Last year, Indiana Governor Mike Pence signed the Religious Freedom Restoration Act, permitting private business owners to discriminate against potential customers if the discrimination is justified by religious beliefs, including “traditional family” views practiced in many Christian denominations. Critics of this bill believed it would target discrimination against the LGBT community, yet despite an extraordinary level of opposition at both the domestic and national level, Pence signed the law.

The result?

Boycotts costing the state that bills itself as “The Crossroads of America” an estimated eight figures worth of damage and $60 million loss in tourist revenue. Consequences of the bill extended beyond tourism into the private sector. Chief Executive Officer of Salesforce Marc Benioff announced that he was “canceling all programs that require our customers/employees to travel to Indiana to face discrimination” once Pence signed the bill.

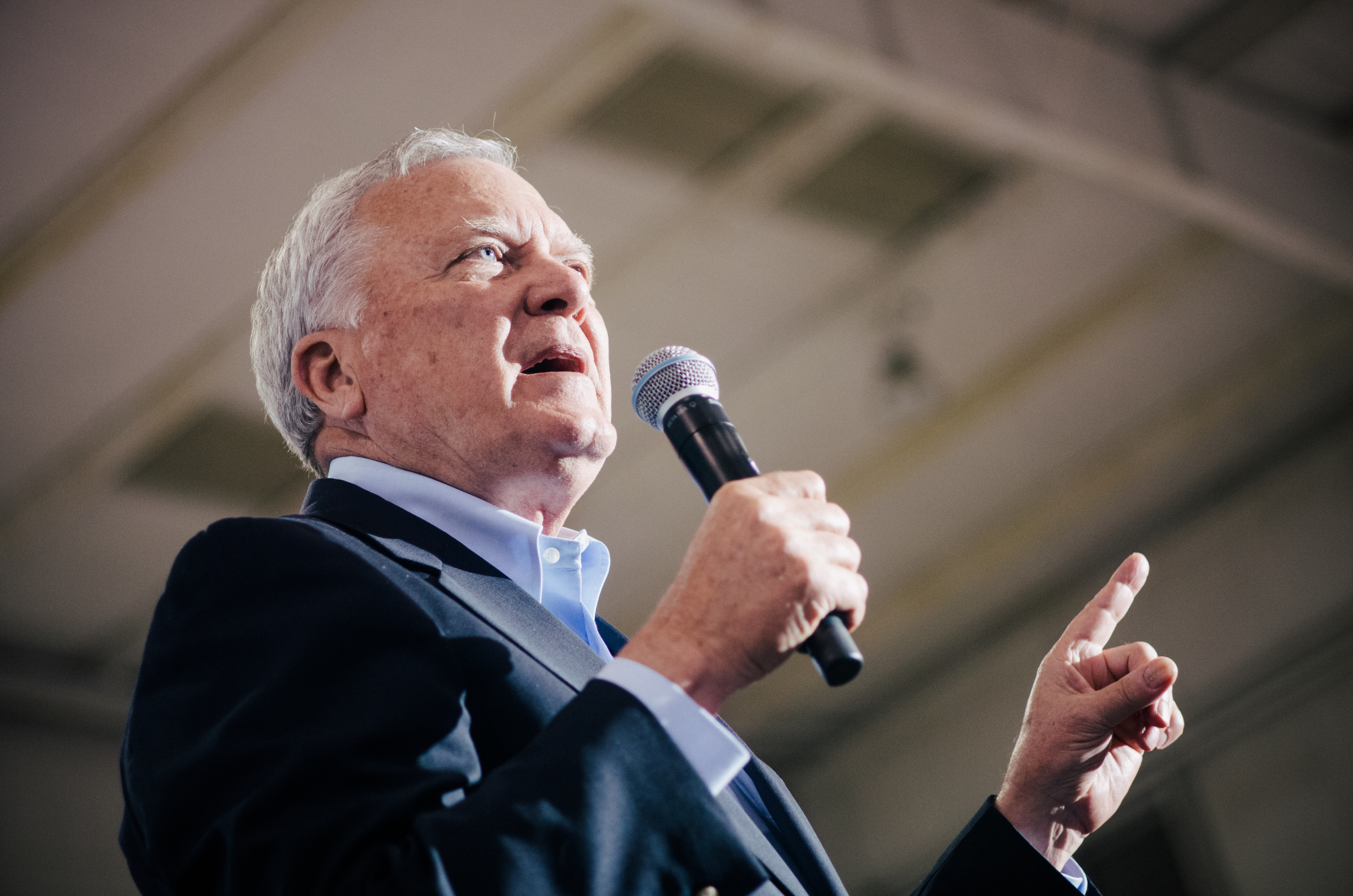

This week, Georgia Governor Nathan Deal was faced with a decision similar to the one Pence had to make. According to Emory Professor of Law Timothy Holbrook, the Georgia “religious freedom” bill, House Bill 757, was considered to be even more extreme than the Indiana version, with its provisions extended to some taxpayer-funded organizations.

Despite the bill’s easy passage in the state legislature, Deal vetoed the bill, scoring a win not only for the Georgia LGBT community, but also for those in favor of the maintenance and growth of a strong economy. Regardless of the diverging social stances held by Democrats and Republicans, both parties agree there’s a need to preserve the economy. The veto transcended partisanship and saved the Georgia economy.

Countless businesses and organizations such as Salesforce, Apple and Wal-Mart threatened drastic actions that would devastate Georgia’s economy if Deal signed the bill into law. The National Football League (NFL) and the National Collegiate Athletic Association (NCAA) planned to exclude Atlanta as a possible host city for the Super Bowl and potential championship games, respectively, potentially costing the city of Atlanta and the state of Georgia drastic losses in jobs, wealth and economic prosperity.

Emory would have been affected directly by Deal signing the bill into law. With a state-sanctioned tax break awarded to film companies, Atlanta sites, including the Emory campus, have been used frequently as sets for film productions. Two weeks ago, a pilot episode for “The Jury” was filmed outside Candler Library. A movie about Dorot Professor of Modern Jewish History and Holocaust Studies Deborah Lipstadt was filmed on campus. In the fall, White Hall was used in a scene for a new movie starring Chris Evans. Several Hollywood corporations, including Disney and Warner Brothers, two of the largest film companies in the country, expressed opposition to House Bill 757, signaling intentions to cease production in Atlanta, a decision which would have taken away both revenue and big-screen exposure for Emory.

Thankfully, Deal dodged these scenarios with the veto and avoided repeating the mistake made by Pence. It would simply be irresponsible of any elected official to induce an economic drought. While supporters of House Bill 757 assign incredible value to the freedoms that religious groups should be allowed to exercise, the potential devastation caused by extending more “religious freedoms” cannot be ignored.

Analogous to freedom of speech, freedom of religion is not necessarily absolute in the United States. The 1919 United States Supreme Court case Schenck v. United States did not extend the Constitution’s First Amendment to the defendant, who tried to instigate chaos at an Army draft board. In the proverbial case of shouting fire in a movie theater, freedom of speech no longer exists.

Similarly, the First Amendment permits the exercise of religion, but vetoing a bill that permits discrimination justified by religious beliefs can be rationalized. This becomes doubly easy when faced with economic backlash.

This assured economic drought that would have resulted from Deal signing House Bill 757 exemplifies the influence the private sector can hold over the government. Often seen as “corrupt behavior,” discussion of the private sector’s influence over government is frequently paired with choice swears. Yet when a business or organization may potentially experience a negative backlash for conducting operations in a discrimination-riddled area, voicing discontent and threatening to punish the economy is a necessary course of action. In the case of House Bill 757, such action was effective.

The opportunity to learn from others’ mistakes is not readily available. Learning from the consequences faced by the state of Indiana and lending an ear to the private sector makes Deal’s veto an incredibly commendable decision. The veto not only protects members of the LGBT community from discrimination in a majority conservative Christian state, it maintains Atlanta’s designation as one of the strongest cities in the Southern economy.

Brian Taggett is a College freshman from Kalamazoo, MI

brian.andrew.taggett@emory.edu | Brian Taggett (19C) is from Kalamazoo, Mich., majoring in political science and Latin American and Caribbean studies. He served most recently as editorial page editor. Between referring to carbonated beverages as "pop" and unabashedly cheering for the Detroit Tigers and Red Wings, Brian is about as Michigan as they come.

If the choice is between 1) religious freedom wherein my nine-year-old daughter using the bathroom without worry of men poking their heads into her stall and 2) experimental patronage to gender-confused youths whereupon we get the 53rd Superbowl, I choose religious freedom.

You can have your superbowl somewhere else where there aren’t fathers who care about, among other things, bathroom privacy.