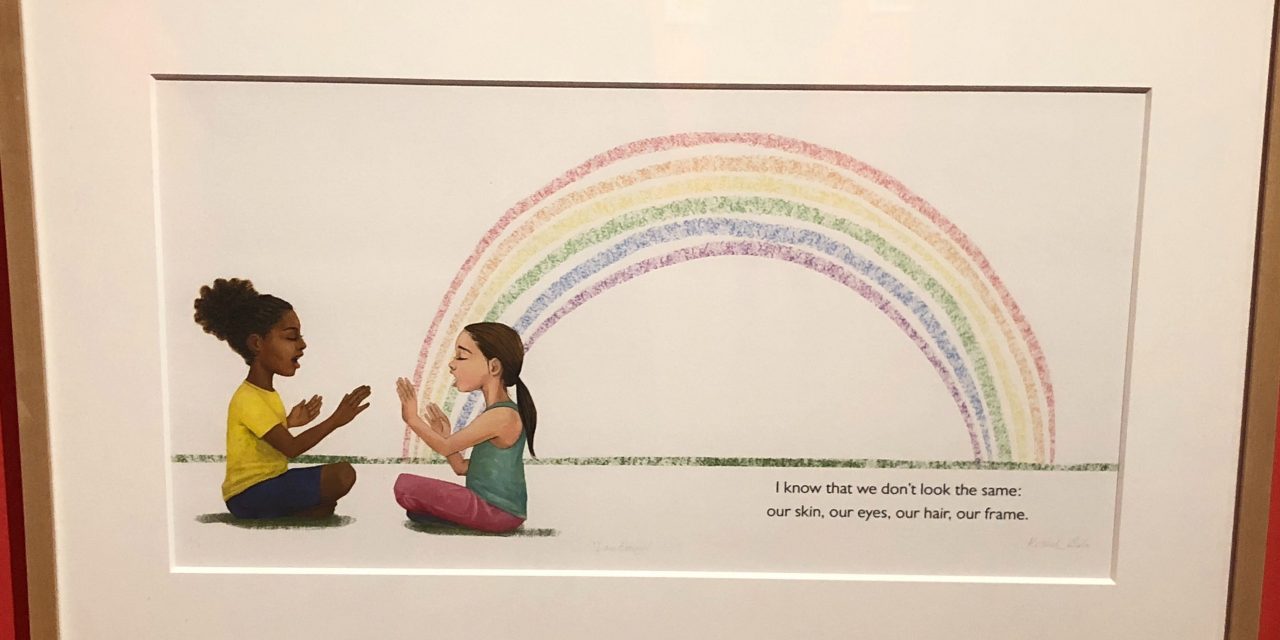

An illustration by Raúl Colón from “Child of the Civil Rights Movement,” 2010, at the entrance of the High Museum of Art exhibition./Zimra Chickering, Contributing Writer

Prior to entering the exhibition, visitors were met by an enlarged image created by Raúl Colón for the children’s book, “Child of the Civil Rights Movement.” The imagery of the crow, reminiscent of the Jim Crow laws, looms from the sky and threatens the rights and the existence of the young child. Yet, the child peers toward the horizon, reaching out with an open heart to an invisible being. Kids traditionally reach past barriers of race and segregation that society attempts to impose upon us all at a young age. This exhibition celebrated children’s ability to treat each other fairly and to forge a new future devoid of the same forms of hatred as the past. By placing this image at the entrance to the galleries, the central message of this exhibition, one of forging a more equal future, was captured very well prior to even entering the space.

In addition to imagery of Jim Crow laws, the exhibition also featured artworks that played with imagery of American flags, churches and water. The use of such imagery allowed for visitors to understand the deep, dark histories of racism in the United States in a way that transcended education level, societal understanding and even political ideology, as these visual cues were simple, overt and did not require any text comprehension. For example, while waiting in line for the exhibition, visitors passed by an artwork that featured diverse children collaged together across the stripes of the American flag. This image rewrites the narrative of what the American flag can represent, beyond just national pride, as the artist superimposes the children, representing the future of the United States, onto the American flag in a way that may not have been accepted by past racist ideologies of segregation and slavery in America.

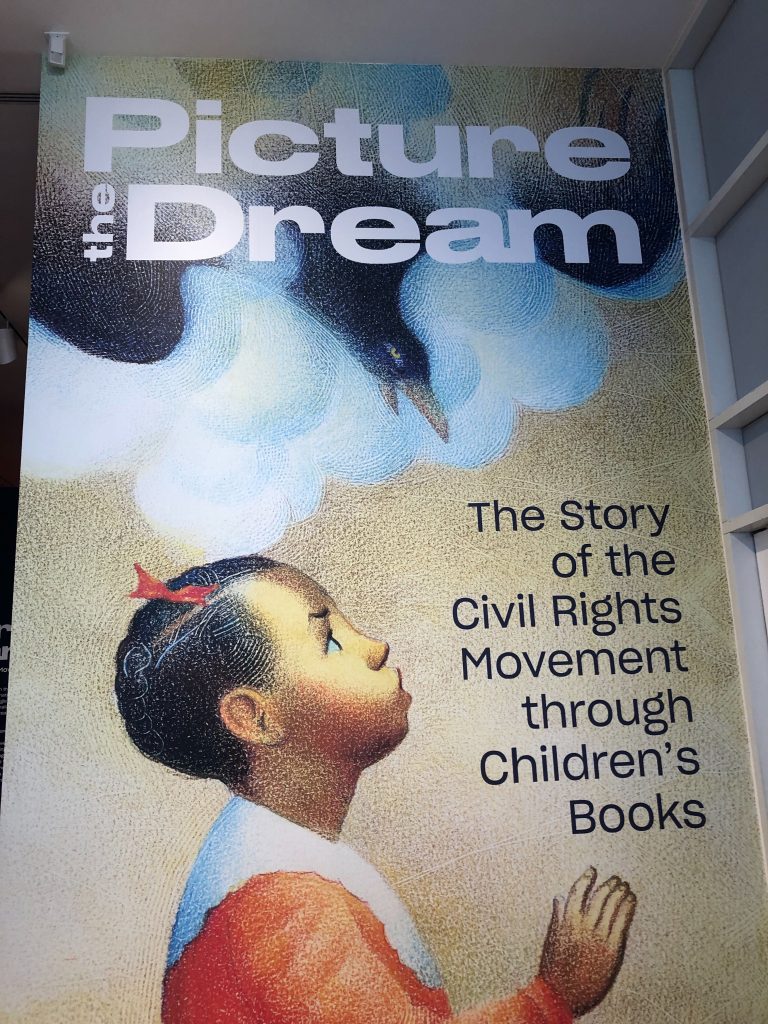

Upon entering the exhibition itself, visitors engaged with a myriad of artworks explaining the origins and history of racism and segregation. This section was entitled “A Backward Path,” and continued the exhibit’s theme of using easily accessible imagery found in children’s books to address the horrors of racism, resorting even simply to the emotional weight carried by different colors. As the gallery label for the below artwork explained, “Faith Ringold’s exaggerated colors convey the gross injustice so many faced. Green water, the color of envy…”

The artworks in each room were paired with small text blurbs that often ended in simple calls to action for the audience, helping visitors connect the events of the past to the necessities of the present. For example, the text featured in the “A Backward Path” section explains how we must learn about the backward paths of segregation and racism in America in order to fix them and forge a better path forward. The exhibition label implored visitors to, “Please pay attention. Because the only way forward is to get a good look at where it all began.”

One of the most striking examples of this reflection was Ekua Holmes’ illustration from the book, “Voice of Freedom: Fannie Lou Hamer, Spirit of the Civil Rights Movement.” The striking imagery of the billy clubs raised to attack civil rights crusader Fannie Lou Hamer as she pleads for mercy and guards her head is both comprehensible enough for the minds of even the youngest museum visitors and yet also graphic enough to induce murmurs of horror from the oldest visitors.

An illustration by Ekua Holmes from “Movement,” 2015, on display at the High Museum of Art./Zimra Chickering, Contributing Writer

While I felt this exhibition was generally successful at tracing the origins of racism and the civil rights movement, I did feel that at times the exhibition glorified the white figures of the civil rights movement. In hopes of including the broadest audience possible, I worry that the exhibition organizers failed to acknowledge how even white and Black civil rights protestors were treated differently due to systemic racism inherent in America’s justice system. For example, a collage by Charlotta Janssen depicted the mug shot of a white woman and was accompanied by a label that said, “…mug shots were color-blind.” While I admire the inclusion of all types of civil rights supporters, I felt it was a large leap to say that mug shots are color-blind, especially considering the fact that inmates of color are often treated worse than their white counterparts, and that people of color are incarcerated at five times the rate of whites.

After the exhibition’s reflection on the beginnings of the civil rights movement, the next room expanded upon the movement’s next stages. Images in this room included a children’s book illustration that addressed Bloody Sunday at Edmund Pettus Bridge and a portrait of Coretta Scott King from the book “Coretta Scott” by Ntozake Shange. The exhibit’s bright red walls paired well with the vivid colors of the artworks in this section. The bright yellow of the Edmund Pettus Bridge was chosen to show “…that the sun’s light shines on those whose resolve would never lose its brilliance,” explained the gallery label, and the bright blue background of Coretta Scott’s portrait shows her forward-looking hope for a better future. These colors brought the narrative of the exhibition to life.

I felt that this section of the exhibition greatly mirrored the actions of Black women in the 2020 presidential election, as the resolve of young voters of color and established Black politicians like Stacey Abrams were the driving factors that spurred President-elect Joe Biden’s victory and created hope for a different future. One piece by Shane W. Evans from the book “Lillian’s Right to Vote: A Celebration of the Voting Rights Act of 1965” celebrated the power of the vote in this section, just as we saw in this year’s election. “Voting is one way people use their power to bring about change. … Black citizens let their voices be heard,” explained the exhibition label.

In the 2020 election, Black citizens certainly did so, as 88% of Black voters under 30 voted for Biden. 87% of Black voters overall backed Biden and battleground cities key to Biden’s victory like Detroit, Atlanta, Cleveland and Milwaukee all had sizable Black voter turnout. Black voices were heard in this vote, despite continued barriers and rampant voter suppression.

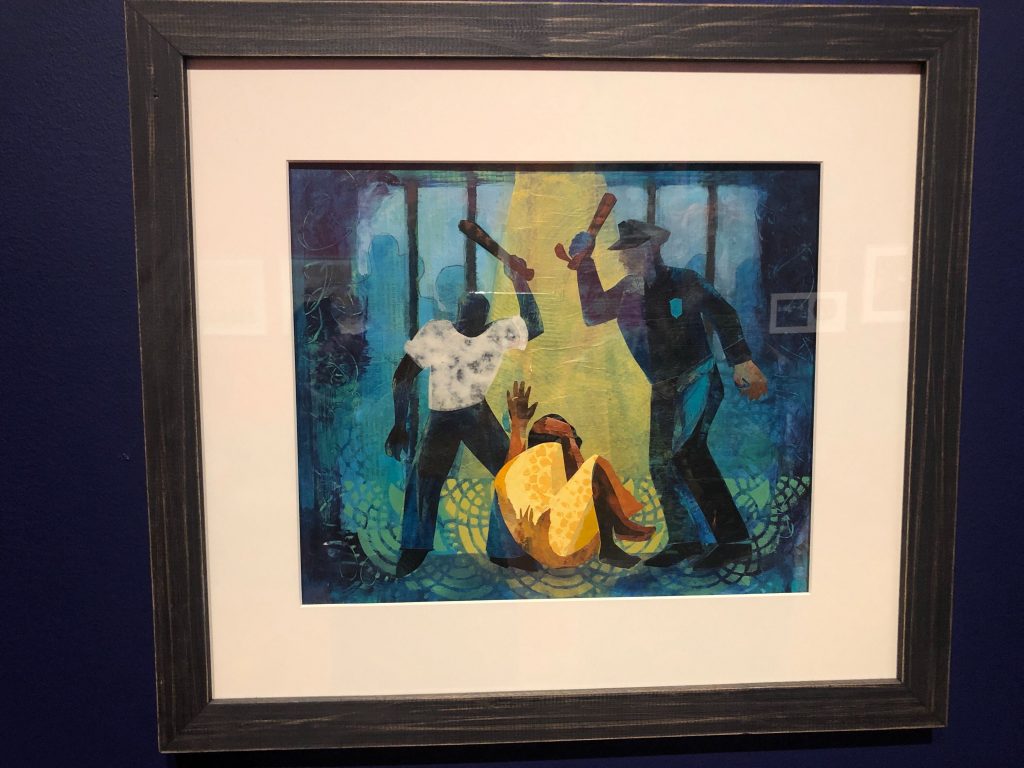

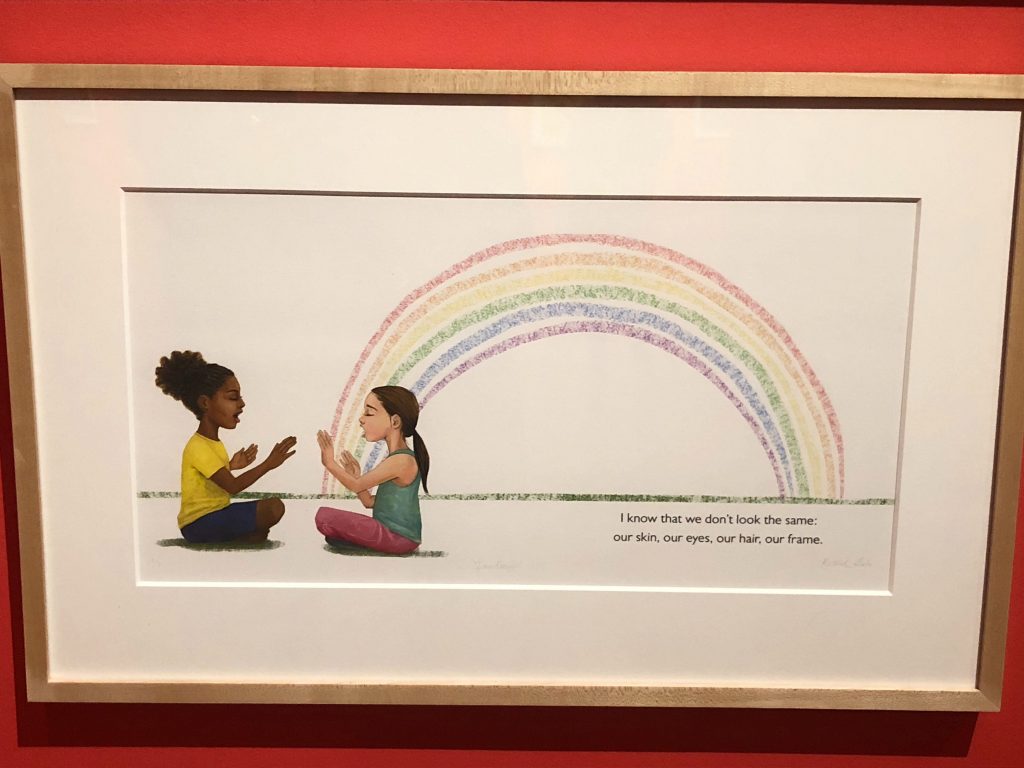

Not only did this exhibition encourage voting as a means of creating a more equal future, but it also implored all visitors, young and old, to take the necessary steps of learning from and appreciating our differences. As the illustration from Grace Byers’ “I Am Enough” book so eloquently highlights, the worth, joy and communication of two little girls of different races is not dictated by their differences. Their differences are acknowledged, as “color-blindness” is never the solution, and they are instead respected, celebrated and shared between the two female protagonists.

An illustration by Keturah A. Bobo from “I Am Enough,” 2018, on display at the High Museum of Art./Zimra Chickering, Contributing Writer

The best summary of this exhibition was provided by a video featured in the middle of the gallery that explained to visitors how it’s important that the youth knows “where these conversations began, to help them determine how to take the conversation forward.”

While waiting in line for the exhibition, due to the staggered entrance times for COVID-19 safety, I saw many families with young kids and I felt hopeful that these accessible artworks would sprout seeds of respect in the brains of these young visitors.

Let us continue to use art in all its forms to take critical conversations about race, equity, justice and understanding forward with us as we move into a new presidency, a new generation and even a new semester. We must never forget how to “picture the dream,” as the exhibition title encourages us to do, striving for equity in each of our daily actions and beliefs.

Zimra Chickering (24C) is a born and raised Chicagoan who studies art history and nutrition science. She is also a student docent for the Michael C. Carlos Museum, Woodruff JEDI Fellow, educational committee chair for Slow Food Emory, and Xocolatl: Small Batch Chocolate employee. Zimra loves cooking, visiting art museums, photography, doing Muay Thai, drinking coffee, and grocery shopping. She uses writing as an outlet to reflect upon issues and oppurtunities within artistic institutions, and the unique ways in which food and art can act as communicators of culture.