Without even a football team, I think I can make the polemic assumption that many of us here at Emory are less than interested in sports.

Then again, the argument can be made, I suppose, that we venerate sports to such an elevation as to intentionally keep our athletes away from them.

We in Kazakhstan, however, are never faced with such dispassion about our sports. This is because Kazakh sports are vastly superior to those of the American variety. Therefore I urge you, dear reader, to wipe the American misconception of the term “sport” from your memory and embrace the beauty of our athletic heritage.

As a child in Uzbekistan, I remember trying to introduce the neighborhood kids to baseball.

After several run-throughs, the questions were always the same: “Can I defend myself with the bat after I hit the ball? Do I have to run the bases in order?” Then they’d run the bases backwards, trip the runners and, this time true to the sport, blatantly lie about fouls, balls and strikes. These were, of course, all after the initial shock of baseball’s primary tenets: “you hit a ball with a stick and run in circles?” My backyard quickly devolved into memories from Little League. I soon realized that it was useless to bring America to them, and, in true accordance with everything American, that there was no foreign oil to merit further frustrations. And so, we all decided to play a local variant of hide-and-go-seek-tag instead.

Later, in Kazakhstan, I began to realize the rich athletic heritage of the person I was becoming.

My first summer there I joined a baseball team, the initiative of the American Embassy sponsored by Exxon Mobile. When the few local kids, my brother and I all gathered for practice in Centralni Stadion, Central Stadium, I began to watch, to see what sports the Kazakhs engaged in. It was the perfect situation for a field study: multiple small soccer fields, a running track, a long jump pit, acrobatic bars, a baseball field, a discus-throwing field and more had somehow been all lumped into one multipurpose sports field hardly bigger than an American high school football field.

Although disconcerted by the discus throwers, who practiced right beside the baseball field with notorious aim, I was enchanted by the legions of boxers, sweating out their rigorous routines and stretches and the gymnasts, lithe on the bars.

The soccer players, twisting, wriggling, juggling the soccer ball in their confined spaces, held me spellbound as an outfielder.

The occasional javelin thrower certainly sharpened my peripheral vision and was no doubt, in conjunction with the discus throwers, the reason for my superb spatial relations scores in general aptitude testing.

On the slopes of the Tien Shan mountains I encountered world-class skiers and a few snowboarders.

Kazakhstan was also the proud host of the 2012 Winter Olympics and has fine teams in cross-country skiing, cycling, football (actual football, not American), ice hockey, speed skating and even bandy. In Olympics in general, Kazakhstan has not escaped the world unnoticed, taking medals in boxing, weight-lifting and most noticeably, cycling. Cycling is probably Kazakhstan’s most successful field of athletics, with a few top five Tour de France finishes. The citizens of my hometown, Almaty, know that the Mongolian passion for horses, now diverted to the twin spinning wheels of bicycles, runs deep among the Kazakh people; it is not uncommon for hordes of them to clog up the roads and back up traffic.

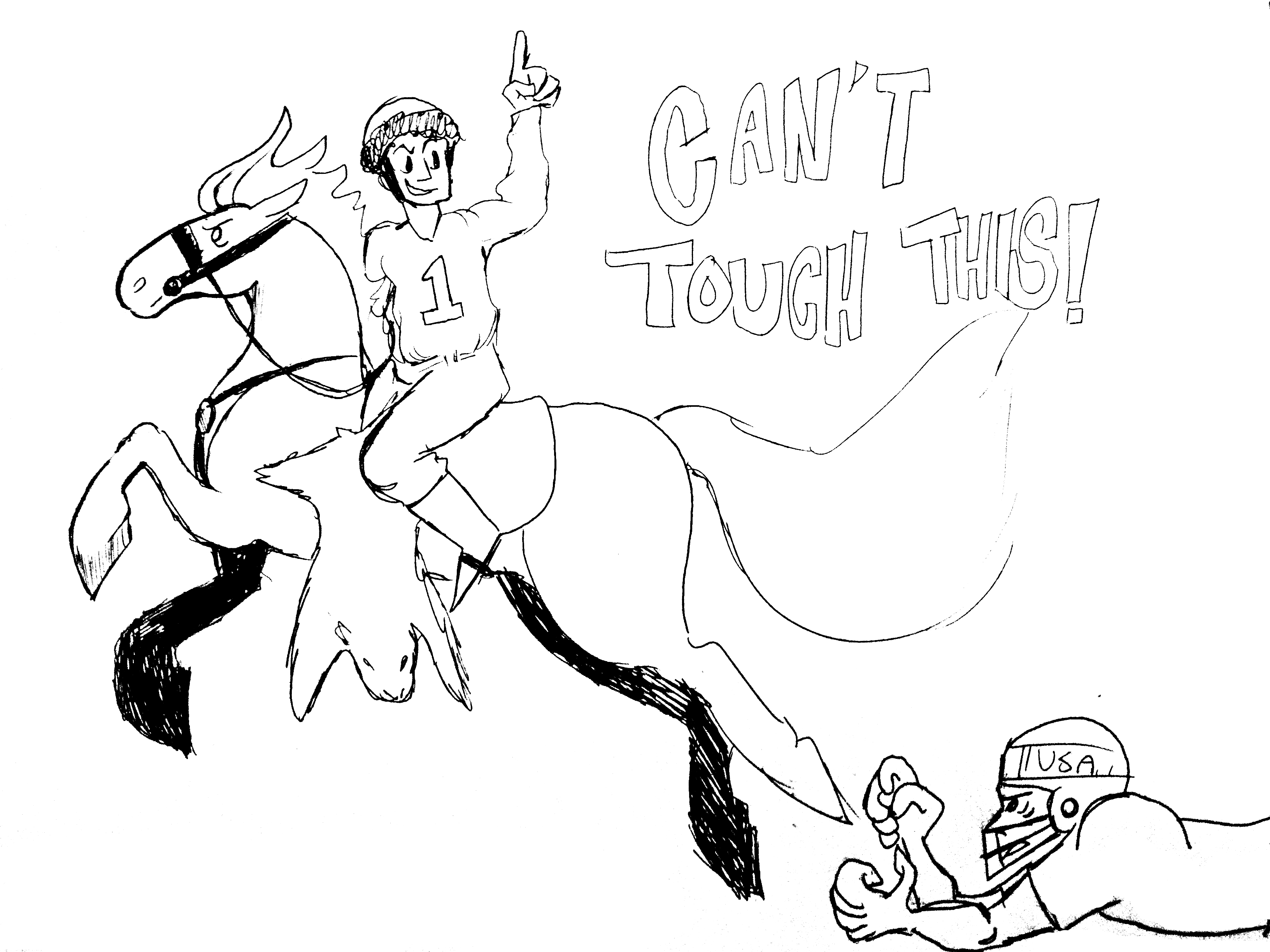

Of course, no discussion of Kazakhstan’s athletic pastimes is complete without Kokpar. Imagine, dear reader, a mash of horse and rider as the sharp hooves dig into a sheep carcass, the center of the commotion. Riders pluck up the courage to duck into the thick of it, hanging by their stirrups, retrieving the hundreds of pounds worth of carcass and trying to haul it to the end of a field to score a goal. All the while the carrier faces opponents’ horse whips, horse rammings and grabbing hands. Games can last days. Unsurprisingly, the results can be fatal.

Negotiations with Wagner and the Emory Equestrian club to start a Kokpar team are still in progress.

Jonathan Warkentine is a College sophomore from Almaty, Kazakhstan.

Illustration by Mariana Hernandez

The Emory Wheel was founded in 1919 and is currently the only independent, student-run newspaper of Emory University. The Wheel publishes weekly on Wednesdays during the academic year, except during University holidays and scheduled publication intermissions.

The Wheel is financially and editorially independent from the University. All of its content is generated by the Wheel’s more than 100 student staff members and contributing writers, and its printing costs are covered by profits from self-generated advertising sales.

congratulations for the beautiful text

como reconquistar http://www.outrachance.com.br/

not if they genuinely dont treatment about our survival which they dont it could be bullshit but when it does come about it could likely be somthing similar to this . NO warning by any means, thats why all the main governments in the globe are actually making underground bunkers which possibly want do the job anyway