A decade ago, Emory neurologist and doctor Lynn Marie Trotti made an accidental discovery when one of her patients was prescribed the antibiotic clarithromycin for an infection. After taking the medication, the patient’s hypersomnia, a little-understood condition which causes severe daytime sleepiness, vanished.

“She called me up and said, ‘It’s amazing, I can’t sleep at all,’” said Trotti, who specializes in the treatment of sleep disorders. The clarithromycin had caused the patient to develop insomnia for the first time in years, giving her hope.

This discovery was the break that Trotti and her colleagues at the Emory Sleep Center had been hoping for. Trotti’s patients with hypersomnia were so tired that they could no longer accomplish minor daily tasks, and the few drugs available for the condition did not work for many of them.

Since then, Trotti and her colleagues have prescribed clarithromycin in cases where other options have failed.

“What makes me passionate about this research is all the people I meet in my clinic that need this research,” Trotti said.

In 2010, Trotti applied for a grant to conduct more formal research on clarithromycin’s effects. After her 2015 clinical trial provided additional evidence that the drug worked to reduce the effects of hypersomnia, the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke awarded Trotti a five-year $2.1 million grantto continue research.

Trotti’s study is currently recruiting test subjects, and is expected to be completed in July 2024.

The upcoming clinicaltrial will explore whether clarithromycin’s antibiotic effects could decrease daytime sleepiness by reducing inflammation and harmful bacteria.

The trial will also attempt to replicate previous 2017 research that found that clarithromycin reduced the activity of GABA receptors in cultured neurons. GABA receptors inhibit brain activity and regulate sleep.

If clarithromycin is found to affect GABA receptors, researchers will have evidence to support a theory that hypersomnia and type 2 narcolepsy are caused by the production of a substance in patients’ nervous systems that acts like a sleeping pill on the GABA receptors.

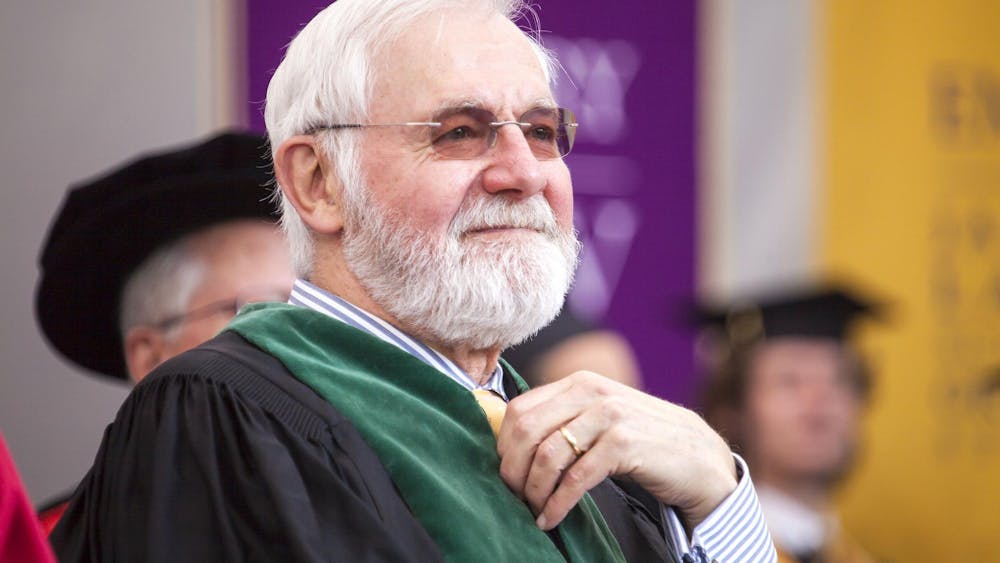

The theory was developed by the Director of Research for Emory Healthcare’s Program in Sleep Medicine David Rye, Division Chief for Anesthesiology Research Andrew Jenkins and former School of Nursing Professor Kathy Parker.