This past fall, the University, under the leadership of its new President Gregory L. Fenves, formalized a Task Force on Untold Stories and Disenfranchised Populations. The task force was created after the discovery of racist images in Emory yearbooks in 2019 and its work became even more urgent given the national discussions of racist brutality in the U.S. that has occurred since. The charge of this task force, according to a campus-wide announcement, is to honor the labor of enslaved persons, develop criteria for awarding scholarships, acknowledge the contributions of Indigenous peoples and develop educational and experiential opportunities. All these goals are laudable and easily within reach, and they should be implemented in concrete ways as soon as possible.

As I retire from Emory University this year, however, it is my hope that these beginning demonstrations of good faith will turn into something much more long-term than the many task forces and committees that have already come and gone, failed to produce material results and lacked significant follow-up. To be specific, I hope that the charge that the president has presented us with will, immediately, turn to a commitment to our own city, Atlanta.

As a professor who has taught a good many years here, it seems to me Emory does a much better job recruiting students from all over the globe than from our own city and that our classrooms do not, even remotely, represent the demographics of the very city we are located in, especially in relation to African American students from Atlanta. We need to recognize the responsibility we have to the place where we study and work. I find it extremely difficult to talk to professors and administrators about these matters. I hear that I am not acknowledging the work that Emory is already doing, not recognizing specific offices that explore community liaisons, not aware of scholarships already in place — basically, what I hear people telling me is that I need to do my homework. I feel, however, what I need is for people to listen to what I am saying. If a student comes from an Atlanta neighborhood where no one, or very few people, have ever gone to Emory, what are the chances that student will end up in an Emory classroom? If a potential student hasn’t graduated from high school, how will an Emory scholarship be of any use? If a person is incarcerated in one of Atlanta’s many jails and prisons, some of which I teach in myself, how can that person take classes at Emory?

Emory needs a bridge program that allows Atlanta residents who would never have the opportunity to attend a university anywhere to be guaranteed a slot at Emory upon successful completion of the program so that at some point in our not too distant future we can look across our classrooms and incorporate the viewpoints and experiences of people who grew up in the city where we are located. This cannot be accomplished by establishing more scholarships and creating memorials and doing a better job at unpacking our problematic history and renaming buildings; it can only come to pass by paying attention to who is inside the buildings. Every problematic name and history on campus can be reimagined, renamed, and re-memorialized, while the people inside the buildings remain the same. In our case, the people NOT inside our buildings will remain the same, the lack of a significant contingent of residents of our own city, even though we have people from everywhere else across the globe.

A bridge program is not some kind of quixotic dream beyond the ability of human knowledge; many different kinds of colleges and universities have these programs that could provide models. It could begin with Emory trying to explore ways of understanding that there are far more important realities than Emory’s yearly rankings in slick periodicals. We would be a better institution if we slipped in the rankings but took our classes to our closest neighbors. I was hoping, many years ago, when Emory was in a national scandal over accusations of misrepresenting its own data in order to achieve higher rankings, that we might have learned something. Instead, the University seems to keep pursuing these empty laurels like a hellhound on a death trail. Let’s find new priorities — how to build relations with the very people who live here and make a bridge program possible.

We are in an unprecedented time when change, at the university level, is no longer a possibility but an inevitability. Perhaps one of the greatest dangers of the pandemic is that technology will shift while our ethics remain the same or become further eroded than they already are. We are facing a new frontier in which teaching technologies could become a means of changing universities like ours into something different than simply a privileged space for ensuring that elites remain elite. There is no reason why classes cannot be opened to local people, especially disenfranchised people, who have not had the opportunity to take them before, and why programs cannot be developed for preparing them for success in such courses.

I've taught Native American Studies for three decades all over the U.S. and Canada, and the first thing I have tried to do at each institution when I arrived was to design courses whose content reflected the tribes in the immediate area of my new home. I think turning to the local population is a good model in order to have any understanding of the relationship between the past and the present. I would like us to consider that age-old gospel question: "Who is my neighbor?" This is a better question than “What is my ranking?”

To argue that such efforts would drag us down as an institution (besides being potentially racist) is like the educational equivalent of climate deniers who say that if we just keep supporting the coal industry everything will be OK. Other universities in our city, like Morehouse College, have started programs that give faculty credit for teaching in prisons. The beginning of these kinds of exchanges is truly exciting, and it won’t be long until colleges and universities in our city, as well as our nation, will surpass us if we only worry about scholarships, memorials, history rewrites, names on buildings and so on. These important efforts are beginnings, not endings. I hope we think of them as a down payment on establishing a profound connection to the city where our University is located.

I like to think about the kind of transformative powerhouse Emory might become if it had programs inside local jails, if Atlanta neighborhoods saw their first residents enrolled in our classes, if people who began a bridge program without high school diplomas ended up walking across our graduation stage. That’s when courageous inquiry would become more than a motto, and we could address systemic racism with something more than cosmetic treatments.

Craig Womack is the Associate Professor of English at Emory University.

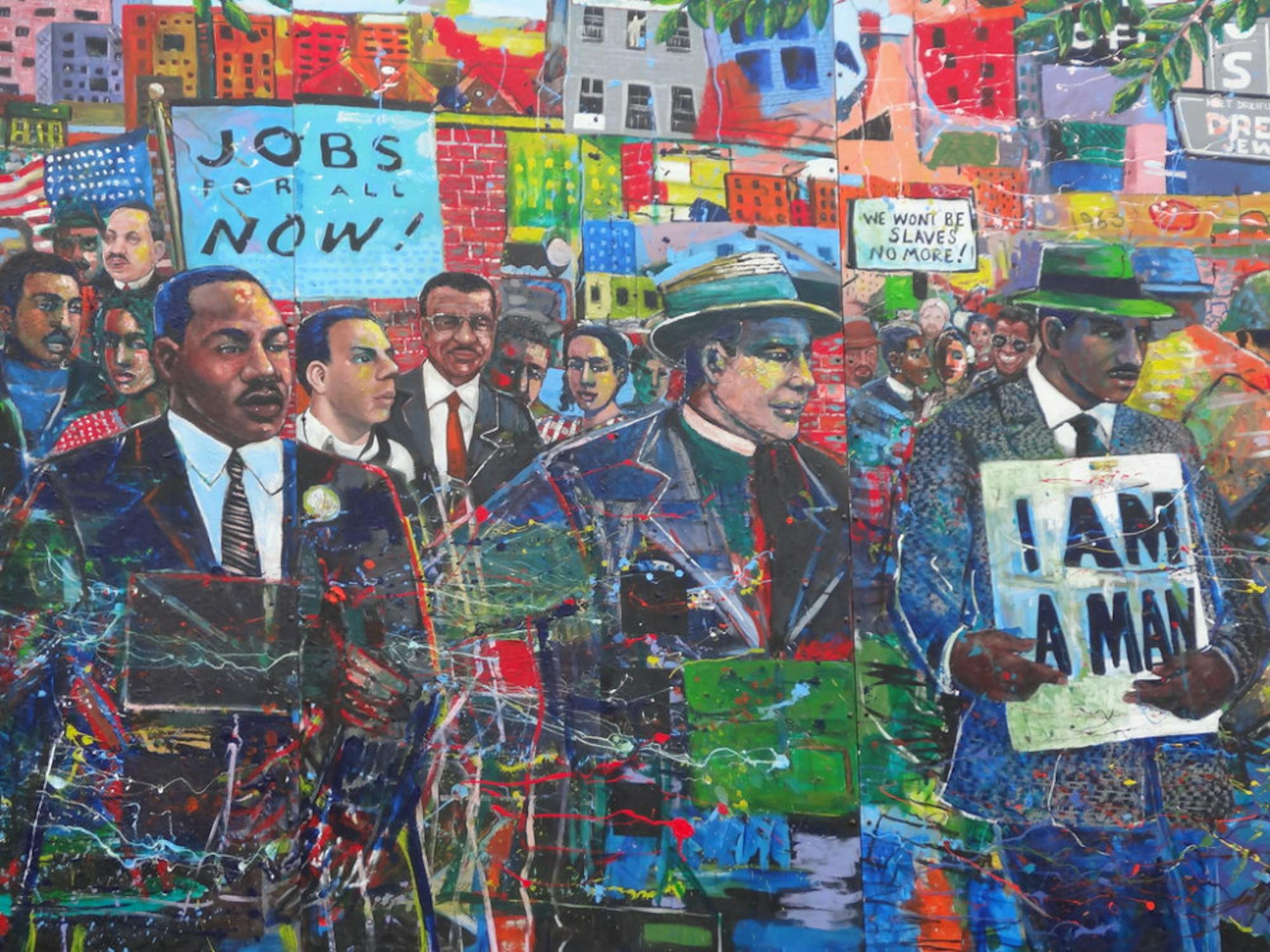

This article is one part of “1963,” an investigative opinion project. Read the rest here.