The Election Integrity Act of 2021, also known as SB 202, was adopted by the Georgia General Assembly and signed by Gov. Brian Kemp in March 2021. The bill instituted numerous changes relating to voter eligibility, voter registration and election processes.

The 2022 midterms are the first election cycle since SB 202 was enacted, which was deemed an “anti-voter law” by protestors and an “election integrity” protector by supporters.

Changes under SB 202

Adam Byrnes (21Ox, 23C), a political science major, conducted research on changes implemented under SB 202 alongside Lauren Huiet (21Ox, 23B). According to Byrnes, a major part of the bill was the centralization of state authority, manifested in the alteration of the powers of the secretary of state, the State Elections Board and the General Assembly.

Under SB 202, the General Assembly — composed of the House of Representatives and the Senate — will now appoint the head of the State Election Board, a position that was previously filled by an elected secretary of state.

The change is listed in section five of the bill, stating that a majority vote in each chamber of the General Assembly is sufficient to fill the position. The chairperson is barred from participating in partisan political activities — including campaign contributions or participation in political party organizations — during their time as a chair, as well as in their two years prior to appointment.

“My concern is what happens if, at the county level, you have bad actors who want to disqualify voters for partisan reasons,” Byrnes said. “I think it went too far in terms of centralizing state authority and creating more avenues for bad actors if they get power to make a negative difference.”

Co-Communications Director of Young Democrats of Emory Virginia Brown (23C) also expressed concerns about the shift from an elected to an appointed position, saying it will allow the state legislature to take over and turn it into a partisan role.

“The chair of the Elections Board is appointed by the majority of the House and Senate, so in effect [it’s] going to be a Republican nominee, whereas the Secretary of State is directly nominated,” Brown said.

SB 202 also banned mobile polling units, which are RV-sized buses large enough to house eight to 10 voting stations. Under the bill, Fulton County will only be able to use mobile voting units during a declared disaster.

Nichola Hines, the president of the League of Women Voters of Atlanta-Fulton County — a nonpartisan, nonprofit organization dedicated to informing and educating voters — noted that SB 202’s ban on mobile voting units “stripped away” citizens’ ability to vote early.

During the pandemic in June 2020, Hines described a “debacle of primaries,” which the county decided to circumvent by booking large venues and building mobile units to increase voting access. Fulton County was the only county in Georgia to utilize mobile voting units, which created a “simple, secure” voting experience for voters of all ages and disabilities.

“Other counties were actually looking at this and saying, ‘This is a great idea, this is access to more people,” Hines said. “Fulton County was the only one who was thinking outside of the box — how can more people access the polls, less lines?”

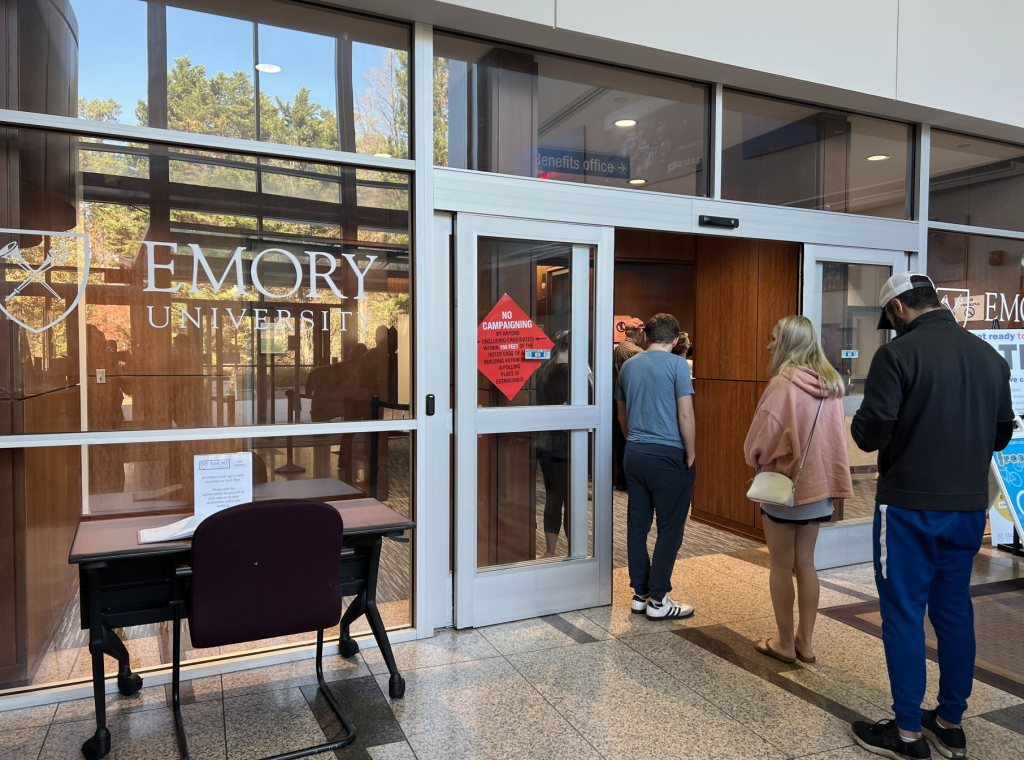

Emory community members line up for the last day of early voting at the 1599 Clifton Road polling station. (Matthew Chupack/Executive Editor)

When Hines used the mobile unit, she discovered that it was almost identical to walking to a regular precinct. The mobile voting unit had multiple polling units, with a poll supervisor and multiple poll workers.

According to Hines, the buses traveled throughout Fulton County on Saturdays and Sundays, spanning from North Fulton all the way to South Fulton. Additionally, people could easily access listings of the 24 scheduled bus stops.

Many of the bus stops reached isolated areas, where polling places may have been inconvenient. Hines added that, even as a resident of Atlanta, she isn’t able to walk to her county polling location.

“Go back to the name,” Hines said. “What does it have to do with integrity? The machines are the same machines, the workers are the same type of workers. Just now, instead of it being in a stationary building, they brought the machines to the voters.”

SB 202’s changes swing both ways, Byrnes added.

“This strikes me as a combination of fairly common sense smaller changes and more overbearing regulations that I don’t see a compelling need for, in terms of protecting election security,” Byrnes said.

Byrnes said that some of the changes outlined in the bill were understandable, such as IDs being required for absentee ballots. He said that the new rule — and the ability to use social security numbers instead of IDs — makes sense because IDs are required at polls.

However, Brown noted that Young Democrats of Emory faced challenges with the new requirement of including a photocopy of government ID, front and back, during registration. As the organization helped register students to vote, they had to make sure that the form was filled out correctly, print out the ID photos, match the photos with their registration and send them out.

“It was kind of a tedious process,” Brown said. “Although it was something we were able to do, it disenfranchises a lot of Black and Latino voters, or older, immunocompromised, disabled or low income people who don’t have access to printers.”

The bill also limited the number of days people can apply for an absentee ballot from 180 days to 78 days before an election. Absentee ballots could previously be requested up until the Friday before Election Day, but are now cut off 11 days before the election.

Additionally, there is a new limit of one absentee ballot drop box per 100,000 registered voters in each county, and the drop boxes must be indoors under surveillance. The boxes, which were previously outside under video surveillance and accessible 24 hours a day, are now limited to early voting hours.

Under SB 2020, Fulton County’s number of dropboxes fell from 38 to eight. Hines added that all other major counties were limited to five dropboxes.

“I had to find a parking spot for my car, get out of my car, then go in the building and drop it off, instead of having somewhere where it was accessible for me to stay in a car or just quickly park, drop and go,” Hines said.

She added that the drop boxes help people who don’t have time to go into a building to vote.

“If counties want to establish more dropboxes that are within state regulations … in a building, secure, with regulations on who guards and interacts with it, if they want to incur that cost, why can’t they?” Byrnes said.

Additionally, SB 202’s new voter challenge provision states that any individual voter can submit an unlimited number of challenges to the eligibility of voters. At the county level, Byrnes said that there might be “bad actors” who seek to disqualify voters for partisan reasons.

“This is kind of just a net negative, as a bill,” Brown said. “One of the fundamental principles of being in a democracy is that every person has the right to vote, and this is just undermining that.”

However, Brown noted that she believes there are parts of the bill that help promote fair elections. Under the bill, poll workers who reside in different counties are allowed to work in metropolitan areas, meaning Georgians from rural areas will be able to help run elections elsewhere.

This year’s midterms

Redistricting, the redrawing of new congressional and state legislative district boundaries, occurs every ten years. Kemp signed Georgia’s congressional map into law in December 2021, removing Democratic precincts in DeKalb County from Georgia’s sixth congressional district and adding in more conservative counties.

According to Georgia Public Broadcasting, the new boundaries are likely to elect nine Republicans and five Democrats, compared to the eight Republicans and six Democrats elected in 2020.

“You want to make sure, because of new-drawn lines, that you’re polling in the right place, you know who you’re voting for,” Hines said. “Your state senator, representative, even your commissioners could have changes. You want to make sure before you get in there that you’re not shocked.”

Hines introduced the idea of “sexy candidates,” such as the senator, governor and secretary of state, who make people more “excited” to vote due to greater knowledge about the candidates. However, one of her organization’s goals is to inform people about the candidates further down the ballot.

For example, the state superintendent — the elected officer of the State Board of Education — can’t necessarily write legislation, but they still have considerable influence on the legislators who write bills. More recently, the “Protect Students First Act” requiring school administrators to limit how race can be discussed in the classroom was passed in April 2022, along with other proposed bills to censor classroom conversations and strip funding from Georgia students.

Another important position is the labor commissioner of the Department of Labor, which showed its “antiquated” infrastructure during the 2020 pandemic, according to Hines. She said that, as thousands of people were laid off from their jobs, some Georgians weren’t able to receive checks and other necessities due to lack of a system in place.

“The lower the candidates are on the ballot, the closer they are to everyday life,” Hines said. “We’re stressing to fold to pay attention, don’t just vote for those top two.”

Brown noted that SB 202 is making it harder for most people who traditionally vote Democrat to register to vote. Black, Hispanic and Asian individuals, as well as lower-income individuals, who lean Democrat, overwhelmingly vote blue.

Georgia lawmakers were hit with several lawsuits in 2021 alleging that SB 202 disproportionately harmed voters of color as a means to achieve a partisan end. Both the Lawyer’s Committee for Civil Rights Under Law and the Legal Defense Fund filed lawsuits in March 2021 against Georgia Secretary of State Brad Raffensperger and the Georgia State Election Board on grounds of racial discrimination against voters.

The Lawyer’s Committee’s lawsuit alleges that race was a “motivating factor” behind SB 202.

“SB 202 was enacted at a time when Black voters and other voters of color were making increasing use of means of voting,” the lawsuit states. “SB 202 was enacted immediately following elections in which the size of the population of Black voters and other voters of color, particularly when compared to the diminishing share of the white vote, had become larger in statewide elections.”

The Legal Defense Fund’s lawsuit also lists Kemp as a defendant.

“Specifically, SB 202 interacts with historical, socioeconomic, and other electoral conditions in Georgia to prevent voters of color, and particularly Black voters, from having an equal opportunity to participate in the political process on account of their race or color,” the lawsuit reads.

Three months later, the U.S. Justice Department filed a lawsuit against the state of Georgia, Raffesperger and the Georgia State Election Board for on the grounds that “the cumulative and discriminatory effect of these laws — particularly on Black voters — was known to lawmakers and that lawmakers adopted the law despite this.”

However, Brown doesn’t think that it will depress turnout, because people “see how important it is” to vote.

“They see that there’s people trying to actively take away their ability to vote, and they’re trying to counteract that,” Brown said. “That’s something we’ve been trying to do as an organization, to make sure these changes don’t affect how many people are able to turn out.”

Byrnes also said anger at the bill’s passage might incentivize people to turn out to vote. Georgia voters set an all-time high during early voting, with turnout concluding at 2,288,889 voters casting their ballot by the end of last Friday.

Additionally, Byrnes doesn’t think the bill will impact the 2022 midterms elections as much as it might alter future events, expressing concerns with the provisions outlined in the bill “being in the hands of bad actors.”

“What if people get in the State Election Board who want to take over county election boards and replace supervisors they don’t like, for political reasons?” Byrnes said.

Emory College Republicans Chairman Robert Schmad (23C) and Vice President Paul O’Friel (23C) did not respond for comment by press time. Professor of Sociology and Emory College Republicans Faculty Advisor Frank Lechner declined to comment.

Ashley Zhu (she/her) (25C) is from Dallas, Texas, majoring in biology and minoring in sociology. She is the vice president of recruitment for the Residence Hall Association, a sophomore advisor for Raoul Hall and a staff writer for the Emory Undergraduate Medical Review. She is involved in cell biology research at the Pallas Lab and is a BIOL 141 Learning Assistant. Zhu enjoys FaceTiming her dog, stalking people's Spotify playlists and listening to classical music in her free time.