Courtesy of the Rose Library

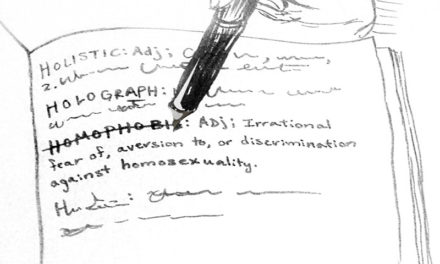

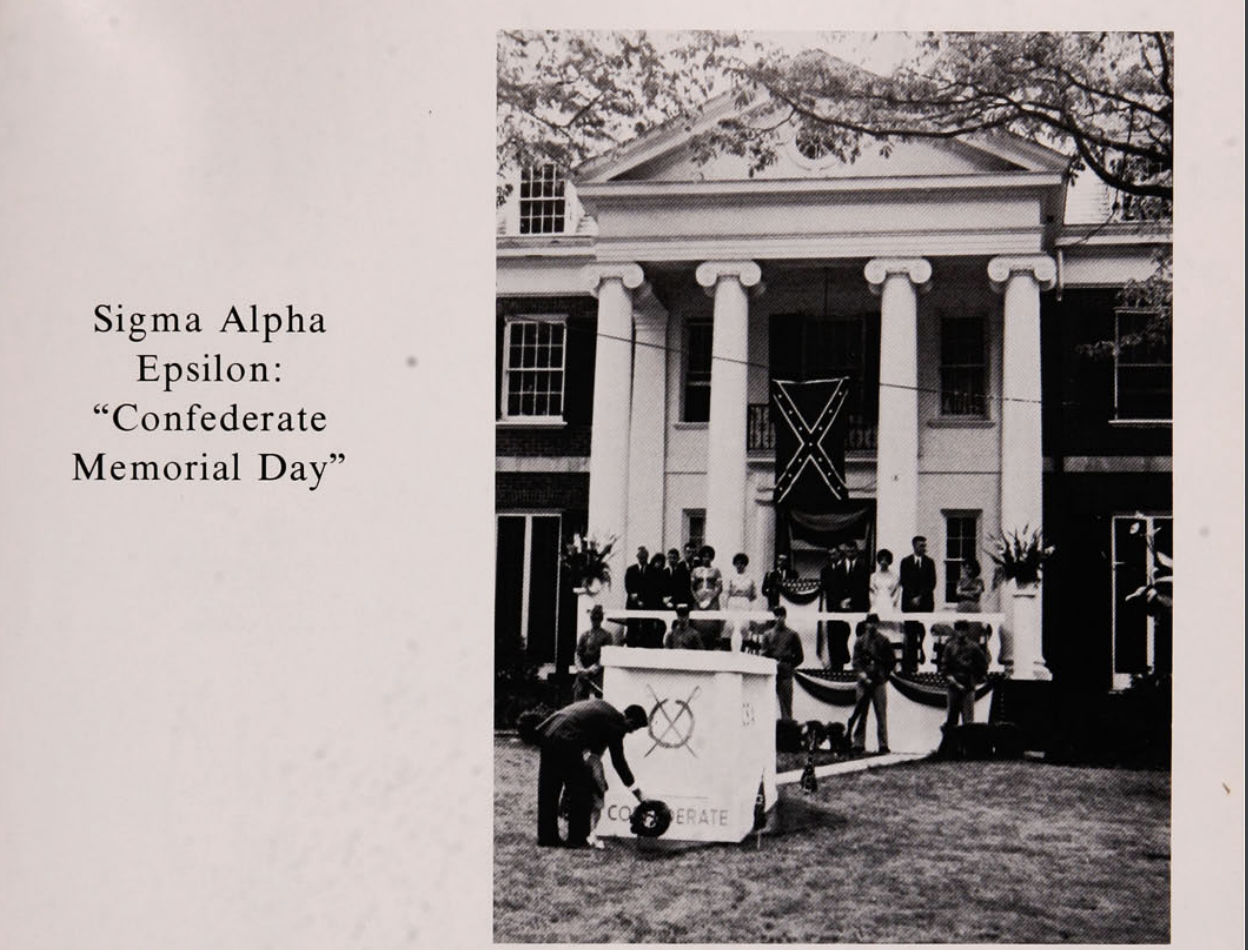

It’s difficult to hide from history, as Virginia’s top politicians have recently learned. In light of this controversy, University President Claire E. Sterk recently addressed remnants of Emory’s racist past. This troubling history includes yearbook photos from throughout the 20th century that feature students boasting Confederate symbols, wearing blackface, impersonating Native Americans and wearing Nazi and Ku Klux Klan costumes. In a Feb. 20 statement, Sterk wrote that Emory will establish a Legacy Commission to better confront the legacy of racism that taints our school’s history.

The commission, meant to investigate how Emory has grappled with racial and ethnic discrimination in its past, is a move toward addressing these incidents. The University should be commended for its initiative and accountability, but lip service is not enough. In the University-wide announcement, Sterk does not provide a definitive plan for the commission’s function. Emory should look to other universities that have begun initiatives to address similar issues.

Universities including Harvard University and Columbia University have already launched probes into their tangled history with slavery. Harvard’s 2016 research findings were publicly displayed in the Pusey House Library and can be accessed online. Under the tutelage of Eric Foner, a Pulitzer-prize winning history professor at Columbia, students researched and published Columbia’s links to slavery. The university offers the course “Columbia University and Slavery” today.

More recently, Duke University and the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill have removed or planned to relocate Confederate monuments, while also creating educational resources about their school’s controversial histories.

Of the schools that have begun reckoning with their racist pasts, Georgetown University has engineered the largest and most sweeping effort. The university created the Georgetown Memory Project in 2016 to tell the story of 272 slaves who were sold by the college in 1883. Georgetown now offers free tuition to any descendants of those 272 slaves and has made a concerted effort to engage the “Descendent Community” in its reparation plans.

Other schools’ situations are not identical to Emory’s, but they still serve as a model for how the University can deal with its history. While Emory did not directly own slaves, it did employ slave labor. Moreover, most early faculty, trustees and every antebellum president owned slaves, and much of the money used to found the College came from slave-owning individuals.

Emory’s Legacy Commission could begin addressing the disturbing details of Emory’s conception by creating and distributing physical markers or plaques that offer historical information about the namesakes of Emory buildings, many of whom owned slaves. These memorials should include all aspects of their history — not just those that portray them favorably.

The commission should also consider recommending that Emory rename halls and memorials named for those with unsavory legacies. Longstreet-Means Hall’s namesake, Augustus Baldwin Longstreet, was a passionate defender of the Confederacy, slavery and the Old South. He also served as president of Emory University from 1840 to 1848. During his tenure, he published “A Voice from the South,” which attempts to justify slavery and criticizes northern states for profiting from the slave trade. Longstreet-Means Hall, the first-year residence hall, may be a great place to live, but its namesake is not a sound representative of Emory’s modern values. Instead of naming buildings after Confederate alumni, the University could use the names of alumni who contributed to its racial integration, such as Delores P. Aldridge, the first African American to hold a tenure-track position on campus.

The administration is not the only body responsible for addressing the University’s past.

Most of the racist photos in the archives depict fraternity activities; five chapters represented in these images are still on campus. Emory’s Interfraternity Council (IFC) should issue statements addressing these racist images and make clear that discriminatory behavior will not be tolerated. These photos provide fraternities an opportunity to speak out against the sentiments expressed therein; to waste such a moment would be folly, aligning Greek life at Emory with the reputation for racism popularly associated with fraternities.

Commission members must be bold. While other universities have taken strides to manifest their involvement with slavery, segregation and racism, Emory’s past efforts have been comparatively discreet. Sterk has laid a strong foundation for reconciliation efforts by founding the legacy commission. This group has the ability to reshape the way Emory understands its past, and change the way our community thinks and talks about race.

As recently as 1992, Emory students wore Confederate uniforms for a photo shoot and the University is still working to address the black student demands presented in 2015. Our work is not done.

If Emory aims to be a progressive institution, Sterk’s Legacy Commission must educate the Emory community about the University’s less progressive history.

The Editorial Board is composed of Zach Ball, Jacob Busch, Ryan Fan, Andrew Kliewer, Madeline Lutwyche, Boris Niyonzima, Omar Obregon-Cuebas, Shreya Pabbaraju, Isaiah Sirois, Madison Stephens and Kimia Tabatabaei.

The Editorial Board is the official voice of the Emory Wheel and is editorially separate from the Wheel's board of editors.