The largest collection of works by Frida Kahlo and Diego Rivera to be exhibited together opened last Thursday at the High Museum of Art. The exhibition, titled “Frida & Diego: Passion, Politics, and Painting,” features 140 paintings, drawings and lithographs by the couple, as well as 44 personal photographs. Valentine’s Day was an appropriate date for this exhibition to open, considering the turbulent romance between the two artists, which involved a marriage, divorce and subsequent remarriage.

Rivera, arguably the most notable Mexican artist of his day, was 21 years his wife’s senior and received formal training as a painter in Europe in the early 20th century. Kahlo, however, was born three years before the Mexican Revolution – which Rivera only experienced as a young man abroad – and was entirely self-taught. As the exhibition’s title suggests, both artists were profoundly influenced by politics, especially the Mexican Revolution and Marxism.

Despite this shared sensibility, the influence of politics played out in drastically different ways in each artist’s work. After going through a Cubist period primarily influenced by Picasso, Rivera turned to the medium that would make him a global star of the art world: the mural. For Rivera, murals were an opportunity to move fine art out of museums and the academy and return them to the people, as well as an opportunity to make the common laborer a subject worthy of artistic attention. Though Rivera’s early Cubist paintings are on display at the High, replicas of his murals – most of which still grace the walls of cities such as Mexico City and Detroit – are printed on the museum’s walls. One of his most famous murals, 1928’s The Arsenal, features Frida at its center.

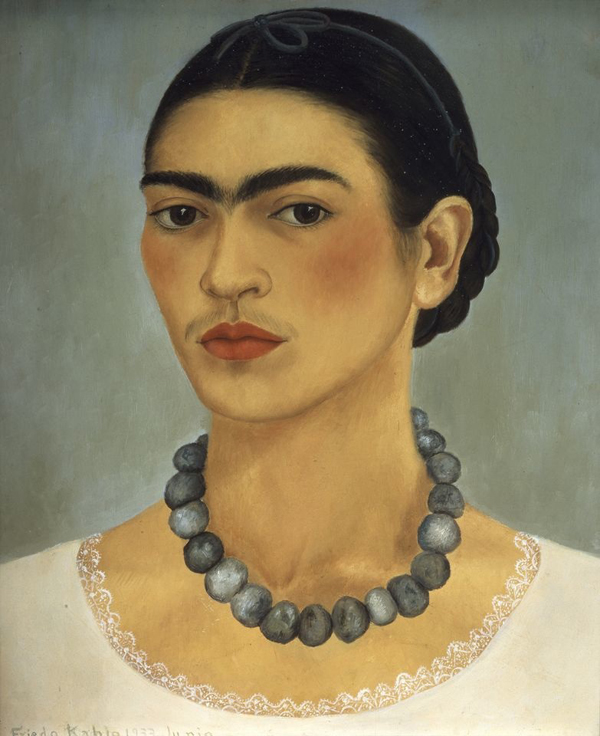

Where Rivera sought to display his politics in the public sphere, Kahlo explored her political sympathies in much more private, intimate ways. A prime example of this is the Soviet hammer and sickle she painted over her heart on the plaster cast that she was forced to wear after one of the numerous surgeries she underwent over the course of her life. Frida’s personal life and professional career contrast starkly with those of her husband. While he received formal education and international acclaim, she taught herself to paint and remained largely unknown outside of her circle of friends until after her death. She once famously said, “I paint self portraits because I am so often alone, because I am the person I know best.”

The exhibition pays particular attention to the physical limitations and lifelong pain Frida suffered after a horrific streetcar accident in her late teens. She is quoted as saying, “I suffered two great accidents in my life. One in which a streetcar knocked me down. The other accident is Diego.”

The photographs of the couple at the conclusion of the exhibition reveal the remarkable place they occupied in 20th-century Mexican culture. Hungarian-born American photographer Nickolas Muray’s vibrantly colorful photos of Frida show her commitment to traditional Mexican attire, as well as her distinctly modern demeanor. Between the two of them, Kahlo and Rivera bridge the ancient and modern, the public and private, the personal and the political.

One of the exhibition’s strengths is the way it includes quotes from the couple, which are printed in both English and Spanish along the museum’s walls. The text that accompanies each work is also printed bilingually. One such quote, featured in the first room of the exhibition, recalls Kahlo saying, “Diego is not anybody’s husband and never will be, but he is a great comrade.”

The couple’s struggle to redefine their political and private lives is beautifully communicated through the exhibition. One gains a sense not only of Kahlo and Rivera’s respective artistic oeuvres, but of their lives, together and apart.

Despite the significant difficulties Kahlo and Rivera faced as a couple, which included multiple failed attempts to have children and Rivera’s affair with Kahlo’s sister, their devotion to one another is apparent in their artistic work and in the photographs of them. Near the end of the exhibition there is a quote from an interview with Frida where she calls Diego “my child, my son, my mother, my father, my husband, my everything.”

“Frida & Diego: Passion, Politics, and Painting” will run until May 12 at the High Museum, which is the only American venue to host the exhibition. Special events related to the exhibition include a film series and events for children. Screenings of the 2002 film “Frida” will be presented each Saturday until May 11 at 2 p.m. Admission to the screenings are free with museum admission. The High Museum will host College Night on Feb. 23, which includes a tour of the exhibition, a dance performance and salsa and tango lessons. Admission is $7 for students.

– By Logan Lockner

The Emory Wheel was founded in 1919 and is currently the only independent, student-run newspaper of Emory University. The Wheel publishes weekly on Wednesdays during the academic year, except during University holidays and scheduled publication intermissions.

The Wheel is financially and editorially independent from the University. All of its content is generated by the Wheel’s more than 100 student staff members and contributing writers, and its printing costs are covered by profits from self-generated advertising sales.