Emory University Police Department (EPD) officer Randall Terry, Jr. and officer Alexander Mawson (08C) saved an allegedly depressed man who was thinking of committing suicide on a night shift last year, Tarry said. When Mawson arrived on the scene, the person was at the top level of a parking garage facility, dangling his legs off the ledge. They spoke to him about why he wanted to end his life and appealed to his sensibilities.

“I’ve seen the victims of highway accidents, medically unstable students and dead bodies, but that was always after the fact,” Terry said. “This would have been an entirely new trauma.”

Although a typical EPD night does not often involve events as extreme as deterring a suicide, The Emory Wheel shadowed Mawson between 9 and 11 p.m. Friday, Nov. 11, to get a closer look into the life of an officer on a night shift. I sat in the shotgun of a white and blue EPD car as Mawson pointed out violations: a driver drove through a stop sign and a fraternity left a beer can out in its front lawn. I hadn’t paid much attention to either, but his trained eye did. All EPD officers receive the same training as DeKalb County Police Department officers, according to Mawson. EPD officers can respond to dispatch calls that range from providing backup to Emergency Medical Services (EMS) to checking suspicious activity. Besides taking calls, their responsibility is to patrol campus and to conduct building and location checks.

Mawson’s patrol car houses minimal technology. An old fashioned radio picks up DeKalb County’s transmission. Mawson said it’s helpful to keep an ear on what’s happening around campus. Additionally, he writes citations and records meaningful evidence of ongoing investigations on his laptop. Strapped to his waist, Mawson carries a pair of handcuffs, a flashlight, a bottle of pepper spray, an adjustable baton and a firearm. At 9:15 p.m., we walked through Sanford S. Atwood Chemistry Center to check for unusual activity and building maintenance. Instead of switching on the lights, Mawson turned on his flashlight to guide us through the corridors and a chemistry lab. Immediately, we were hit with a vinegar smell and heard a machine pumping.

“You can see the sign there that says the strange smell is normal,” Mawson said.

We kept walking. The building check was complete.

“It’s usually preventative,” Mawson said. “You’re going in to look for someone in the building who is not supposed to be there. Is there a door pried open or propped open?”

Our next stop was the Candler Mansion on Emory’s Briarcliff campus. The abandoned historical landmark is a frequent place for students to go ghost hunting or host social events. However, many do not realize that going inside is a crime, Mawson noted. At 9:45 p.m., his walkie-talkie buzzed louder than usual. A college student staying in LongStreet-Means Hall had called EMS. Mawson was called to provide backup. Ambulance and firetruck sirens whirred as we pulled up to the freshman housing complex. Due to confidentiality, I waited in the lobby for Mawson to complete his duties.

“Our job is really to document what’s going on, document what we saw and to observe,” Mawson said. “So we’re asking questions, finding out who the person is, but we’re not taking any punitive action.”

This procedure applies not only to medical situations, but also to calls regarding suspicious activity and parties, according to Mawson.

“The other thing to keep in mind, too, is that Emory is an open campus,” Mawson said. “You just have to be aware that anyone on campus may not be a part of the community. We are very mindful of respecting people and people’s privacy.”

Mawson said that the EPD sometimes receives calls about suspicious activity. One time, Mawson observed a stranger who was whispering to himself and pacing up and down a sidewalk. As he got closer, Mawson realized that the man was talking to someone through his Bluetooth earpiece.

“It’s our job to go find out [if there is actual danger or not],” Mawson said. “Someone felt concerned enough to call us. We have to go and investigate.”

At school-registered parties, EPD officers lay low. They want to encourage good community relations between officers and students who abide by the law.

“[We try to just] be on the perimeter of the party,” Mawson said. “[We] keep people who are not supposed to be there out. We don’t walk through the crowd.”

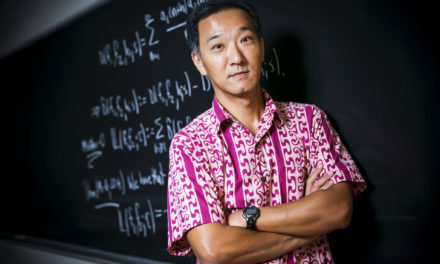

According to Mawson, EPD on-campus officers will begin wearing body cameras to increase transparency between the police force and individuals. Also, the EPD is in the process of strengthening their social media presence via Facebook and Twitter. Before working for the EPD, Mawson served as a DeKalb County police officer and detective from 2008 to 2014. But his initial interest sprouted when he was hired to work for the Police Cadet, a work-study job at Emory. His career goal is to work for a federal law enforcement agency such as the FBI. Since then, Mawson has worked the night shift from 7 p.m. to 7 a.m.

According to Mawson, helping the community in any way possible is his first priority, even if it means working odd hours. Besides calling 911, blue-light emergency phones, located at street corners around campus, enable students to alert the EPD during precarious situations. College freshman Will Bashur says he feels safe walking back to his dorm late at night, or going for a jog when it’s dark outside. He also says that the police authorities are respectful of him and other students on campus.

“They definitely establish their authority. I’m not like, oh wow I can mess with these guys,” Bashur said. “They are not rough individuals. I’ve never felt fearful of them, which is a good thing. It’s the perfect balance.”

Varun Gupta (20C) is studying political science and philosophy. He seeks discomfort by shadowing people in different professions, such as campus security, a sous chef and bar manager. Apart from the Wheel, you can catch him playing ultimate frisbee or recounting a crazy travel experience from one of 21 different countries that he has visited.