When Julianna Chen (23C) first saw that six East Asian women had been killed by a white man across three Atlanta-area spas on March 16, she felt “numb.”

Like many around the country, Chen had seen a spike in hate crimes against Asian Americans reach national media over the past several weeks, as images of elderly Asian individuals being pushed down or beaten in cities from Oakland, California, to New York City flooded her social media feed.

But she didn’t think it would happen so close to her — she lives just a few miles from Aromatherapy Spa and Gold Spa, two of the shooting locations.

“I envisioned a lot of my own death, and that did horrible things for my mental health,” Chen said of the days following the attacks, as information about the victims was released and the pain sunk in. “I recognize the chances of actually being shot are very slim, but I’m not going to not think about that.”

Police statements, family members and acquaintances of Aaron Long, the shooter, have indicated that Long’s “sex addiction” contributed to the murders. In days following the deaths, representatives from the Federal Bureau of Investigation and local police forces said the attacks did not appear to be “racially motivated,” with one officer stating that Long “had a really bad day.”

Emory Asian American students and faculty, however, believe that ignoring race as a factor working in tandem with sex and class only further harms Asian communities, given that the shootings occurred at three Asian businesses.

“People have been talking about this for years, and there have been multiple cases of anti-Asian racism dating back to when Asian Americans first started immigrating to the U.S.,” said Jane Wang (22C), co-chief of staff for the Emory Asian Pacific Islander and Desi American Activists (APIDAA). “It's really frustrating to not see our issues pushed to the forefront until people are getting killed.”

The U.S. has a history of mistreating Asian women

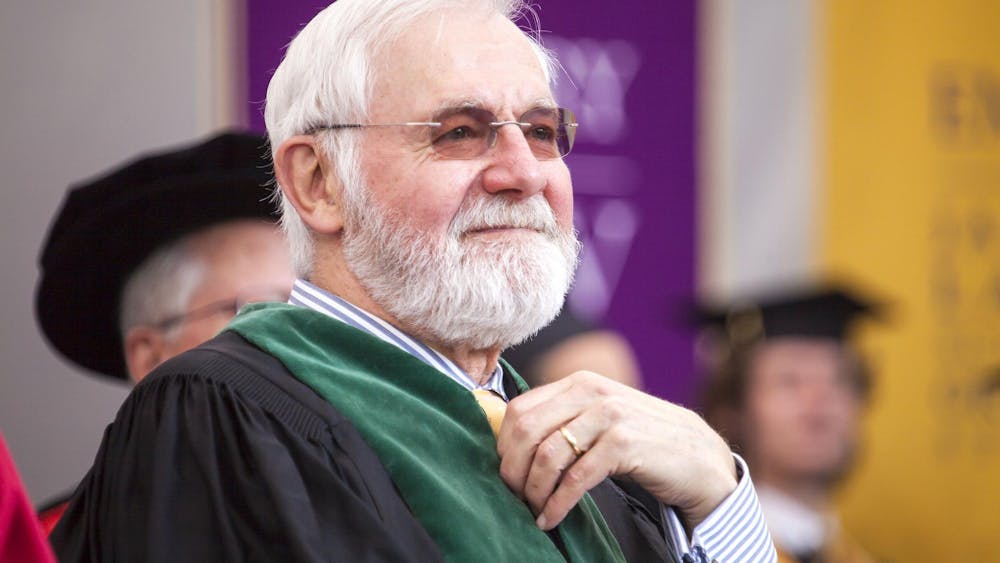

Violence against Asian Americans isn’t new. From internment of Japanese Americans in the 1940s to Vincent Chin’s murder in 1982 to the spike in hate crimes against South Asians after 9/11, it’s all-too-common, said Assistant Professor of History Chris Suh, who specializes in Asian American history.

This harm can manifest differently against Asian women. The U.S.’ history of hypersexualizing and fetishizing East and Southeast Asian women dates back over a century to the Page Act of 1875, a law that prevented Chinese women from coming to the U.S. unless they could prove they weren’t prostitutes.

Throughout World War II, U.S. soldiers occupying East and Southeast Asian countries were often provided with women for sex work purposes, Suh noted. The War Brides Act in 1945 was put in place specifically to allow women — primarily Asian women — who married American soldiers to come to the U.S. legally.

American popular culture also exoticized Asian women, ranging from movies starring Anna Mae Wong in the early 20th century to the popular 1989 musical Miss Saigon. Media that portrays Asian women as submissive or hypersexual persists to this day.

Views of East and Southeast Asian women in the U.S today are influenced by these historical factors coming together, Suh explained.

“It has a legal dimension, it has a military dimension but it also has a cultural dimension, and I do think that all three really shape the way we—and when I say we, I'm thinking about Asian Americans themselves as well—think about Asian women,” Suh said.

This phenomenon is experienced by numerous Asian American women at Emory, including Stephanie Zhang (22C), co-chief of staff for APIDAA.

“As an Asian American woman, I'm so used to my identity being hypersexualized and fetishized,” Zhang said.

“The shootings that happened to these women is literally every woman of color’s worst nightmare, but it's always expected. At the end of the day, the best thing that could happen to us is somebody catcalls us on the street but the worst thing that happens to us is that we're gunned down because of some guy who has a weird violent fetish or thinks of us as objects ready to be shot.”

Chen expressed similar sentiments, saying, “Asian women, including myself, will sometimes be approached, and people will assume that they are more promiscuous than they actually are. … It really changes how you perceive yourself.”

How stereotypes suppress Asian American voices

As discussions about race and being a minority in this country have become mainstream in recent years, Asian Americans have often been excluded from the narrative.

This is in large part due to the model minority myth. The concept, founded in the late 20th century, positions being Asian as proximate to whiteness. Asian people are thus associated with having more privilege and being predominantly well-educated and wealthy—assumptions that often enable racism to go unchecked.

“The model minority myth, as well as class bias, has really shaped the lives of these people, not only the people who are murdered but the people who survived too,” Suh said. “It's really tragic that Asian Americans are often seen as this monolithic success story, when in fact, it's so easy to prove that that's not true.”

The myth operates under the belief that Asian people are a homogenous group when in reality, the subcategories under the broadly-defined race consist of people with different cultures and phenotypical appearances. As such, these subgroups face varying experiences in areas like academics and employment.

Differences are exemplified in the wage gap among Asian American and Pacific Islander (AAPI) women. A March 2021 report from the National Partnership for Women & Families showed that the pay of an AAPI woman ranges on average from $0.52, received by Burmese women, to $1.21, received by Indian women, compared to $1 a white, non-Hispanic man receives.

Additionally, while the poverty rate for Asian American households is 6.5% on average, 35% of Burmese people and nearly 30% of Hmong people in the U.S. live in poverty.

The COVID-19 pandemic has only exacerbated violence and discrimination against Asian people in the U.S., as China has been villainized as the cause of the pandemic and those with phenotypically-East or Southeast Asian features have become scapegoats.

The Stop AAPI Hate reporting center received 3,795 hate crime reports from March 19, 2020, the pandemic’s early stages, through Feb. 28, 2021. Of those incidents, women reported crimes 2.3 times more than men.

Asian Americans were more likely to report negative experiences because of their race or ethnicity since the COVID-19 outbreak, a June 2020 Pew Research study showed.

Wang recalled an instance when she brought kimchi fried rice onto an Emory shuttle bus, only to receive negative remarks from the shuttle driver who questioned what “other weird foods” she ate and commented that China caused COVID-19 because of “unsanitary conditions.”

“I was like, that doesn't seem right, but it's like, you're on a shuttle, what am I going to change on the seven-minute ride back to main campus?” she said.

Stereotypes about East and Southeast Asian countries have only contributed to anti-Asian sentiments. Phrases like the “Chinavirus” and the “Kung Flu” perpetuated by political leaders have directly linked the disease with Asian countries, which Zhang noted is not a historical anomaly.

“People are so ready to blame Asian communities and accept this narrative of Asian Americans being diseased that we're essentially just rehashing narratives that have come up before,” Zhang said.

Solving these issues starts with acknowledgment and education

Moving forward from this tragedy is an uphill battle. Because Asian American history and struggles are rarely covered in school curriculums or popular culture, Suh said that achieving racial parity needs to start with basic steps: acknowledging that Asian people in the U.S. face racism.

“In order for there to be change, we need to recognize the problem first,” Suh said. “Events like these really heighten that actually no, there are problems that Asian Americans face, and some of them are actually similar to what other major marginalized communities face.”

Still, despite increased media attention, many are hesitant to believe that real change will come after years of Asian American struggles being sidelined.

“With so many of these things, people are mobilized on social media for a week, they're sharing their stories and then the next week, you're back to your regular lives,” Wang said. “Except for some of us, our regular lives are just this, just hearing about anti-Asian violence.”

Suh echoed her thoughts, saying, “With decades of violence, it's just like, when will we ever change? It seems like it's the same over and over and over again. I'm exhausted.”

Despite reservations, Emory students believe education is the key to beginning to dismantle anti-Asian hate. Groups like Asian Americans Advancing Justice and the Asian American Journalists Association work to provide mental health relief for Asian individuals and educational resources for those who wish to stand with the community.

At Emory, APIDAA has organized fundraisers for women’s groups and advertised therapy events for hurting Asian students who have become “hypervisible,” Wang said.

In coping with mental effects of the attacks, Chen took to Instagram and Twitter to voice her thoughts about the fetishization of East and Southeast Asian women, discuss the intersection of class with race and sex and promote a personal fundraiser for Red Canary Song, a “grassroots massage parlor worker coalition.”

She’s since raised over $1,000 from peers that she plans to split between three organizations across the country supporting Asian women and destigmatizing sex work. However, she says true change won’t occur without allyship from those outside the Asian American community.

“Ultimately, I think white people have to come to terms with the fact that they are the problem,” Chen said. “I cannot think of a different way to say this: We should not be asking Asian Americans to have to fix the problem of which they are the victims.”