What would it look like for Emory University to align more ethically and transparently with respect to its past and present relationships with the Muscogee Creek Nation and Muscogee Creek people, and with respect to the contemporary realities of Native American people and nations in the United States today?

Why does this matter? And who does the work?

There are 573 federally recognized Indian Nations in the United States. Native Americans are approximately 2 percent of the national population. Across the U.S., Native American nations, intellectuals, artists and youth have been guiding lights for thinking in fresh and powerful ways about our relations to each other, the planet, food systems, health and wellness and the power of story. At the same time, there are pressing, urgent needs in Native American communities for greater access to better education, health care, environmental protections and so much more, to support the possibilities of viable, just and meaningful futures.

There is a deafening silence at Emory. There is limited inclusion of Native American voices and issues in the curriculum. Limited representation among our otherwise quite diverse faculty, staff and student body. No recognition of the land that we live and work on. Little to no mention of Indigenous Peoples Day (October 14th this year). And little to no programming for Native American Heritage Month (November). It should not fall upon a tiny and already overburdened minority of Native American faculty and students to be the front-line advocates for changes that might bring greater ethical alignment and fundamental knowledge in these areas.

At Emory University we are on land that is the ancestral homeland of the Muscogee (Creek), also spelled Mvskoke (Creek). Emory was founded in 1836, during a period of sustained oppression, land dispossession and forced removals of Mvskoke (Creek) and Ani’yunwi’ya (Cherokee) nations and peoples from Georgia and the Southeast. Dramatic encroachment on Indigenous land and rights had been ongoing since European settlement. In the 1820s, Mvskoke (Creek) were dispossessed of their land in the state of Georgia through coerced and fraudulent treaties. During this time, they relocated to Oklahoma, Arkansas and Alabama. In 1836, the Mvskoke (Creek) who had remained in Alabama were forcibly removed westward to present day Oklahoma by the U.S. government. The present-day Muscogee (Creek) Nation in Oklahoma is the fourth largest tribal nation in the U.S. with over 86,000 citizens.

This history is little known at Emory. Many universities in both the U.S. and Canada have land acknowledgement statements that are read at the start of important events. They also appear on websites and campus signage. Here is one example: "[I/We/Indiana University] wish/es to acknowledge and honor the Miami, Delaware, Potawatomi, and Shawnee people, on whose ancestral homelands and resources Indiana University was built" (The First Nations Educational & Cultural Center).

Anyone can make a land acknowledgement statement at any time. Official land acknowledgement statements can be viewed as empty and formulaic if they are not connected in meaningful ways to resources and other actions.

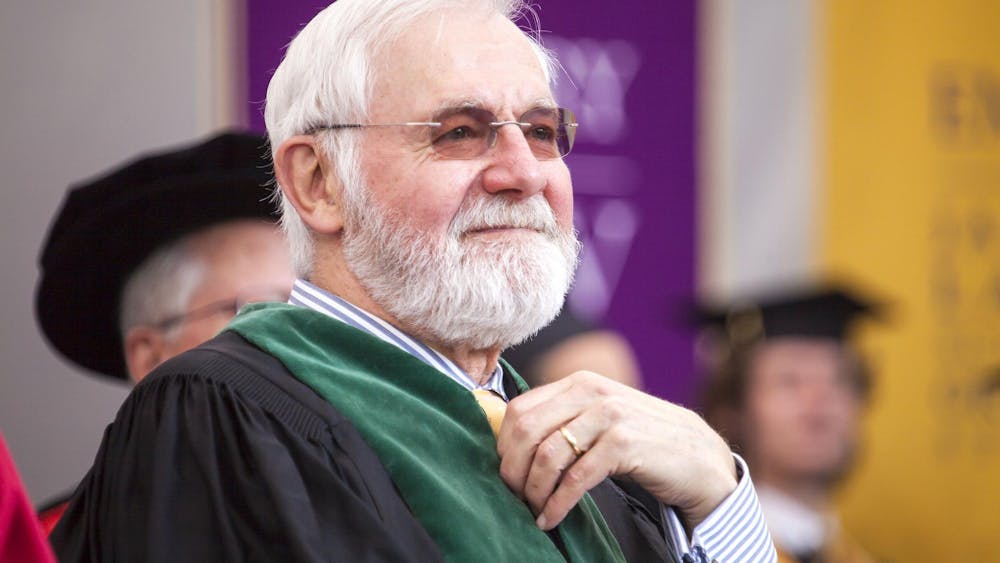

So what is more meaningful? Over the past five years we, and other Emory faculty, as well as Emory staff and students, have raised concerns with the leadership at Emory University. We have asked for increases in Native American faculty, staff and students; dedicated resources for scholarly programming in Native American studies; a land acknowledgement statement and stronger intellectual, cultural and educational links to Muscogee Creek institutions and individuals. Emory's Office of Undergraduate Admission is starting to make headway with undergraduate recruitment, and hosted a far-reaching symposium to explore these various issues in Fall 2018. Beyond Dean of Admission John Latting's office, direct and visible changes have yet to occur.

What is next? We invite President Claire E. Sterk to directly take this issue on as a moral mandate before leaving office: to remedy the glaring absence of Native American faculty, programming and connections to Muscogee Creek people. Dedicating resources for a cluster hire in Native faculty in areas of public health, religion, law, history and literature would be an effective way to begin. In addition, we hope that each person reading this open letter can call upon themselves and our leadership to work for greater representation, inclusion and alignment with Native American peoples, nations and interests. The remedies can begin today.

This letter was written by Associate Professor of Anthropology Debra Vidali; Associate Professor of English Craig Womack; English Lecturer and Emory Writing Center Director Mandy Suhr-Sytsma; Senior Lecturer of French and Italian Christine Ristaino; and Assistant Professor of Art History and Michael. C. Carlos Museum Faculty Curator Megan E. O’Neil.